Project 3’s renovation of Lower Campfield Market in Castlefield, Manchester, marks a new chapter for a structure that has adapted to the city’s social and economic tides.

From pasture to market, museum to wartime balloon factory and back again, the Grade II-listed Lower Campfield Market – now rebranded simply as Campfield – is embarking on a new chapter, as a hub for technology and creativity. The once open-sided market hall has experienced a restless past, never quite settling into a single typology, programme or internal arrangement. Born of Victorian ideals of improvement and enterprise, the building has consistently mirrored Manchester’s shifting public priorities – a kind of civic barometer, continuously welcoming change and adapting to the social and economic tides of the city.

Situated in Castlefield, Manchester’s largest conservation area, Campfield forms part of Manchester’s historical civic core, alongside Roman ruins, red-brick warehouses and landmark contemporary interventions, such as OMA’s Aviva Studios and SimpsonHaugh’s Beetham Tower. Originally designed in 1876 by Magnall & Littlewoods, opposite the Museum of Science and Industry (previously Liverpool Road Station, the world’s first inter-city railway station in 1830), the structure is defined by its lofty cast and wrought iron frame, and an ornate slate, timber and glass roof. The space embodied a Victorian ambition for light, order and hygiene. However, within a year of completion, the hall had already been modified – its open flanks enclosed with timber panels, decorative iron railings, glazing and sliding iron gates. From the outset, this was a building designed to evolve.

Designed as an open-sided market hall in 1876, the building withstood many changes to its structure and use, but had stood empty since 2012.

By 2021, the building stood empty following the permanent closure of the Museum of Air and Space, a long-dormant satellite of the Museum of Science and Industry, which had shut its doors in 2012. What remained was a structurally compromised shell; architecturally distinctive but materially deteriorated, caught between heritage status, the inertia of vacancy, and a desperate need for significant repairs and investment. Recognising its potential as a strategic asset within the city centre, Manchester City Council secured £17.2m from the Levelling Up Fund to bring Campfield back to life. The funding, delivered on a time-limited basis, catalysed a partnership with building owners Manchester City Council and with Allied London’s workplace brand, Department, to regenerate the hall within the city’s new innovation and creative district, St John’s.

In an era where the built environment accounts for nearly 40 per cent of global carbon emissions, adaptive reuse is no longer simply a matter of preservation – it is a critical climate strategy. Retaining and reimagining an existing structure offers both embodied carbon savings and cultural continuity, layering histories whilst simultaneously grounding future interventions in material memory.

Private meeting rooms are housed in OSB-clad boxes at the edge of the mezzanine.

How, then, do architects and designers strike the delicate balance between preservation and transformation? How can heritage buildings be adapted not only for present-day social, cultural and economic needs, but with the resilience to accommodate future change? What does it mean to retain the spirit of a structure while unlocking its potential for reinvention? These are the questions at the heart of Campfield’s renewal. The challenge, which has spanned centuries now, is in finding the right typology for the space – one that reflects the responsive nature of the structure itself, and allows for flexibility and reprogramming over time.

Allied London brought forward a vision of the revitalised civic asset – a largely untested mixed-use typology pairing start-up offices and workspaces with a publicly-accessible restaurant and bar. Project 3 Architects was tasked with delivering the project, working within the tight constraints of a Grade II-listed building embedded in a high-profile conservation area, public funding expiration deadlines, and the unpredictable conditions that come with adapting old fabric for contemporary use. Co-director of Project 3 Architects, Andrew Bamford’s response to the challenge was that “reinvention was necessary, but the method of reinvention was to allow the building to celebrate and retain its grandeur.”

Designed to be removable and demountable, the free-standing mezzanine is entirely independent of the existing structure, ensuring minimal impact on the listed building, while preserving the spatial drama of the interior.

There had been piecemeal attempts to repair the space over the years. A new roof had been installed after structural deterioration had rendered the roof too weak to hold the weight of the original slate. As a response to the structural recommendations in the 1980s, around 3,500 square metres of asbestos was installed, as well as corrugated plastic sheeting over the glass roof, resulting in mould growth and several broken panes. Due to these significant challenges, the project was delivered in two key phases. The first phase addressed the roof; removing broken panes of glass – which instantly allowed light to flood into the space – and celebrating the ornate iron columns and roof structure which were surprisingly still intact. The second phase focused on the renovation of the internal space with an approach characterised by Bamford as intentionally “light-touch and subservient to the building and its history.”

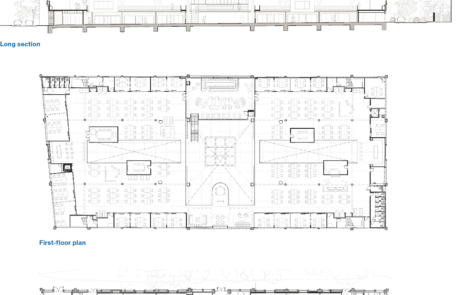

There is a clear hierarchy with regards to the layout of spaces. At the heart of the scheme lie the restaurant, bar and event space, all of which enjoy unrestricted views of the roof and cast iron structure. The publicly-accessible areas, although making up a smaller proportion of the scheme, appear the most celebrated due to the height of the space and its abundance of natural daylight. The multi-use space is inclusive of full-height fire and acoustic curtains to create a fully enclosed area which allows for a number of activities to happen concurrently alongside the office space.

The design celebrates the Victorian cast and wrought iron frame and ornate roof.

On the ground floor, symmetrically off the central space and hidden under the shadow of the mezzanine, lie the larger office spaces, beautifully clad in reused timber from the building’s original mezzanine. Each internal window head incrementally steps down by 600mm towards Lower Byrom Street, where the waste historically drained to.

Each of these spaces are linked via Green Street, the arterial vein running through the centre of the scheme which gives the office its own ‘garden’ space decorated with planting and furniture for spontaneous and chance encounters with neighbours. The plant-lined walkway contains many areas for casual workplace conversations and gives a nod to wider themes of connection and engagement, referencing not only the former street market but also the civic and social role that the building has long performed. Green Street has the potential to transform the idea of the workplace, reframing it as a space that fosters gathering, community and collaboration, whilst still remaining a flexible and dynamic space.

Upstairs, smaller, cellular office spaces are pushed to the edges of the building, with a number of private meeting rooms lining the edge of the mezzanine, all of which are OSB-clad – a compromise in relation to the interior design – alongside mesh infill to avoid obstructing views of the overall volume. The remaining space on the mezzanine is predominately given to open-plan co-working space with unobstructed views of the existing cast iron columns that separate the space into different zones. Colour is generally well controlled within the project, using a limited colour palette. Service areas, such as kitchenettes, changing rooms and WCs, are brightly coloured to provide moments of joy within spaces that are often mundane.

A double-height multi-use space at the centre of the plan accommodates informal working or large-scale events.

The project’s tour de force lies in its technical ingenuity – reviving the building in a way that is durable but inherently adaptable. Designing a scheme to be removable and demountable within a listed structure is no small feat. The mezzanine structure itself is free-standing and does not connect to the external fabric in any way. Nor, in fact, do any of the new elements of the design, ensuring minimal impact on the existing building, whilst preserving the spatial drama of the interior.

The team came up with a number of innovative strategies to tackle the array of challenges relating to services, acoustics and fire. All of the services – hidden away on the cellular offices’ roof spaces – are fixed with lightweight gripple fixings to avoid mechanical fixing and additional weight to the listed fabric, a move that reinforces the vast volume of space that the building uniquely provides. The MEP strategy replicates the footprint of the historic fittings, such as the ventilation ducting following the old gas heater routes, and old pendant lights replaced with modern energy-efficient equivalents. The flexibility of the office spaces – partitions between the cellular offices can be demounted to allow for company expansions – has also been factored into the MEP design.

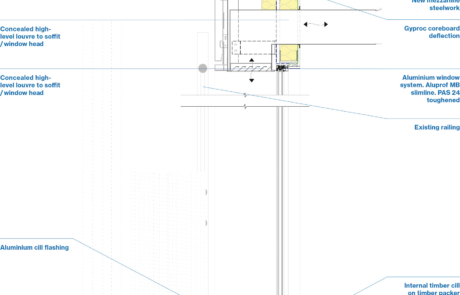

Concealed windows are hidden behind portions of the restored historic façade.

The scheme prioritises natural light for the majority of users although, inevitably, there is a notable difference in the quality of daylight in the ground-floor offices and the open-plan areas, which are drenched in natural daylight. The fenestration and accompanying MEP design within the office spaces are noteworthy, due to the listed building constraint, whereby the design cannot physically alter the external fabric or bear any load onto the external façade. The design cleverly places a concealed high-level louvred ventilation system externally at the top of the window forming the soffit, behind an aluminium cladding system – all of which is installed internally, behind the listed railing system.

Working with adaptive reuse requires reverence, adaptability, and a flexible mindset. It often calls for creative solutions, design innovation, and radical thinking. Campfield demonstrates that, despite complex constraints and listed building conditions, it is possible to deliver a toolkit of responsive interventions, merging restoration with long-term flexibility. The result is a scheme that not only protects the building’s heritage, but also makes future change relatively effortless. Its design—non- invasive, flexible, impermanent, and able to accommodate up to 600 people – positions heritage not as an obstacle but as an active framework for future use. The project is technically rigorous and socially generous. By layering programmes within the building’s vast volumes, it transforms ad-hoc meetings and fleeting social encounters into new cultural rituals in once silent halls – moments that aim to deepen local pride and keep the historic fabric alive for a collective convergence of creativity.

Flexibility is paramount in any adaptive reuse scheme. Though it brings challenges, those constraints often become creative springboards – opportunities to learn, reimagine, and rethink. Campfield shows that true flexibility goes beyond spatial planning; it is a mindset. The internal fit-out narrates a story of impermanence layered over an enduring backdrop – the Grade II-listed fabric – clearing the way for the future chapters in the building’s architectural journey.

Credits

Client

Manchester City Council / Allied London

Architect

Project 3 Architects

Project manager

OBI

Heritage architect

Stephen Levrant Heritage Architecture

Structural & civil engineer

Civic

Interior designer

Sheila Bird / Hart

Mechanical and electrical design

MEP

Quantity surveyor

MAC

Planning consultant

Zerum

Acoustic design

Sandy Brown

Fire engineer

Jensen Hughes

Main Contractor

Amspec