My Kind of Town: Edinburgh is a place to lose yourself, exploring, pausing and speculating

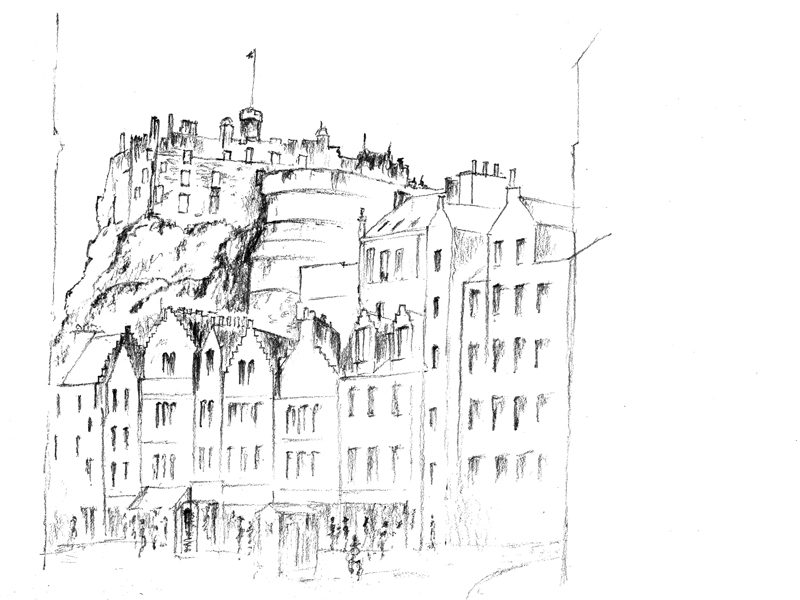

Arriving into Edinburgh by train is to be delivered directly into the city’s bowels; as you emerge from the station into the low northern sunlight on Waverley Bridge the assault of this place is immediate, evocative and sensory. Edinburgh castle looms in the distance; standing guard over your decision to turn left over the bridge to an unfolding world of myth, underworld and narrative of the Old Town, or right towards the more open, formal and genteel invitation of the New Town.

As a young architecture student arriving 25 years ago, assailed by the thin sound of bagpipes, the smell of brewing hops drifting from an indeterminate place and the chatter of almost indecipherable accents, I chose left, the Old Town. Subconsciously I was drawn by its romantic yet foreboding character, a decision which has influenced the way I have read landscapes and places ever since, searching for sensory stimulus to assist in uncovering stories and framing memories.

Subconsciously I was drawn by its romantic yet foreboding character, a decision which has influenced the way I have read landscapes and places ever since”

Edinburgh is a fascinating city of layers that knit together the Old and New, both metaphorically and literally, across the two sides of the valley. Beneath the streets of the Old Town lie abandoned vaults and passages that over the centuries have been rewritten above ground. These subterranean spaces were once home to an artistic and hedonistic underworld, neglected out of public shame and places that you avoided on dark nights.

Today they are once again a focal point for the arts and seekers of pleasure. As a young student with a sketchbook to fill, I was drawn to explore these forgotten paths and underground worlds. I loved to explore the ‘wynds’ and passageways, accessed from the sloping Royal Mile, which seemed to sink further and further into the city’s depths. On entering a typical wynd, you are struck by its narrowness and how it frames views of Edinburgh’s New Town skyline. Natural light is quickly suppressed as you are enveloped in a labyrinth that, without warning, ejects you into another street (commonly nowhere near the one you expected to end up in).

The city is defined by its steep topography, spaces between and below. Hills, stone staircases and endless vertical circulation is necessitated by its geological formation, as it sits on a ‘crag and tail’ volcanic plug. Streets are layered in criss-cross fashion, one on top of another, in a way that is almost impossible to imagine in section. It is a place of inter-connectivity where grand external staircases link the different strata of the city while internal stone staircases, hidden inside vast tenement blocks, provide access to as many as 20 flats. These are the seventeenth-century vertical streets, where day-to-day activities gain an almost theatrical quality, played out within full hearing and view of neighbours.

For me, Edinburgh’s joy is not just the great stone monuments and cultural wonders, but also the ability to completely lose oneself within the city, exploring, pausing and speculating. The city is really the size of a large town and is best explored on foot. As such, it is difficult to become too lost and you quickly begin to feel at ease with the place which will lead you, if you let it.

I recently visited again after too long an absence and was immediately aware of the scale of development and rewriting that is taking place. Vast swathes are being rebuilt: sadly a few shiny examples exhibit a lack of understanding and appear placeless. While these lost opportunities saddened me, there were some interventions that did demonstrate a deep understanding of this wonderful city, adding their own layer of confident modernity, without seeming at odds. This gave me hope that while Scotland deliberates over its political identity, my former home – and my kind of town – is a place where the urban fabric has now achieved independence appropriate to the times and will avoid stagnation through thoughtful place-making and the addition of well-considered new built form.