Jay Gort talks to architect and academic Matthew Barac about The Rock, a house designed by Gort Scott Architects for an extraordinary site in the Canadian mountain resort of Whistler.

Photos

Rory Gardiner

The pair discuss eclectic architectural references, the relationship between sculptural expression and family life and responding to the unique qualities of an extraordinary site.

Jay Gort The client had a real connection to this particular site. He’d found the site a few years previously and had this dream to build a house on this particular point. He hadn’t built a house like this before and he wanted to do it in a very personal way and to take time in selecting the right architecture partner, so he decided on a competition.

Mabel Law, who is an interior designer based in London and had worked with the client on an apartment in Hong Kong, helped put together a long list of 20 architects. At that time, the practice was around six years old. We’d done a small house in the Isle of Man and a few other little extensions here and there. I think the client had requested that it wasn’t going to be architects that had done this lots of times before. He made his money through buying and investing in companies and making successes from those, and he saw there was a chance to build a relationship with a younger practice and do something quite special. He’s an extremely trusting client.

Then we were selected to be one of three or four practices to take part in the design competition. We got a modest honorarium, which we used to pay for flights. We wanted there to be a real reciprocity between the landscape and the building and we just felt it was absolutely essential to visit the site. We spent five days camping there. We’d be up there from first thing in the morning to last thing at night; sketching, drawing, listening to the sounds, looking at the way the light fell through the trees, identifying particular viewpoints –just really trying to understand the site and to absorb and soak in as much as we possibly could. Obviously, here, we have some really quite unique qualities of the landscape. But really our approach is the same for all our projects. The relationship to context is key. That doesn’t necessarily mean we want the building to blend in or sit comfortably or be a simulation of what’s adjacent to it. It’s about the process of looking really closely at a site and trying to reveal the unique qualities of any particular place.

We wrote a short diary of our time on the site and the experience of walking to the top of the rock and the different sensations you experience. The whole premise of the project was to try and capture a sense of what it was like to walk up and get to the top of that rocky crest on the edge of the lake. At the foot of the rock there is this public park where you get people paddleboarding and sunbathing in the summer. There’s a bike track. It’s got a lovely hubbub. When you’re on top of this rock, you’re looking down at that and you can feel somehow connected to it, but because you have this huge cloak of trees and you’ve got Whistler Mountain behind you as well, you feel very protected and shielded at the same time. I was trying to capture that spirit: the contradiction in the sensation of being on top of this rock whilst being enclosed as well, and the client said that was exactly the feeling he had when he was there. I think that was what really appealed to him: the fact that he felt there was somebody in tune with the way he’d reacted to the site.

Matthew Barac It is an escapist fantasy, but on the other hand it’s rooted in realness. It’s very tectonic, it’s got a weight to it, but it’s a weight that is all about the embodiment of the rock and the realness of the materials and the texture of the concrete and its weight, but at the same time a very heady sense of articulation. It is very thoughtful, but also spiritual. The word that springs to mind is cosmological. It’s all about the ground and the sky but at the same time it has this highly articulated geometric aspect and a real interest in horizons. So that idea of it being rooted in realness, I think, is something we need a lot more of right now. We’re all sick to death of virtuality and unreality and not being able to go outside and be in real places with real people.

Jay Gort It’s very much about the life that goes on there. It’s a house for a husband and wife and three children to live in as their primary residence, so it’s not just a holiday house. Rory Gardiner’s photographs are very composed. His approach is to really try and capture the light and the way it works on the materials. They’re very beautiful. But when you’re there – and we’ve become friends with the family and have spent a lot of time there – it’s all about the chaos of family life.

So the kitchen area, dining area, a snug, living room are all on different levels relating to the existing topography. They’re open plan and spatially fluid. On the one hand it feels very sculptural. But when you see it in play, they’re a really easygoing family and they really occupy the space. The father might be at the table working with his laptop, someone’s cooking, someone’s working in the study, the son will be playing on the carpet with Lego all over the place. It feels like a lot of the interactions we imagined from the start are playing themselves out.

Another thing you don’t get from the photographs is that the acoustics are really carefully considered. Behind the soffit where the oak timber ceiling is, there are tiny perforations where there’s quite thick acoustic insulation. And there are rugs on the floor. So as you step into that space, it’s really quiet, which stops it from feeling like a public building or a museum. The whole experience of being there feels very natural.

Saying that, the whole idea of movement through the building was very carefully choreographed – the whole idea of how you could make that journey to the top and capture some of the essence of climbing up the rock. But we were very conscious of it not becoming just about the journey but about dwelling and stopping. The series of interconnected spaces is like a collage. Where you’re in one of those spaces, you feel grounded by the relationship to the landscape. So the dining table is orientated to get the west light from over Rainbow Mountains to the west as it comes through in a particular time. The breakfast bar in the morning gets the east light coming through the forest at particular points. The music room has very particular views.

Even though it has a lot of sculptural qualities, it emerged, first and foremost, through thinking about human situations and how you really live in that space. So alongside the more formal investigations about the topography and the section and the plan and the models – and the research into the site and the views – we spent a lot of time really trying to get under the skin of how the family were going to live, and how we could allow them to live in different ways in the future as well.

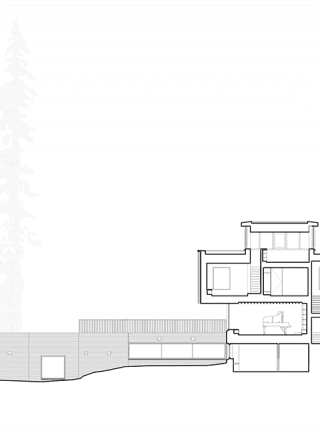

Matthew Barac The implication that this house is in any way an ordinary domestic setting is not very tenable because it’s clearly extraordinary. And it’s very large. But it’s definitely not formal. It’s not like a stately home in any way. I remember many years ago, one of the partners of ORMS talking about a large project they had been commissioned to do for a family and saying one of the difficulties for many British architects is that we don’t do these grandiose homes in the UK. It’s either bijou or a stately home. And this is a home which is absolutely expansive. So I think that there’s definitely a reading of how the family wants to live. But that dialogue between formality and informality and the way that the home might create those areas of separation for different members of the family is indicated not just in plan but in the section. I think the section is really important here.

Then there’s the issue of journey and of pilgrimage. As you said, the sense of pilgrimage when you get inside the house is quite pronounced but it’s not just a movement into the different parts of the house. It’s very much a vertical journey. You come in through an extraordinary cave-like entrance space. And then you move either up the staircase towards the light, or into a space beneath the living area, which is where the two kids’ bedrooms are. And that’s really interesting. The kids do have their own domain. So immediately, the sense of the house accommodating the different desires and requirements of the different members of the family is very much present. And then two floors up is where the parents have their suite – their world – and it’s a world of beautifully crafted timber. And the space in between is this interior landscape, which is something of a stage set. So it very much represents a vision of architecture. I do think it’s a manifesto house. It has something of the Raumplan of Adolf Loos’ Villa Müller but here it’s completely exploded because it’s an open-plan Raumplan.

That theatricality of overlooked spaces and through views is really interesting. There are these subtle moments of articulation, which are brilliant. When you’re in the living room, you can see the lake behind you. But if you look the other way, if you look east, you’re looking across the pool directly towards the Whistler Mountain in the distance, and it’s literally on the axis with the pool. So the pool suddenly ends up being almost like a piece of geometric signage. It’s pointing you at the mountain. You can swim in this pool under the mountain, and then go to the living room to dry off and look down on the real lake below.

When you look quite carefully at the plan and the photos together, you start to recognise the cues with regard to this journey and the relationships that start to appear to you. It’s a very modernist exercise, but it’s postmodern as well, in the play between pictorial moments of visual experience. There’s a slight fetishism in it. There’s an obsessiveness to some of the detail, which is like those very studied aestheticised experiences of some of David Adjaye’s houses, for example, where a very shiny surface is then in play with a heavily artificial painted surface. And there are those moments which are quite compositional that also remind one a little bit of some of the work of Eric Parry – that extraordinary thing that he did in the Château de Paulin in France – where the care with which certain highly articulated moments are made is then in dialogue with moments where the material is really celebrated for its fundamental roughness and unfinishedness.

Jay Gort That exploration of materiality and construction and craft was a really important part of the project. The whole team – me and Fiona Scott and Joe Mac Mahon and Andrew Tam and everyone who worked on the project – approached it with such dedication and care. Everything you see was drawn in such detail. And we were working with a brilliant contractor, Dürfeld Constructors, who really rose to the challenge. We had a really great team of consultants. I think that because the clients and the design team had taken such care over the project, from those early sketches, to conversations and drawings and physical models, the contractors really took that on board as well. No one wanted to let the team down. Everybody was seeking perfection in what they were trying to do.

All the various consultants were from the local area, so that brought a lot of local knowledge. Initially we assumed we’d have to have an executive architect on board. In the end, we did it ourselves but we worked with Kat Sullivan, who used to work for the municipality in planning and building control. She was brilliant in helping us to navigate the regulations. The concrete contractors were incredible. The entire concrete substructure was produced in one pour as one completely interlocked rigid, three-dimensional puzzle. The structural engineers, Equilibrium, are based in Vancouver, and they were brilliant in terms of designing for extreme weather. It’s about using the snow as your friend. In the winter, you get this complete change. The lake is iced over so you can walk across it. There’s deep snow. The design code for the area suggested you should be building what the client referred to as a Snow White House. But those steep roofs don’t hold the snow on them. We had to think very carefully how you drain from those terraces and decks, but there’s something fantastic about holding the snow on the roof in terms of thermally insulating the building. And there’s no reason for a house in this part of the world to reference an Alpine Lodge.

View from the terrace looking towards the study with the recessed music room below. The living room is in the background at the north west end of the pool.

Matthew Barac This house does have some magpie references, and it invites interpretation, which is one of the nice things about it. There are all kinds of references, whether it’s Frank Lloyd Wright or Carlo Scarpa or Scharoun and even Aalto. And Far Eastern references. I’m thinking of Chinese cities or fortified towns, where you get the bottom of the building coming out of the ground; walled houses made of stone or cement, the same colour as the earth. And then with these blackened hats, which are almost like pagoda hats sitting on top. That sense of being able to adapt and adopt different forms of influence and inspiration into an architecture which is very much unified, and feels like it belongs, is a credit to the architectural imagination.

Jay Gort The client was quite interested in some of the monasteries in Bhutan. It wasn’t a case of “can you design it like this?” It was more a case of different conversations that became embedded in the imagination as we went along. That journey of working with the client was a really inspiring process. And I have to say, he’s really, truly delighted. He talks about how it’s transformed the life of the family and the way they live and the connection that they have to this very special place.

Additional Images

Download Drawings

Credits

Architect

Gort Scott

Structural engineer

Equilibrium

Building envelope engineer

JRS

Landscape architect

HAPA Collaborative

Main contractor

Dürfeld Constructors

M&E consultant

MCW Engineers

Lighting consultant

EOS Lightmedia

Audio-visual consultant

Millson

Code consultant

Kat Sullivan

Swimming pool consultant

Alka Pool

Specialist millwork subcontractor

Leon Lebeniste & Krause Woodworking

Glazing subcontractor

Glasbox

Concrete contractor

Bmak

Landscape subcontractor

Another View