Patel Taylor has designed 8-13 Casson Square, a residential tower at Southbank Place in Waterloo. Practice co-founder Pankaj Patel talks to client Guy Dare about Squire and Partner’s masterplan, crafted elevations and transforming one of London’s most prominent riverside sites into a high-density mixed-use neighbourhood and a desirable place to live.

Photos

Peter Cook and Jack Hobhouse

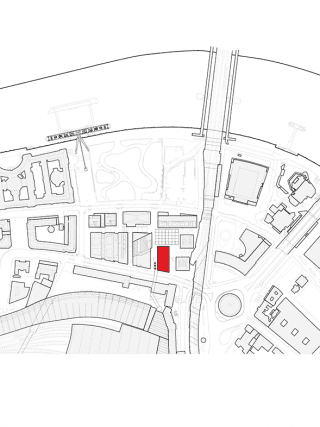

Guy Dare Southbank Place was a joint venture between Canary Wharf Group and Qatari Diar. I was the design manager at Canary Wharf Group and the prime client representative, particularly at the inception and preplanning stage. We won the project through a competition tender process. It was a long-lease purchase of the land from Shell and, as part of that, the development of a new office campus for Shell and then mixed-use development for the remainder of the site.

It was an exceptional opportunity in the sense that the location is quite extraordinary when you consider that it’s diagonally across Westminster Bridge from Westminster. And there was this piece of land that was really just blowing in the wind. It was an important location for London, very close to the Thames and to the World Heritage Site of Westminster Square and the Houses of Parliament, so that created the aspiration for a world-class mixed-use development.

We very quickly understood both the limitations and the challenges of the site. There was an economic issue to be dealt with in terms of the cost of the land and what we needed to create in terms of value. But the fact that we were within views of the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Square informed the massing that we ended up with – or limited the massing opportunities that we had. We knew we wanted to work with world-class, primarily British, architects. We saw that as being quite important.

Pankaj Patel We were absolutely thrilled to be invited to the limited competition for the tower. We’d worked with Canary Wharf Group off and on, so we had a clear idea of their level of ambition and the quality they expect and the way they create a place. We knew this was a client with the vision to do groundbreaking schemes and to talk about things that maybe other clients wouldn’t: How to create the most amazing high-density residential living. How to mix different tenures to create a community. How to include social areas and sky gardens, so people can meet, which is an idea that is common in Singapore and other places but not so much in London.

In the meetings we had with Guy, we talked about creating an English template; about how to establish a model for high-density living in London. What would you do? How would it differ from Manhattan? They had a vision in the brief about turning an introverted site into an extroverted, permeable, mixed-use site.

Michael Squire’s masterplan is a fantastic diagram of legibility and clarity. Michael had a very clear idea about the block structure, the visual connection and the spatial connection. And that was what held that masterplan together and gave that formal quality.

There was a big debate about how to avoid having any traffic, which helped shape the public realm and actually works perfectly now that it’s built. We talked about the fact South Bank never had a front door, an entrance. So the idea was that this building would be the gateway for people; the point where they would say: “Now I’m in South Bank.”

A new gateway for South Bank. The ground floor is home to the western ticket hall and escalator access to Waterloo underground station.

Guy Dare Pankaj and I talked about the 15-minute neighbourhood – and now that’s becoming a cliché. But the reality is that actually South Bank Place is that neighbourhood. You can live, work, play and enjoy life all in that development. It has the right ingredients to sustain itself in that way. And that, in part, was due to the planning guidance we had. And then we’re very fortunate in the sense that we’ve got Jubilee Gardens in front of the development as an amenity as well.

Pankaj Patel Having people living there gives South Bank an added life through particular hours of the day, particularly in the evenings. Canary Wharf wanted to establish a community. We’ve got WeWork space, we’ve got residential and the mixed use, this huge basement with a pool, a supermarket – everything for local people. We’ve got an extra care facility in the building, which is totally unique for such a high-density scheme. Because of Covid, the housing association Notting Hill Genesis decided it had a greater need for doctors and nurses to be living closer to Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals. So it’s now been given over to them and it will go back to extra care when things change. So this idea of adaptability is quite important as well – that buildings can change.

We’ve got a mix of apartments from studios through to family units. I think the social diagram of the building – the corridors, the social spaces – will make it a nice place for people to create a home for a long time. And then, for us, there was this added interest about how to make complex tenures – from extra care to intermediate to private – come together and feel as if they’re part of this building. So the corridors culminate into these sky gardens, which are accessed on every third floor and that provide a social space where people interact.

External terraces afford panoramic views of the city.

Guy Dare There’s a multigenerational society in South Bank, just by virtue of the fact that some of the higher apartments are probably going to be occupied by younger people or professional people and then there’s the elderly care component as well. This means it will be a very exciting place for people to be. Those sky gardens will inevitably create opportunities for intergenerational socialising and mixing. Isn’t that what everybody’s looking at now? No one wants to be in a silo anymore.

Pankaj Patel There’s a question about how you make high-density developments along the river in London. It’s about opening up the site, but also relating to context. So at Casson Square we’ve got a tower with four different facades, all of which respond to their context. One makes reference to Shell, one to Michael Squire’s building, one to the KPF building, one with grand

sky gardens.

The bay windows, the mixed community, the sky gardens – these are all devices that make the high density work. And that helps to maximise the value of South Bank and the river and Jubilee Park.

Guy Dare I think the lynchpin of a lot of what we did there was the Shell Centre and also the Royal Festival Hall, which are both of the same period. Paul Williams from Stanton Williams would always refer to this string of pearls, this necklace of palazzos and buildings along the Thames. Part of the joy is seeing the richness that comes out of buildings from different generations, and also some of those buildings being reinvented over a period of time.

A genuine mission for us was to create something that has a timeless but long-lasting quality, which in part comes from the choice of materials we were obliged to use – limestone and bronze – which are taken from not only Shell, but also Regent Street. Look at any of the major arterial roots through London and you’ll see those materials. They are essentially London materials. High-rise is something that’s not necessarily British by origin, but I think we’ve given it a very British feel.

I think it has a timeless quality; the whole Shell development has a very timeless quality. So I don’t think you’ll be able to say that this is early 2000s architecture. It’s about complementing what’s gone before while laying the foundations for the future. I think we’ve done that. And it’s important to make high-quality dynamic buildings that will stand the test of time.

Pankaj Patel We had that question of how to deal with being in a conservation area. We wanted to make a highly crafted building, beautifully put together, as Canary Wharf always does. We used the idea of the external wall as the intermediary between the public realm and the private realm. We looked at English 19th-century architecture and the use of the bay window as a device to allow you to engage with the street. Oriel Chambers in Liverpool, designed by Peter Ellis and built in 1864, was an inspiration. That was where we started: the idea that every room has this amazing bay window to give each room a particular set of orientations and views but also a stature and presence so that people who inhabit those rooms will feel really special.

We were working to a strict deadline regarding the tube station ticket hall we were building at the lower levels, which had to be finished by 2018. That was a line in the sand they couldn’t change. That programme meant that we had to get it unitised. We started working with fabrication people, we did a lot of R&D. We wanted to go off-site to save time and money and to ensure the level of craftsmanship. Those drivers shaped the way the building looked, and how we procured it. It ended up being completely prefabricated apart from the core – every column, every slab.

The bay windows were made in Northern Ireland, then shipped to Sheffield with a precast concrete guide to put the window together. They were delivered in one piece on a huge truck. There was about 30 minutes to unload and three hours to plug it in and make it weather tight. The supply line was absolutely incredible.

Bay windows allow residents to ‘step outside’ the building envelope and enjoy triple aspect views.

Guy Dare We’ve always tried to deliver value, and the curtain wall is probably one of the most expensive elements of the building. But I think the kit-of-parts approach and the supply chain agreements we had with the cladding contractor helped create a construction-friendly facade that worked. There was that tension there between the architectural intent and what was physically possible. And we probably stretched both of those – as you should. The facades actually had to deal with some very significant constraints simply because we have streets running east/west towards the river, which meant that the daylight issues created some challenges for us as well.

Bay window studies showing different configurations of balconies and bay windows.

Pankaj Patel It was a real challenge to work out how to get daylight through because the buildings are 13.5 metres apart. But the quality of light was crucial to our brief. That drove the design of the bay windows; where they stop and where they start. As you go higher up, the piers get more elaborate and get carved and tooled to be more filigree. So you actually get more glass as you go up, and the larger planes of glass then capture the big skyline.

All our clients are asking about the impact of Covid. People want bigger rooms or a study. What they’re not questioning is the quality of the rooms you’ve got. Having a little bit of extra space in a room, where you can put another piece of furniture or step out beyond the rectangle of the room, has a huge impact on the lived experience of somebody spending time in that space. The amount of glazing makes it a fantastic experience to be in these rooms. There is ample light coming through. And the bay window means you can sit at a desk or in an armchair and look along the river, see the skyline. You get this wonderful aspect and it changes your mood. I think that’s quite important.

We wouldn’t be able to do it now. The new legislation says that the maximum amount of glass should be 30% of the external wall. The driver in terms of energy efficiency is absolutely spot on. But that means that 70% of the wall is completely blind. The human condition likes light and space and views, whether they’re reading a book, or writing a report, or thinking or resting. There should be a sense of delight in being in occupying a room. In this building that’s done by the fifth wall, the carved-out elevation with the balconies and bay windows. Why can’t we do what Scandinavians do? Use triple glazing. As simple as that.

Ground floor apertures are scaled to bring a heroic scale to the new civic space.

Guy Dare I think the glazing was a necessity to make this habitable. I think the 30/70 split may well be appropriate in some locations, but not necessarily all of them.

If you’re in a greenfield site, 30/70 probably works. I think it has to be done on a case-by-case basis. And that’s what the best architecture does; it addresses the context.

The new high-rise buildings reference the proportions and materials of the adjacent Shell building. The aim was to create a timeless development with the density of Manhattan, but a very British feel.

Download Drawings

Credits

Architect and lead consultant

Patel Taylor

Client

Canary Wharf Group and Qatari Diar

Structural engineer

WSP

MEP engineer

Hoare Lea

Facade consultant

Thornton Tomasetti

Interior architect

Darling Associates

Fire consultant

AECOM

Construction manager and Quantity surveyor

Canary Wharf Contractors

Glazing contractor

McMullen

Precast concrete

Explore

MEP

Kane

Stone/tiling

Stone & Ceramic

Kitchens

CIE

Vertical transportation

Schindler