Watch our AT Schüco webinar exploring the value of net zero buildings and how their worth can be communicated to clients and investors.

Architects have been talking for so long about the need for more sustainable buildings that it is extraordinary, and encouraging, to finally see real progress being made. The prospect, like everything to do with the climate emergency is daunting – so much to do and so much to learn in so little time – but the commitment that is now coming from clients is cheering.

This webinar, on calculating the value of net-zero buildings, looked at the drivers for clients to commit to net zero and the arguments that can be made to convince them. The latter made little direct reference to the desire to combat global warming, instead, deliberately, they concentrated on cost, staff retention and future value.

Elaine Rossall, head of UK offices research at real estate services company JLL, quoted a US survey showing that almost 40 per cent of millennials choose a job because of the company’s sustainability policy, and that they would be willing to take a pay cut to facilitate this – a real commitment in difficult times.

Speakers from left to right: Gary Clark, Elaine Rossall, and Simon Wyatt

Not surprisingly, Rossall said that talent is one of the three main drivers for adopting sustainable behaviour. Staff are both the most expensive and most important aspect of most office-based organisations. Good staff are more productive, and loyal staff minimise the cost of recruitment.

Another driver is pressure from investors to embed sustainability at the core of businesses. In addition, companies themselves are committing publicly to sustainability targets. The number is, says Rossall, ‘growing exponentially’, with more than half pledging to be net zero carbon. If these companies want to reach a target before 2030, that means that the next lease they sign will need to be for a much greener building.

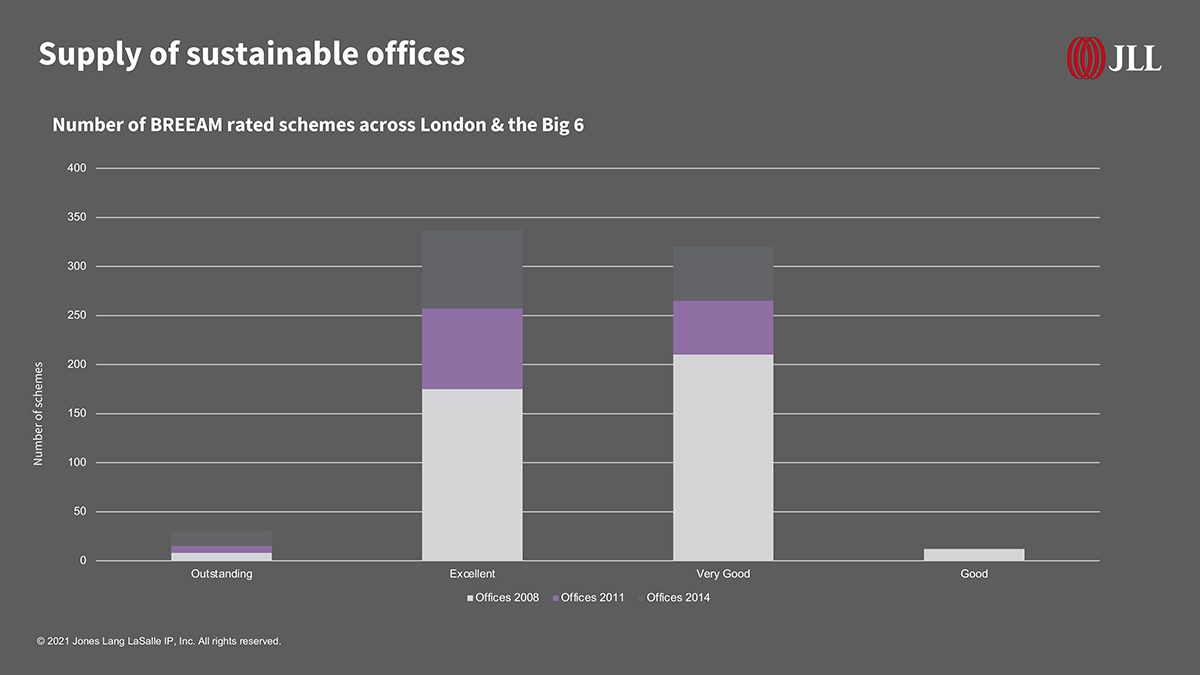

Table showing the supply of sustainable offices across London and the ‘Big Six’ regional markets

The supply of sustainable buildings is, said Rossall, less impressive. Just over 10 per cent of the office building stock in London and the six main regional markets (Birmingham, Bristol, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds and Manchester) has a Good to Outstanding BREEAM rating. And while several buildings claim to be net zero carbon in operation, there are as yet none that have net zero embodied carbon. Developers, said Rossall, are beginning to wake up to ‘a real gap between demand and supply’.

Although upfront costs can be a barrier, sustainable buildings do, she said, achieve higher rents, and are let more quickly. She concluded, ‘There is a wave of occupiers ready and waiting for net zero and more sustainable buildings. There is currently a premium opportunity, but this will move fast to brown discounts on less sustainable buildings.’

Clad with full-height living walls, Make Architects’ New Bailey commercial building in Salford is targeting net zero carbon in operation (cgi: Make Architects)

Simon Wyatt, a partner at engineer Cundall, talked about the different definitions of carbon neutral and net zero carbon buildings. Whereas carbon neutral buildings simply offset their emissions, net zero carbon is more demanding. Before you start offsetting, the building must have emissions that are limited to meeting the trajectory of a 1.5°C rise by 2050.

‘Most of industry,’ Wyatt said, ‘is setting aspirations around net zero carbon.’ And a few, he said, are looking at absolute zero, which involves no offsetting and is ‘extremely challenging and interesting’. Even without this new ambition, the words challenging and interesting still apply. A typical office currently uses around 300kWh/m²/year of energy, and the best 25 per cent are nearer to 200. But in order to get down to the Paris targets, this figure should be closer to 70kWh/m²/year, which Wyatt described as ‘a systematic step change’.

CRREM trajectory curve demonstrating the cost of inaction

He also talked about the idea of stranding, where assets become nearly valueless because they no longer meet regulations. This, Wyatt argued, puts a different complexion on an initial cost premium that is typically 5 to 15 per cent. ‘We need to compare the whole-life cost,’ he said. ‘If we don’t do it now, we will need to retrofit to comply with stranding.’

The final speaker, Gary Clark, is principal and head of science, technology and sustainability at HOK’s London studio, as well as honorary professor of sustainable architecture at Queen’s University, Belfast. He argued that we need to debunk the idea that we can’t afford the capital cost of green buildings.

Sustainable life cycle value outcome

The capital cost increase is likely to be 10 per cent as a worst case scenario, he said. If technology is kept simple, it is likely to be less than this. Set against this are energy savings, significant increases in productivity and health, and reduced maintenance costs – providing that the sustainability comes from a simple, fabric-first approach rather than a lot of complex systems. In addition, there is likely to be a rental premium of around 10 per cent, and a social value that is virtually impossible to measure.

As energy costs continue to rise, the financial savings in terms of operation are going to increase. All this is before any appreciation of a contribution to mitigating the climate emergency. The question, said Clark, should not be ‘Can we afford to do this?’ but ‘Can we afford not to do it?’