Shibam: a city shaped by desire and anxiety

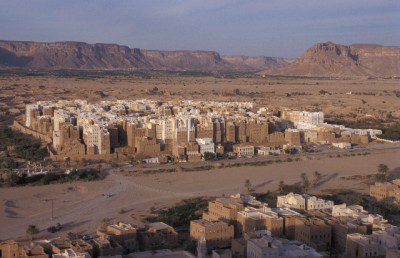

You are standing on the top of a hill looking down on the city and the Yemeni boy tells you that this city moved. He also tells you that the city is 3000 years old and it was once over there, in the distance, and now it is here, perched on top of a rectangular platform before us. You are drawn into his story, but you want to know why this ancient walled city, made of mud, is so extraordinarily tall. What are the forces at play that shaped the city of Shibam?

Is it because when the city moved to this new location, the platform could only accommodate its 7000 inhabitants if the density was increased? So they communally built a vertical city of 500 tower houses. Strategically sited on the caravan route that lead from the ancient source of frankincense on the island of Suqutra, the platform sat squarely in the middle of a vast valley called Wadi Hadramawt. The city’s location had brought it great wealth as a trading centre and there must have been great demand to live here. Perhaps desire shaped the city.

Is it because in times of trouble a tall tower was a comparatively safe place to be, so the houses grew vertically through five to nine storeys tall? Storerooms with tiny windows in the base, stalls for animals above, then meeting rooms for strangers, then family rooms, and finally the living room at the top adjoining the roof terrace. There are links between neighbouring houses, sometimes in the form of bridges that offer safe passage. Perhaps anxiety shaped the city.

Is it because mud was plentiful that walls which needed to be one metre thick at the base, tapering inwards as they went upwards, were achievable without great cost? Stone, used sparingly for the foundations that produce a visible base, rose discretely up through the central pillar of the stair core to offer dependable stability. The mud whose straw content glistens in the sunlight makes a soft and quiet city as it absorbs all the sound and gives the city its distinctive character. There is certainly plenty of mud in the river valley but the best mud came from the groves of date palms as it offered excellent binding properties. Perhaps abundance shaped the city.

Is it because rain was the main enemy of the city of mud that to have a small exposure to the sky reduced the destructive capacity of the rain? Seasonal torrential rain brought floods that turned the river valley into fertile plains but also destroyed the city once in 1298 and again in 1532. It was always rebuilt in exactly the same form. As protection the bases and the tops of the mud towers are covered sparingly in white lime plaster. The oldest buildings that have endured, protected with the greatest amount of white plaster, are the important buildings – gatehouse, mosques and sultans’ houses. Perhaps rainfall shaped the city.

Is it because the heat was so overpowering in Wadi Hadramawt, whose name meant ‘burning heat’, that these towers were built as tall as possible to cool themselves? Being near the equator a tall house takes less sun on its facade. The ancient principle of the thermal chimney cools the houses: the greater the height, the greater the airflow. Cool air is drawn in from the deep shaded streets and sucks the hot air out of the rooms as it rises up through the stair core. This blissfully simple technique is supplemented by an array of windows. Tall narrow window with perforate screens prevent small children from falling as they draw cool air at low level, and small narrow windows push the hot air out near the ceiling. Perhaps heat shaped the city.

Perhaps all of these factors and more have cumulatively shaped the city over a vast amount of time. Having spent many years travelling through many thousands of cities, Shibam is for me one of the most generous with the lessons. My kind of town draws me into a story, it makes me ask questions, and it requires me to look for answers with all of my senses.

Mike Tonkin is a partner in Tonkin Liu, whose recent projects include the Singing Ringing Tree in Lancashire and Promenade of Light in London

First published in AT209, June 2010