Allies and Morrison’s Passivhaus student village for St John’s College, Cambridge, offers a quietly persuasive model for academic institutions grappling with the demands of net zero, student wellbeing, and urban integration.

Cambridge’s largest Passivhaus student development, Hinsley Lane, accommodates 245 undergraduates and postgraduates across 39 shared townhouses. Commissioned by St John’s College, Cambridge, and designed by Allies and Morrison, the scheme offers a thoughtful alternative to the more standardised ‘pile-em high’ model that dominates the UK student housing sector. A series of red-brick terraces set within a sequence of shared gardens, it recalls the scale and sociability of a traditional college setting, and yet it sits quietly within a leafy, low-density suburb on the city’s inner western edge.

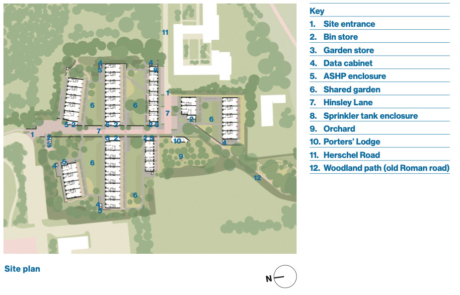

Just two kilometres west of Cambridge city centre, Hinsley Lane nevertheless feels distinctly peripheral. The site lies within a relatively undeveloped part of Cambridge, an area shaped by college ownership and a semi-rural character that have resisted the urbanisation seen in other parts of the city. Known historically as Grange Farm, the site once formed part of St John’s agricultural estate, supplying produce to the University. In more recent years it has become a patchwork of orchard remnants, scrubland and mature trees, including a hedgerow aligned with the route of an old Roman road – features that now form a naturalistic backdrop to the new development.

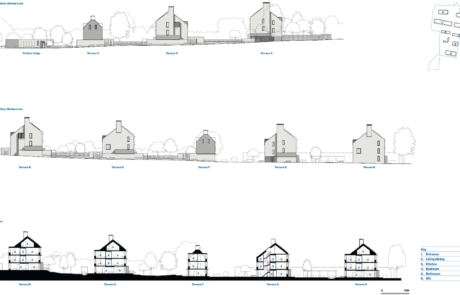

The lane is abutted by carefully detailed three-storey gable ends punctuated by outbuildings and chimneys. Shared gardens can be glimpsed through brick archways and metal railings on low brick walls.

The site falls partly within the West Cambridge Conservation Area, a protected enclave of red-brick, Arts & Crafts houses set within leafy informal plots. Described in the Conservation Area Appraisal as “an effusion of green… fusing the area together”, this part of Cambridge is characterised as much by its landscape as its architecture. Hinsley Lane had been earmarked for some form of college-based housing by the 2006 Local Plan, but it was not until 2019 that St John’s College began to bring forward proposals for the site, settling on a model that would focus on the needs of postgraduate students, either for its own use or to lease to other colleges. In practice, the completed development accommodates students from St John’s, Lucy Cavendish, and Clare Hall, creating an unusually mixed academic community in a city defined by college distinctiveness.

Allies and Morrison was selected as architect and landscape designer through a design competition in 2020, and drew in their proposals on deep familiarity with Cambridge, and in particular its prior experience of designing college housing over several decades, including the Rosalind Franklin Building for Newnham College (1995), and Cranmer Road, a Passivhaus-certified development for King’s College (2021).

The masterplan is driven by two principal moves: first, the creation of a new pedestrian- priority route, Hinsley Lane, linking Wilberforce Road to the north and Herschel Road to the south; and the arrangement of eight terraces branching off this central spine, each consisting of between four and eight low-energy townhouses. These are interspersed with communal gardens, establishing a rhythm of built form and shared green space.

At its northern threshold from Wilberforce Road, the lane has a distinctly semi-private quality. A broad expanse of reddish gravel gives the impression of a private estate drive more than a street, lending the lane a quiet, internalised character. This might be seen to limit permeability or legibility, but it is successful in evoking the other-worldly, collegiate quality of a place that is inward- looking, self-contained and set apart from the everyday city. That it achieves this while creating a meaningful public connection through the site is to its credit.

Further along, the lane adopts a more mews-like character, flanked by garden walls single-storey, pitched outbuildings, and with slim red pavers underfoot. Car parking is limited and accommodated discreetly in gravel bays alongside the shared surface. Terraces do not front the lane, instead giving onto the green spaces that run between. As a result, the lane is abutted by substantial, three-storey gable ends. This could be overbearing, were it not for the careful detailing of brickwork, chimneys and outbuildings, and the incorporation of gable windows at upper levels. However, the effect is more one of polite detachment than of domesticity. The lane is punctuated by glimpses into shared gardens, whether through metal railings on low brick walls, or through brick archways, which offer a sense of connection and animation.

The orientation of the terraces is a key part of the environmental strategy. Houses are arranged north-south, so that every house benefits from a predominantly south- facing rear elevation. Shading is integrated through bay windows and treillage, while asymmetrical roof pitches, steeper to the north, shallower to the south, allow light to penetrate deeper into the gardens and create a pleasant distinction between fronts and backs.

Linear, communal gardens run between terraces, fronted to the south and backed to the north. Each is anchored by one or more mature trees – oaks, yews, apples and chestnuts – retained from the site’s previous life. These are complemented by simple landscape treatments: bound-gravel paths, swales, timber benches and meadow planting. The result is a landscape of soft edges, more parkland than college court, and an informality that contrasts positively with the buildings.

Beyond the immediate communal gardens, the landscape transitions to looser, more naturalistic areas. The hedgerow that traces the Roman road has been retained and a woodland path now connects to a small copse at the southern end of the site. This hierarchy from formal garden to orchard to woodland creates a remarkable sense of immersion in nature that will clearly be valued by residents.

Households of four-to-seven create groups that are small enough to foster relationships and large enough to offer diversity. Living spaces are bright and well-proportioned, with open-plan kitchens and long dining tables that can seat an entire household in a single sitting.

The houses themselves are deceptively large. Three typologies are deployed: a seven-bedroom house, an accessible six-bedroom end-of-terrace, and a four- bedroom house. The four- and six-bed house types are over three storeys, with the largest units having an additional attic room at third floor. The smaller units were intended to have the capability to accommodate students with families, though they are currently occupied by standard sharers.

Construction-wise, the houses are built from cross-laminated timber (CLT), contributing to a reduced level of embodied carbon, and helping to achieve very high levels of airtightness as low as 0.08 ACH. Oversized brick chimneys offer articulation, while accommodating ventilation infrastructure.

Passivhaus certification was not part of the original brief but was agreed between architect and client during design development. A cost comparison demonstrated that the additional outlay could be offset by increasing capacity, through accommodating an eaves room at second storey. The result is Cambridge’s largest certified Passivhaus scheme to date, with exceptionally low air change rates and U-values. The building fabric includes thermally-broken foundations and brick skins, while orientation, shading, window sizing and ventilation all work hard to balance summer comfort with winter efficiency.

The architectural language is deliberately calm. Materials are drawn from a limited but refined palette: red bricks and red hanging tiles dominate the elevations, complemented by red roof tiles. These are accented by white oriel window surrounds of precast concrete, white metal solar shading, and grey doors and windows with lead-clad dormers. Overall the impression is of measured, well detailed understatement, continuing a thread of quiet, well-proportioned Allies and Morrison schemes across the city.

Internal spaces are bright and well proportioned. Ground floors provide ample living space for large households, with distinct zones for cooking, eating and relaxation, and with neatly accommodated utility rooms at the centre of a deep plan. Finishes are robust and practical, even if carrying a slightly institutional feel – an effect compounded by the self-closing fire doors and automatic lighting. Bedrooms benefit from views to shared gardens and greenery beyond, helping to create a sense of focus and retreat in a household built on sociability.

Perhaps the scheme’s greatest success lies in this attention to sociability. Catering for residents at a stage of life which is uniquely stressful and prone to mental health risks, the design makes a strong case for shared living. Houses of four-to-seven create groups that are small enough to foster relationships and large enough to offer diversity. Living spaces are bright and well-proportioned, with open-plan kitchens and long dining tables that can seat an entire household in a single sitting.

Outside the back door, the terrace itself becomes a secondary community – the equivalent of a staircase in a traditional Cambridge college – unified by a shared decking area that extends along its length. The shared gardens offer a third layer of sociability, providing informal opportunities for encounter, proximity and retreat. Beyond the house itself, terraces form a secondary layer of social identity – akin to a staircase in a vertical hall of residence, and can be an important ready-made social network beyond housemates. The shared garden is a further layer of social connection, providing an alternative form of street and the opportunity for students from different terraces to meet and socialise. As well as the informal support offered by peers, the scheme benefits from its own Porters’ Lodge, a simple, single-storey building at the southern end of the lane, which provides a level of additional support that would usually be reserved for students living within college. Together, these elements strike a careful balance between connectedness and independence that seems well suited for postgraduate residents.

In many ways, Hinsley Lane shies from attention: it is serene and restrained, a place of profound tranquillity, that is somehow set apart from the world. More than anything, it is a place that is tuned to support wellbeing and help students do their best work. But it is also a powerful example of institutional landowners taking a long-term view. As universities grapple with the demands of net zero, student wellbeing, and urban integration, Hinsley Lane offers a quietly persuasive model of how architecture might rise to the challenge.

Credits

Client

St John’s College, Cambridge

Architect

Allies and Morrison

Structural engineer

Smith and Wallwork

MEP (pre-tender), sustainability

Calfordseaden

Fire

The Fire Surgery

Acoustics

Ramboll

Cost

Accertum

Landscape

Allies and Morrison

Project manager

Ridge

Principal designer

Savills

Planning

Shrimplin Planning & Development

Transport

Stantec

Passivhaus

Max Fordham/Allies and Morrison

Ecology

Delta-Simons

Archaeologist

Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Arboriculture

Hayden’s Arboricultural Consultants

Contractor

Cocksedge

MEP subcontractor/ engineer

Munro Building Services

CLT structure

KLH

Brickwork

PMH Brickwork A

Precast concrete

Cambridge Architectural Precast

Metalwork

Solinear

Carpentry

Cocksedge