In an excerpt from a new collection of essays in honour of Kenneth Frampton, Mary McLeod recounts the emergence of a ‘critical’ position in the historian’s work

Published by Thames & Hudson, ‘Architecture and the Life World: Essays in Honour of Kenneth Frampton’ is a celebration of the distinguished historian’s career and thinking. Edited by Karla Cavarra Britton and Robert McCarter, the book (352pp, £45) features essays by a raft of notable critics including Barry Bergdoll, Wilfried Wang, Jean-Louis Cohen, Juhani Pallasmaa and Robert Maxwell, as well as architects who have been influenced by Frampton, including Steven Holl, Rafael Moneo and Shelley McNamara and Yvonne Farrell of Grafton Architects. In the excerpt below, Mary McLeod recounts the development of Frampton’s ‘critical’ position.

Kenneth Frampton is arguably the most influential architectural historian since Sigfried Giedion. His book ‘Modern Architecture: A Critical History’ has been released in four editions and translated into thirteen languages since it was published in 1980, and his 1983 essay ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance’ may have been translated into even more. And despite serious criticism about the essay’s contradictions and limitations, including Frampton’s own subsequent reservations about it, it has probably had more impact on architects than any single essay published in the past fifty years, perhaps because of its ambiguities and contradictions: architects and firms such as John and Patricia Patkau and Brigitte Shim and Howard Sutcliffe in Canada; Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Grafton Architects and Sheila O’Donnell and John Tuomey in Ireland; Wang Jun-Yang and Rocco Yim in China; and Marina Tabassum in Bangladesh have all cited it as inspiration. The list could run much longer. While the writings of other architectural historians, such as Reyner Banham and Manfredo Tafuri, may have had a greater impact on scholars, Frampton’s writings—a mixture of history, criticism, and analysis—have inspired architects, especially those practicing outside of the United States (in places where the notion of “regionalism” or “locale” may have more resonance and meaning than in the States). Frampton’s importance to architects might be compared to that of Vincent Scully, who gave credibility and support in the 1970s and 1980s to Louis Kahn, Robert Venturi, and the so-called ‘Grays’ —and thus helped validate the rise of postmodern architecture in the United States. Or, if one looks to Europe, one might compare him to Paolo Portoghesi and Charles Jencks, who likewise supported the emergence of postmodernism during this period. However, Frampton’s own influence on architects has been much broader and over a much longer period of time than that of those historians: it is genuinely global in its reach and has lasted more than fifty years. In describing his own role in architecture, Frampton modestly prefers the word ‘writer’ to ‘historian’, ‘theorist’, or ‘critic’. But this choice of words might also reflect his refusal to draw sharp distinctions between these categories. He freely admits to being engaged in ‘operative criticism’, the practice that Tafuri had so severely condemned in ‘Theories and History of Architecture’ in 1968.

Born in 1930 in Woking, Surrey, England, Frampton initially considered a career in agriculture and then opted for architecture, studying first at the Guildford School of Art and then in London at the Architectural Association (AA), where his teachers included Arthur Korn, Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, and Alison and Peter Smithson. After graduating and working briefly at Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, he spent two years in the British army (which he describes now as a complete waste of time), followed by one highly productive year working in Israel for the modern architect Dov Karmi. Returning to Britain in 1959, he spent a brief period at Middlesex County Council, and then from 1961 to 1965 was employed at Douglas Stephen and Partners in London, where in 1962 he designed the housing complex Corringham (13–15 Craven Hill Gardens) in Bayswater, a project indebted both to Le Corbusier and to Soviet designers of the 1920s. During this period, Frampton was also influenced by James Stirling’s early architecture, especially his Leicester Engineering Building (which he considers a kind of synthesis of Alvar Aalto and Constructivism). In addition, while at Stephen’s office, Frampton wrote and co-edited his first book, British Buildings 1955–65, and served, from 1962 to 1965, as technical editor of Architectural Design (AD). Inspired by Ernesto Rogers’s journal Casabella continuità and Gae Aulenti’s graphic design, he sought to give AD greater visual clarity and a more European outlook, producing several notable issues on those he considered “local” architects working in a specific European cultural context, such as one devoted to Angelo Mangiarotti and Bruno Morassutti, and Gino Valle, the latter practicing almost exclusively in Udine. Later he would claim Valle as a “critical regionalist” and then as a representative of “tectonic culture,” but at this earlier stage the word ‘critical’ was absent from his writings. In 1966, Frampton left England for the United States to accept a teaching position at Princeton University, where he remained until moving to Columbia University in 1972. For American architecture students in the late 1960s and 1970s, he was probably best known for his 1968 article ‘The Humanist versus the Utilitarian Ideal’, an analysis of Hannes Meyer’s and Le Corbusier’s entries for the 1927 League of Nations competition. In that opposition, he sided not surprisingly with the humanist Le Corbusier, concluding the essay by declaring that Le Corbusier’s project offered the possibility of both unifying and differentiating people in a moment of mass society. (Here, he cited Hannah Arendt, who remains to this day a touchstone for his thought). It was this essay that led Robin Middleton, then the technical editor of AD and an acquisitions editor of Thames & Hudson, to ask him to write a new survey of modern architecture.

Above: Kenneth Frampton (project architect), Douglas Stephen and Partners, Corringham housing complex (13–15 Craven Hill Gardens), Bayswater, London, 1962–64.

During this period, Frampton was not especially political (he describes himself as “politically naive”) or engaged with political theory other than Arendt’s ‘The Human Condition’, which he read first in 1965 at the recommendation of Sam Stephens, a kind of polymath who taught architecture history in a “wildly sporadic fashion” at the AA. However, as mentioned above, in the early 1960s Frampton was already interested in Constructivism; its fascination for him, though, was more aesthetic than political, having been sparked by Camilla Gray’s pioneering book of 1962, ‘The Great Experiment: Russian Art 1863–1922’. It would not be until 1968 that his political and aesthetic interests would begin to conjoin – and it was in that same year that he began writing about Constructivist architecture, a subject largely missing from both Giedion’s and Banham’s surveys of modern architecture. By that time, Frampton was also a Fellow at the New York-based Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS), and in 1972, he would become one of the founding editors of its journal, Oppositions. Also in 1972, he began teaching studio and history at Columbia University, where he continues to teach today. Shortly thereafter, he designed his first and only realized building complex in the United States, Marcus Garvey Park Village in Brownsville, Brooklyn, sponsored by IAUS. It was during his early years in the United States that Frampton began first to use the word ‘critical’ to characterize his own writing and teaching.

Kenneth Frampton’s ‘Modern Architecture: A Critical History’

Today, we take the word ‘critical’ almost for granted as a term to describe both certain tendencies or ambitions in writing architectural history and certain kinds of architecture. Its usage has become almost ubiquitous, and it seems to serve as a trope indicating both analytical rigor and ‘leftist’ political sympathies. In the past seventeen years or so, the word ‘critical’ may have become better known in architecture circles for its countercurrent, the ‘post-critical’, promoted by Robert Somol, Sarah Whiting, and Michael Speaks. Around 2002, these three then-young rebels reacted against certain poststructuralist currents in architecture, such as Derridean deconstruction and Lacanian analysis – that is, the arcane discourse that had dominated the journal Assemblage and so much of architectural theory in East Coast schools in the United States since the mid-1980s. In their view, theory had become removed from the new parameters of practice—namely digital technology and parametric design; and just as important, it denied the sensual experience of architecture. Parenthetically, this use of the word ‘post-critical’ in architecture is quite distinct (even if it overlaps in its appreciation of the sensual) from the much earlier philosophical position taken by Michael Polanyi or William Poteat, first articulated by Polanyi in the 1950s. These two thinkers sought a more encompassing form of knowledge, one that would go beyond traditional logic to embrace a personal knowledge of sense experience; in this regard their position shared much with that of Maurice Merleau-Ponty and indeed many of the figures whom Frampton himself admires, such as Arendt (despite political differences).

Frampton was one of the first, if not the first, to use ‘critical’ in the title of an English-language book on architecture”

What is usually less recognized by architectural historians, theorists, and practitioners (whether pro- or post-critical) is how deeply indebted they are to Frampton for the term ‘critical’ in architecture – and how distinct his own position is from that which Somol, Whiting, and Speaks were rejecting (although undoubtedly, he would have some difficulties with their stance too). In 1980, Frampton was one of the first, if not the first, to use ‘critical’ in the title of an English-language book on architecture (even though it should be stressed that he was by no means the first in architecture to be concerned with this issue: he was preceded by the more explicitly Marxist studies of the Venice School). The word also appears in the titles of an issue of an AD profile that Frampton edited in 1982, ‘Modern Architecture and the Critical Present’, and of his influential 1983 essay ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism’. He employed it in his teaching as well – in his seminar Comparative Critical Analysis of Built Form, which he taught at Princeton University, beginning in the late 1960s, and then at Columbia University intermittently for almost fifty years. This pedagogical approach is encapsulated in his recent book ‘A Genealogy of Modern Architecture: Comparative Critical Analysis of Built Form’ (2015), which provides an eloquent synopsis of many of the concerns that have shaped Frampton’s teaching over the years.

But what specifically does Frampton mean by ‘critical’? Although he gives us a few hints as to its meaning, it is not something he has ever discussed at length. One might say the word is almost synecdochical for him, in that it stands for a larger set of social concerns and agendas, including his commitment to leftist politics, which he has only occasionally articulated at length.

The word ‘critical’ has a long history, one that derives from the Greek word kritikos, meaning ‘judgment’ or ‘discernment’. Its modern usage derives from Immanuel Kant’s three Critiques, especially the ‘Critique of Pure Reason’, in which he attempts to examine the limits of validity of a faculty, type, or body of knowledge through reflection; and then from Karl Marx’s critique of political economy in ‘Capital’, in which critique is seen as kind of ideological dismantling, revealing the contradictions within capital itself. In general, this has meant that the word is associated with a certain kind of critical self-reflexivity (an examination that goes beyond intention or popular reception) and, in the case of Marxist theorists, a belief that such critical examination can contribute to social and political transformation. But Frampton’s source, more specifically, like that for many others of his (and the following) generation, is the Frankfurt School, the group of scholars who worked at the Institute for Social Research in the 1930s, including Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse, as well as those thinkers closely affiliated with it, such as Walter Benjamin. These scholars attempted to extend Marxism’s ideological critique to the cultural sphere and to examine how mass culture had changed art’s production and reception – and thus possibilities for radical social transformation. Critical Theory was intended to produce a kind of knowledge – one grounded in the historical context of both the object of study and that of the researcher – that was both elucidating and emancipatory. Thus, in contrast to positivist knowledge (which envisions natural science as a model of all cognition), this knowledge was seen as a form of action or praxis, and thus a means for social betterment. This objective, too, is fundamental to Frampton’s own work. Frampton was among the first in the English-speaking architectural world to read and reflect upon the Frankfurt School and, specifically, Benjamin’s writings. His introduction to his first edition of ‘Modern Architecture: A Critical History’ begins with a quote from Benjamin’s ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ (1940):

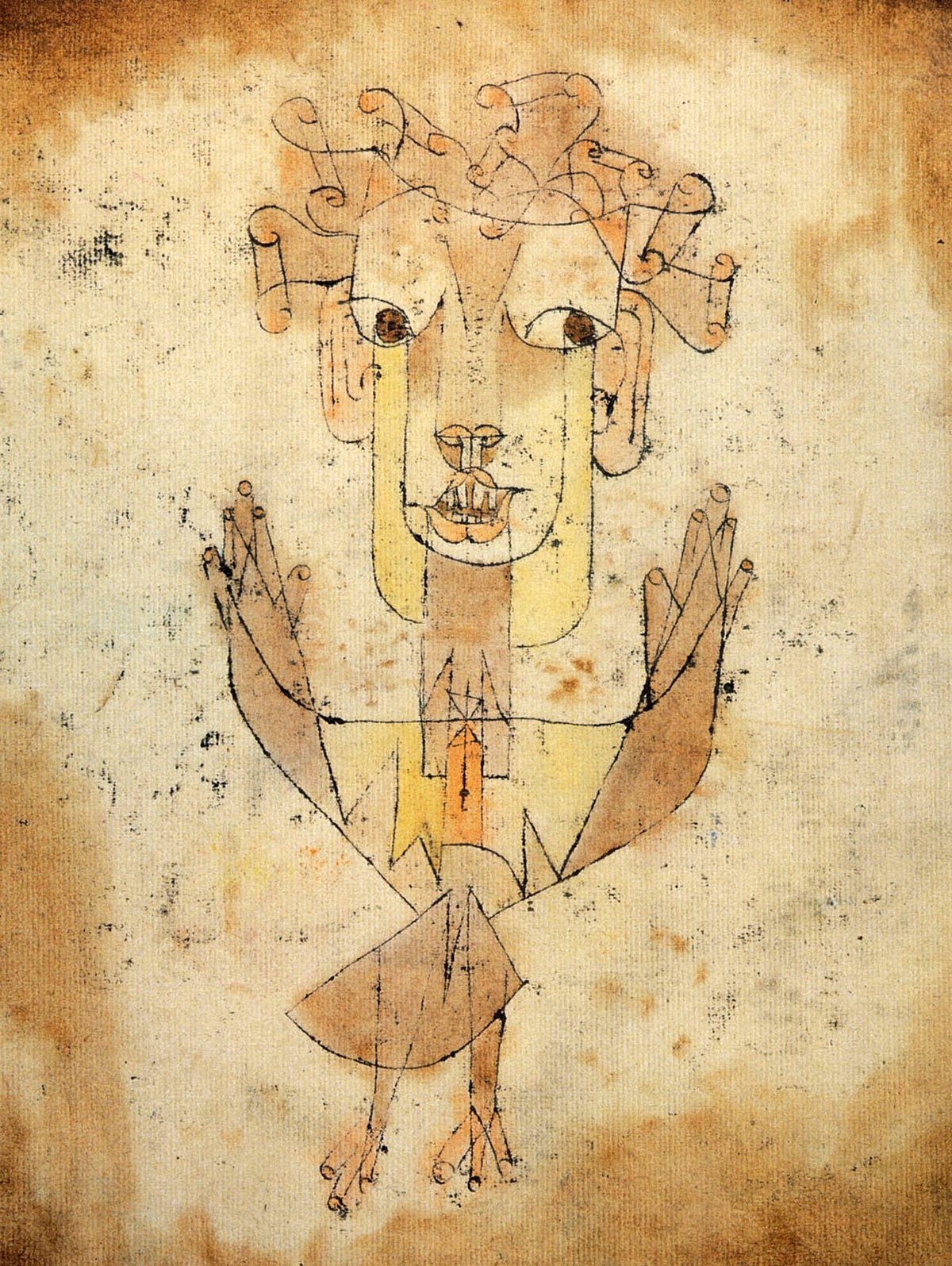

“A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is in fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned towards the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise: it has got caught in its wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress”.

Later in that introduction Frampton states that he was influenced by a Marxist interpretation of history, and refers to his “affinity with the critical theory of the Frankfurt School,” adding that it made him “acutely aware of the dark side of the Enlightenment.”

Kenneth Frampton, Marcus Garvey Park Village, Brownsville, Brooklyn, New York, 1973–76. Rendering by Craig Hodgetts showing a view of a cul-de-sac to the street. The low-rise, high density housing project was the only realised work resulting from a collaboration of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies and the Urban Development Corporation.’

His interest in Benjamin and the Frankfurt School, however, precedes by more than a decade the publication of ‘Modern Architecture’. In fact, he had already decided on the subtitle of the book in 1970, when he agreed to write the Thames & Hudson survey, and in 1972, he used the same passage from ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ that opens ‘Modern Architecture’ as an epigraph for his essay ‘Industrialization and the Crises in Architecture’. This essay was published in the first issue of Oppositions and, later, he would characterise it “as a somewhat naïve attempt to adopt a Benjaminian approach to historical phenomena.”

How did Frampton discover Benjamin and, more generally, leftist politics? Perhaps, not coincidentally, his seminal essay on Pierre Chareau’s Maison de Verre appeared in the same 1969 issue of Perspecta, Yale’s student-produced magazine, as Benjamin’s synopsis of his Arcades Project, ‘Paris: Capital of the Nineteenth Century’. In some regards, this meticulously designed issue – the embossed cover of which evokes the rubber floor tiles of the Maison de Verre – encapsulates both sides of Frampton’s thought: his deep concern for architecture’s formal and structural qualities and his social and political investigations, which sought to establish the links between politics, social conditions, and form. But more importantly, the 1960s were a moment of intense political engagement for many in the United States: first, the civil rights movement, followed by the increasingly intense protests against the Vietnam War, and then the women’s liberation movement. Frampton has said that, paradoxically, it was going to the States that “radicalised” him. He explains his conversion by quoting a comment that the English architect Michael Glickman once made to him: “You have to understand, in England the claws are hidden but in the States they are visible.” In other words, the brutality and pervasive power of capitalism and the military-industrial state were blatantly visible in the States. Like others at Princeton’s School of Architecture, he was involved in the university strike in May 1970 after the Kent State massacre.

Frampton’s interest in Benjamin was undoubtedly sparked by his long-standing admiration of Arendt (still very much apparent in his 2015 ‘Genealogy of Modern Architecture’). Arendt edited and wrote the introduction to ‘Illuminations’, the first collection in English of Benjamin’s writings. The book came out in 1968, and included Benjamin’s best-known essay, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, as well as his ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’. These two essays might be seen as embodying the two sides of Frampton’s interest in Benjamin during this period: on the one hand, his almost utopian faith in technology’s potential to improve human life and his deep commitment to mass housing, which parallels in some ways Benjamin’s position in the first essay; and, on the other hand, his increasing pessimism about society’s capacity to use technology judiciously and to sustain an authentic and meaningful culture in the face of ever-sweeping modernisation, even as one accepts its inevitability. One thinks here of Paul Klee’s angel being blown forward, even as he looks to the past, in Benjamin’s ‘Theses’.

Two pages from Kenneth Frampton’s copy of Herbert Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization (New York: Vintage, 1962)

An additional influence on Frampton in the late 1960s was Frankfurt School philosopher Herbert Marcuse. Alan Colquhoun, who taught with Frampton at Princeton in the 1960s, had given him his copy of ‘Eros and Civilization’, first published in 1955 and reissued in 1966. In this book, which was seminal to the emergence of the New Left and a political strain of American counterculture, Marcuse focused not on class struggle but rather on the repression of eros, which he saw as a product of contemporary industrial relations, namely the alienated labour of “advanced industrial society”. Marcuse called for a non-repressive civilisation founded on non-alienated libidinal work, a goal reminiscent of that of the nineteenth-century French utopian socialist Charles Fourier. These themes resonated with Frampton’s own growing concern for craft, an attention to detail – what I might call ‘care’ – and for the sensuous aspects of architecture; or, put another way, his refusal to “separate the reality of work from the pleasure of life”, as he so succinctly stated in his 1976 essay ‘The Volvo Case’. The role that Marcuse – and more generally the Frankfurt School – played in the evolution of Frampton’s own thinking is most evident in the postscript to his 1983 essay on Arendt, ‘The Status of Man and the Status of His Objects’. Here, he mentions two issues that he felt Arendt, who was not a Marxist, had either suppressed or suspended in her conclusion to ‘The Human Condition’: “First, the problematic cultural status of play and pleasure in a future labouring society after its hypothetical liberation from the compulsion of consumption (Marcuse) and, second, the remote and critical possibility for mediating the autonomous rationality of science and technique through the effective reconstitution of … an effective political realm (Habermas).” Frampton’s copy of ‘Eros and Civilization’ is so well-worn and marked up that its cover and Colquhoun’s inscription have long since disappeared.

Thus, it is these two authors – Benjamin and Marcuse – who introduced Frampton in the late 1960s to the Frankfurt School and what came to be known as Critical Theory. They would soon be followed by Jürgen Habermas, whose ‘Towards a Rational Society’ was translated into English in 1970, and Adorno, whose ‘Minima Moralia’ (1951) was translated into English in 1974. Alessandra Latour, an Italian graduate student and teacher in urban design at Columbia (and then a committed Marxist), gave Frampton a copy of Adorno’s book, and he opened his 1983 essay on Arendt with a quotation from it, one that again encapsulates the mixture of despair and messianic hope that has characterised so much of his own writing since the late 1960s. Until the 1980s, very little by Adorno or Horkheimer had been translated into English, and Frampton readily admits that he never read cover-to-cover the one book that seems to correspond most with his own disdain of commodification and mass culture, Adorno and Horkheimer’s ‘Dialectic of the Enlightenment’, which had been translated into English in 1972. Adorno’s ‘Aesthetic Philosophy’ was not translated until 1984.

Two more thinkers, however – individuals with whom Frampton had direct personal contact – are crucial to understanding his interest in Marxist cultural theory, and, especially, in its potential application to architecture. The first is Tomás Maldonado, the Argentine concrete painter, industrial designer, and theorist, who succeeded Max Bill as Rector at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm and who was also a visiting professor at Princeton in the late 1960s. Frampton had already met Maldonado at Ulm in 1963, when he visited Germany as technical editor of AD; at that time he also first encountered a second individual, the Swiss-French Marxist Claude Schnaidt, who also taught at Ulm and who would write the first monograph on Hannes Meyer, a book that Frampton has long admired. Frampton discussed both writers in his 1974 essay, ‘Apropos Ulm: Curriculum and Critical Theory’, in Oppositions 3, which was his first published use of the word ‘critical’ in a title. In Ulm, he explained, he found a model for raising “critical consciousness of the role of design in contemporary society”. (Maldonado had used ‘critical’ in the subtitle of the 1972 English translation of La Speranza Progettuale, which was titled ‘Design, Nature, and Revolution: Toward a Critical Ecology’.) It should be noted, though, that Frampton’s use of ‘critical’ here has little to do with the Frankfurt School but rather with a more general commitment to a Marxist position that unites theory and action. In fact, Maldonado specifically cites Antonio Gramsci for his theory of ‘praxiology’ or ‘theory of practice’ – a “model of action oriented toward overcoming the dichotomy between theory and practice.” One of the most telling quotes in ‘Modern Architecture: A Critical History’ is from Schnaidt’s essay ‘Architecture and Political Commitment” of 1967. It is worth repeating in full, as it so eloquently summarizes the critical position that underlies Frampton’s own text:

“In the days when the pioneers of modern architecture were [still] young, they thought like William Morris that architecture should be an “art of the people for the people.” Instead of pandering to the tastes of the privileged few, they wanted to satisfy the requirements of the community. They wanted to build dwellings, matched to human needs, to erect a Cité Radieuse. But they had reckoned without the commercial instincts of the bourgeoisie who lost no time in arrogating their theories to themselves and pressing them into service for the purposes of money-making. Utility quickly became synonymous with profitability. Antiacademic forms became the new décor of the ruling classes. The rational dwelling was transformed into the minimum dwelling, the Cité Radieuse into the urban conglomeration and austerity of line into poverty of form. The architects of the trade unions, co-operatives, and social municipalities were enlisted in the service of the whisky distillers, detergent manufacturers, the bankers, and the Vatican. Modern architecture, which wanted to play its part in the liberation of mankind by creating a new environment to live in, was transformed into a giant enterprise for the degradation of the human habitat”.

With this statement, Schnaidt, and thus Frampton, was insisting upon the need to recognize the extent that modern architecture, despite its progressive intentions, had been shaped by the dictates of profit and capitalism; but also implicit in this passage, and perhaps even more clearly in Frampton’s conclusion to the book, is the desire to propose something more than Existenzminimum – a commitment to a richer, more fulfilling world. And here, we have again the particular synthesis that underlies so much of Frampton’s thought and what might be seen as the goal of his critical perspective: an architectural modernity that is not reduced to rational instrumentality and minimum dwelling, but rather offers a liberatory vision that enriches habitation and community life while still embracing technological progress. In other words, it is an architectural vision very much compatible with Marcuse’s broader cultural argument in ‘Eros and Civilization’.

Frampton’s discontent with architecture’s commodification and environmental degradation was further fueled by the rise of postmodern architecture and its increasing emphasis on scenographic effects in design. This is very apparent by 1982–83, the year of his AD issue ‘Modern Architecture and the Critical Present’ and the publication of ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism’ in Hal Foster’s anthology ‘The Anti-Aesthetic’. The anthology also included Habermas’s sweeping indictment of postmodern thought, prompted by the Venice Architecture Biennale of 1980, and in part the motivation for Frampton’s own essay (he was originally on the organising committee of the Biennale but soon resigned once he recognized the direction that Portoghesi’s exhibition would take). The intense debate among architects and social thinkers of the period arising from discussions about postmodernism had intensified Frampton’s awareness not only of the failures and limits of the Modern Movement’s embrace of technology and social transformation but also of the increasing complicity of contemporary architecture with the forces of capitalism. In other words, he used his citations of members of the Frankfurt School and Marxists such as Schnaidt and Maldonado to criticize both modern and postmodern architecture, if increasingly with a critical lens directed at the latter. But it might also be said, as Fredric Jameson later so brilliantly explicated in ‘The Seeds of Time’ (1994), that Frampton’s “arrière-garde” critique was itself participating in the celebration of pluralism and difference so typical of both postmodernism and late capitalism (that is, a post-Fordist economy that can customise its products for local markets), even as it sought to retain some vestige of utopian hope in its proposal of an “architecture of resistance.” One might say that he hoped to fashion a progressive strategy out of the materials of tradition and nostalgia (as well as a more considered use of technology) that would stand, even if metonymically, against the commodification rampant in late capitalism. Frampton continued to share with Marcuse a belief in art as a reminder of an alternative world, even as he acknowledged its incapacity to effect large-scale change, at least without the presence of larger political, social, and cultural movements.

Left: Cover of an issue of Architectural Design (March 1964) devoted to the work of Mangiarotti and Morassuti and Gino Valle. Kenneth Frampton would later claim Valle’s work as an example of “critical regionalism.”

Right: Cover of Modern Architecture and the Critical Present, Architectural Design Profile (London: Academy Editions, 1982). This publication, edited by Frampton, includes his critical commentary on current architecture, in addition to reviews of Modern Architecture by eminent architectural historians and critics.

As important as the Frankfurt School was to Frampton, his understanding of what a critical position might entail can also be seen as linked to another tradition, perhaps not consciously on his part, one that has been very much part of his thought since the early 1970s. Habermas, in his 1968 book ‘Knowledge and Human Interests’, distinguished between critical political and social theory, notably that of the Frankfurt School, and “self-reflective” cultural theory. He equated the latter with hermeneutics, a theory concerned with the meaning of human texts and symbolic expressions, one that effaces the boundary between factual and symbolic understanding. While Habermas acknowledged the “conservative” side of hermeneutics – that it is inherently concerned with existing meanings and cultural tradition rather than with new possibilities, and thus social transformation – he argued that it offers a necessary critique of positivism in its insistence on individual life experience which must then be adapted to general categories. Although literary critical theory is now associated with numerous other tendencies, including Derridean deconstruction, post-colonial theory, identity politics, gender studies, and even environmental analyses, this other – earlier – meaning of cultural theory that Habermas articulated seems to reflect Frampton’s own concerns for meaning and cultural expression (even if they have evolved over the years to include some of the approaches just mentioned). This is perhaps never so apparent as in his oft-cited and influential essay of 1983, ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism’, which opens with a long quotation from Paul Ricoeur’s 1961 essay ‘Universal Civilization and National Cultures’. Ricoeur, who is known for uniting phenomenology and hermeneutics and for extending hermeneutic investigation beyond the literary sphere, presciently posed the recurring quandary of developing nations (but one that affects all cultures): “There is the paradox: how to become modern and to return to sources: how to revive an old, dormant civilisation” – which he referred to earlier as “a cultural past” – “and take part in universal civilisation.” Frampton was introduced to Ricoeur’s work by the phenomenologist Dalibor Vesely, who had opted not to review Frampton’s ‘Modern Architecture’ in the 1982 publication of AD.

Embracing Ricoeur’s paradox – that is, between modernity and tradition or between universal civilization and regional cultures – Frampton proposed in his influential 1983 essay a strategy of arrière-garde action, a kind of holding operation, salvaging the cultural meaning of architecture against the onslaught of an ever-pervasive instrumental rationality. The variety of sources in this essay is itself telling: not only his beloved Arendt, but also Marcuse, Benjamin, and Heidegger – in brief, both the Frankfurt School and phenomenology. In the essay, Frampton tries to find a means of practice that would unite his Marxist sympathies and deep commitment to an egalitarian society with his phenomenological or experiential concerns emphasizing place, light, and tactility – in short, the sensual dimensions of architecture (in fact, the very qualities that the post-critical crowd found missing in so much poststructuralist critical theory). While Frampton’s effort to unite these two seemingly contradictory perspectives may be unique among architectural critics and historians – and distinct from Tafuri’s, let alone those of his IAUS colleagues – his struggle for such a synthesis was not so rare among philosophers, whether Marxists such as Marcuse and Henri Lefebvre, or existentialists and phenomenologists, such as Jean-Paul Sartre and the younger Merleau-Ponty, who attempted to reconcile their philosophical ideas with their political commitment to a classless society (even if they would later part ways about the necessity of proletarian revolution). Tafuri himself admits in his largely positive review of Frampton’s ‘Modern Architecture: A Critical History’ that such a reconciliation between these two seemingly disparate positions is possible, although Frampton himself has never tried systematically to do so in his writing. Only later would he read seriously Merleau-Ponty’s ‘Phenomenology of Perception’, a source that he cites in ‘A Genealogy of Modern Architecture’, where it would seem that the phenomenological strain in his thinking dominates.

Alvar Aalto, Saynatsalo Town Hall, Finland, 1949–51.

In ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism’, one senses, perhaps more than in any of his other writings to date, the importance of the word ‘critical’ for Frampton. He believed it was essential to distinguish his vision of regionalism from conservative appeals to nostalgia and tradition, and even from its lingering associations with Blut und Boden – a position he states forcefully in his third point. Nonetheless, one wonders at times if his commitment to political critique is undermined or mitigated by his reveries about architecture’s experiential qualities. Can the qualities that he so deeply values in architecture – such as tactility and the articulation of structure – really serve as modes of resistance, as a kind of arrière-garde holding operation? Is it possible to reconcile his belief in technology as a democratic and liberating tool that can improve living conditions for all classes, especially the most impoverished, with his rejection of mass culture and technology’s pervasive presence in American society, which he associates with mindless gratification and environmental degradation (television, highways, and air conditioning, etc.)? And given the proliferation of images and the homogenising effects of ever-increasing globalisation, is it possible to accept his elevation of structure over surface effects, or his emphasis on place and urban identity, especially in contexts that seem to defy any kind of regional or even topographical specificity? Like Lefebvre, who is not a central figure for Frampton but who also drew from both Marxism and phenomenology, Frampton seems to be searching for a logic (and, in his case, an aesthetic vision) that would embrace the paradoxes of two seemingly disparate worldviews in his search for reservoirs of resistance against the onslaught of ‘commodity culture’ and the ‘imperatives of production’. And in a manner somewhat reminiscent of Benjamin, he relies on a series of quotations and fragments, rather than one unified argument, to make his points. But whether one accepts his synthesis or not, or even fully embraces his aesthetic vision, what undoubtedly makes his position so appealing to so many architects is his belief that critique should not be purely negative – that is, it should not only serve to elucidate the shortcomings and contradictions of the status quo but also take the risk of proposing alternatives that might offer, however modestly, the promise of a richer, more fulfilling existence.

If over the years, Frampton has increasingly recognized the limits of architecture’s own transformative powers given the hegemony of global capital, he sees proposing positive examples of architecture as a “strategy of sidestepping – sidestepping a tendency toward closure that seems to constrain the living present in such a way that you sometimes feel you can’t do anything.” Although these models reflect an increasing concern for experiential qualities and what he calls the “poetics” of construction and structure, one thing has remained constant, as he recently stated: his “commitment to the socialist aspect of the modern project.” Here, his position seems closer to that of both Habermas and Gramsci, who emphasise culture’s potential as a constructive force countering prevailing ideologies, than to that of Tafuri and Adorno, who seem to accept a darker, more totalising view of capitalism’s power. In fact, one might argue that where Frampton departs from Tafuri is not so much as an operative critic – for Frampton’s models or preferences are not part of a seamless teleological narrative in the sense of Giedion or Bruno Zevi, two of Tafuri’s ‘operative’ historians – but rather in his willingness to propose strategies for architecture that might offer something more than the zero-sum game of market forces. To avoid closure, he seeks to present, as he has explained, a “wide variety of work”.

Jørn Utzon, Bagsvaerd Church, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1968–76.

But the gap between Tafuri and Frampton might not be quite as great as it first appears. At the conclusion of ‘Architecture and Utopia’, and after a relentless account of modern architecture’s “useless” utopianism and its serial failures to generate radical social change, Tafuri offers a glimmer of hope to architects: they might work in public offices as “technicians”, that is, organisers of building activities and planners of process, a role involving the dissolution of traditional disciplinary boundaries. Frampton’s hope, though, resides within architecture itself. He is still willing to see the generative – and positive – qualities of form and experience in order to create a space for architectural practice that resists the most blatant forces of commodification. Frampton is acutely aware of the difficulties of his own belief in the transformative values of both architecture and criticism, and in a 2001 interview with Gevork Hartoonian, he specifically addresses Tafuri’s rejection of “operative history”:

“I was recently re-reading the didactic introduction, wherein he [Tafuri] writes: “Doing away with outdated myths, one certainly does not see on the architectural horizon any ray of an alternative, of a technology ‘of the working class’.” I am aware that the Marxist ‘hard line’, then as now, thinks of my writing as operative criticism, as permitting the survival of anachronistic hopes of design as a liberative agent, which Tafuri dismissed as regressive. However, he also concedes that under present circumstances one is “left to navigate in empty space, in which anything can happen but nothing is decisive” – which sums up, I suppose, basically what I think about my position”.

In the last essay of Frampton’s book ‘Labour, Work and Architecture’, ‘Minimal Moralia: Reflections on Recent Swiss German Production’ (1997), a rather sharp assessment of some recent trends in Swiss architecture, he states in a beautiful passage what navigating – and writing – in this “empty space” means to him:

“One can only hope that others will be able to sustain their early capacity or, alternatively, to reveal an untapped potential for the pursuit of the art of architecture in all its anachronistic fullness. One perhaps needs to add that one does not indulge in critique for the sake of a gratuitous negativity, but rather to spur the critical sensibility, to sharpen the debate, to overcome, as far as this is feasible, the debilitating dictates of fashion, and above all to guard against the ever-present threat, in a mediatic age, of sliding into an intellectual somnambulance where everything seems to appear to be for the aestheticised best in the best of all commodified worlds”.