Grimshaw Partners Andrew Whalley and Neven Sidor reflect on Nick Grimshaw’s pragmatism and quirks, and recall conversations after “several hours and several rounds of scotch and dry ginger.”

Earlier this month Nick Grimshaw passed away at the age of 85. News was announced by his practice, Grimshaw, which he founded in 1980, who said in a statement he had been “a man of invention and ideas” and who would be remembered for “his endless curiosity about how things are made”.

Partners at Grimshaw Andrew Whalley and Neven Sidor shared their memories of working alongside Nick Grimshaw with AT.

Neven Sidor

The scotch and dry ginger conversations

Imagine the following scenario: It’s the end of a long day. There’s something unsaid that needs resolution. There’s only one cellular room in the studio and it’s Nick’s room, surrounded by glass with a bank of Herman Miller Action Office furniture along the back wall. Several of its lower drawers are generously stocked with scotch and dry ginger. You (or he) go in with a grievance but after several hours and several rounds of scotch and dry ginger you (or he) come out wondering what it had all been about. Was this deliberate obfuscation or just a natural response from a leader nervous of direct confrontation? It worked because alcohol and some protracted elliptical but absorbing conversation engendered sympathy in both directions.

The Daler-Rowney black books

Ever since a QC impressed on him the effectiveness of contemporaneous handwritten notes in forcing recalcitrant clients to pay unacknowledged fees, Nick recorded every meeting in his working life on a single page of an A4 Daler-Rowney unlined notebook. For as long as I can remember he used the same blue biro and recorded just the key points as he saw them in words and sketches, whether these points concerned design or just business. Each entry is meticulously ordered, searingly concise, and sometimes infuriatingly all- inclusive from the point of view of those of us that had just shared our own design sketches in the meeting.

Quirks

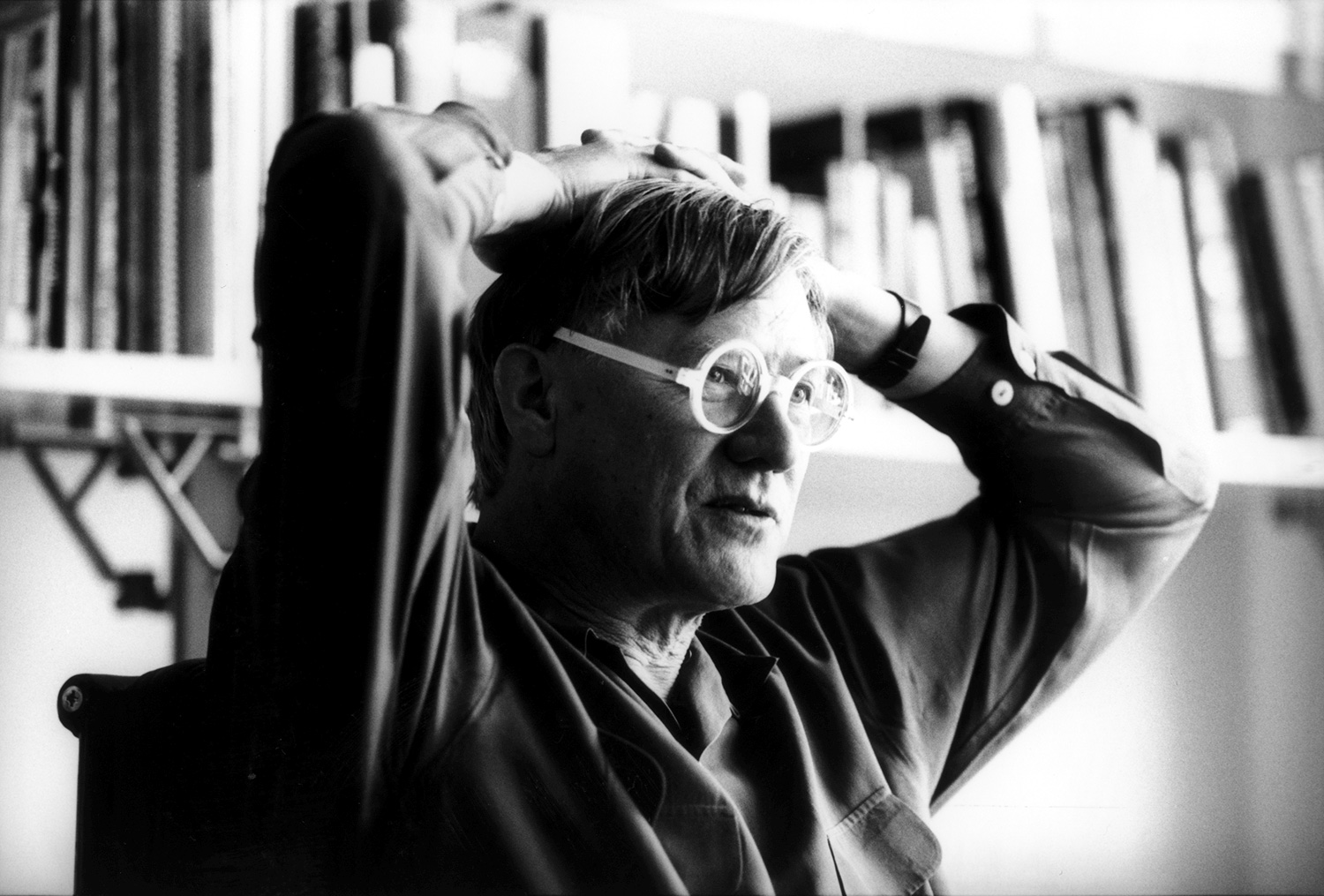

I knew what Nick looked like well before I first met him. With his Beatles haircut, Philip Johnson glasses, flared trousers and kipper tie he was probably the most cartoon-able British architect in the 70s. I remember going for a walk along Holkham beach with him and Lavinia when my five-year-old daughter pulled me down genuinely perplexed and whispered: “why does he wear those joke glasses”. While his philosophy was pragmatic and highly rational, one must also ask how exactly this sits with his boat/ship fetish. Why are there so many Daler-Rowney sketches with spines, ribs and keels? Why did Western Morning News need a prow? I suppose we all have our quirks and blind spots.

Succession

Having watched his practice grow from fourteen people in what was virtually a single room to five hundred plus in seven offices across three continents Nick must have been proud but also slightly perplexed. I remember a speech he gave at a Christmas party near the start when he tried to lift the mood by saying he looked forward to working with a smaller and tighter team in the New Year. Cheers! I too remember being perplexed when we crossed a threshold, and I didn’t know everyone’s name anymore. Having said that there is no doubt that Nick handled the thorny question of succession perfectly. The key to it was his taking his foot off the gas early enough, so that all the most talented and ambitious people unpacked their escape bags and stayed. It wasn’t a completely linear process. There were plenty of moments when he panicked and tightened the reins but trust generally returned.

Andrew Whalley

Working with Nick Grimshaw

With over four decades alongside Nick Grimshaw, I’ve witnessed firsthand his passion, ingenuity, and commitment to architecture. From the early founding days of the practice in 1980, through defining projects such as Waterloo International Terminal and the Eden Project in Cornwall, Nick’s restless curiosity and inventive spirit shaped not only our studio but the broader profession.

Beginnings

When I joined in the mid-1980s, the practice numbered just 12 architects. Amid a recession, industrial and sports commissions sustained us — and one landmark: the Sainsbury’s Superstore in Camden. Its articulated steel roof, suspended from cantilevered gerberettes, exemplified Nick’s approach: clarity of structure, expressive use of industrial technology, and invention born from constraint.

I still recall waiting in reception, studying the skeletal model, when Nick — in his translucent round spectacles and glass-walled office — invited me to leave my portfolio. There was no vacancy, but he later reviewed it, created a place, and invited me back. That decision began a working relationship and friendship that lasted 40 years.

Ingenuity and invention

Nick’s instinct was always to balance economy with ingenuity. At Herman Miller’s factories, pressed aluminium and fibreglass became living skins, adaptable over time. He worked directly with manufacturers, pushing industrial techniques into architecture. He was endlessly curious about how things were made — and tenacious in persuading others that daring ideas could be both practical and economical.

This pragmatism defined the 1980s. At Brentford’s Homebase store, a vast hall was supported by wing-like trusses, clad with ordinary aluminium sheets textured by a crimping machine. At the Financial Times printworks in Docklands, presses rolled behind a 96-metre glass wall — urban theatre born of industrial logic.

Culture and conviction

The practice was a meritocracy where ideas, not hierarchy, ruled. This reflected Nick’s personality — genial, open, collaborative. His background shaped him: son of an aircraft engineer and an artist, raised by creative women after his father’s early death. At the Architectural Association, tutored by Archigram, he produced an animated, modular reimagining of Covent Garden — decades ahead of its time. His early Service Tower in Paddington, with prefabricated pods spiralling around a core, was both sculpture and manifesto for adaptive reuse.

Waterloo and beyond

By the late 1980s, Grimshaw was grouped with Foster, Rogers, and Hopkins as the “High-Tech Four.” But Nick’s inspiration came more from Prouvé, Paxton, and Brunel: pragmatic, inventive, humane.

The breakthrough was Waterloo International Terminal, won in 1988. With no CAD, Nick bet instead on Apple desktops — eccentric at the time, but decisive. Built in just 36 months, its vast curving roof fused structure and architecture in one. Norman Foster later remarked: “In Nick’s outstanding work, the structure becomes the architecture.” Waterloo won the RIBA Building of the Year and Mies van der Rohe Prize, and it remained Nick’s favourite building.

At the same time, the British Pavilion for Seville Expo ’92 pioneered photovoltaic panels, cascading water walls, and passive cooling — one of the first major projects to integrate renewable energy and climate-responsive design. It set the course for what became a lifelong exploration of sustainability.

Eden and legacy.

Of all the millennium projects we worked on, which included Thermae Bath Spa and the National Space Centre in Leicester, The Eden Project, completed in 2001, looked the least likely. But its design, a series of interlocking geodesic domes that like soap bubbles could easily adapt to the contours of the site, became not only an international landmark but a catalyst for regional economic revival.

Nick was knighted in 2002 and served as President of the Royal Academy from 2004-2011. He restructured Grimshaw as an LLP in 2007, ensuring succession and opening ownership to new generations. In 2019, he received the RIBA Royal Gold Medal. His final act of generosity was the Grimshaw Foundation, dedicated to supporting under-represented young people into creative careers.

Beauty through ingenuity

From the Service Tower in 1967 to the Elizabeth Line in 2022, Nick’s buildings fused pragmatism with imagination, economy with elegance, invention with joy. His enduring legacy is a practice — and a profession — animated by his belief in beauty through ingenuity.