Jørn Utzon’s Majorca house is among the world’s greatest, says John Pardey

In his new book ’20/20: Twenty Great Houses of the Twentieth Century’ (Lund Humphries, 224pp, £30), architect John Pardey selects and surveys a diverse range of outstanding and influential domestic projects. In this excerpt, he recounts the process by which Jørn Utzon came to build the primal Can Lis on Majorca.

Following his victory in the twentieth-century’s biggest architectural competition for the Sydney Opera House in 1957, nothing was ever going to be the same again for Jørn Utzon and his family. Working from Denmark for a number of years, they finally moved out to Sydney in 1962 and, as a family who had always loved the sea and beach life, found themselves in heaven. Anticipating their move to Australia as permanent, the Utzons bought 2.4 hectares (6 acres) of what at that time was inexpensive seafront land in the Sydney suburb of Bayview Heights. Utzon battled with the planners for nearly two years and produced four schemes before finally achieving consent only months before the Opera House saga reached its tragic climax as a new Government used Utzon as a scapegoat for cost overruns on the previous regime’s flagship project and he and his family were forced to leave Sydney and his unfinished Opera House, never to return. The Bayview site proved to be not only an unfulfilled dream but, in exile, a shrewd if bittersweet investment that sold for a small fortune, the proceeds of which were sufficient to purchase two sites in Majorca.

Jørn and Lis Utzon first visited Majorca in 1957 on a sojourn from their work in Sydney to visit Lis’s mother, and Jørn had designed a small holiday village there for children who had suffered in the post-war polio epidemic. Although the design remained as a series of pencil drawings, the plan, like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, was built around a series of giant rocks and this almost anticipated his later fascination with the stone and rugged terrain of Majorca.

Utzon circa 1960

Visiting again in the late 1960s after their exile from Australia, the Utzons found a landscape and climate that echoed that of New South Wales. While visiting friends in the Migjorn area in the south-east corner of the island, they made a trip out into the countryside and Lis, with her command of several languages, approached a group of three farmers and asked if there was any land for sale. One farmer spoke English and told of three sites: ‘Beautiful, Marvellous and Paradise’.

They promptly bought both ‘Marvellous’ and ‘Paradise’, the first perched on a clifftop just outside the village of Porto Petro, the second on the hills about 10 km (6 miles) inland near the village of S’Horta on the slopes of the mountain beneath an ancient Moorish fort.

It was to be the site on the clifftop that was chosen as their home – the Utzons had always lived by the sea – and the first plans were sketched out in 1970. The house was named Can Lis in honour of Utzon’s wife and they lived there in quiet seclusion for nearly a quarter of a century. They only moved when the glare from the sea became too much for the architect’s sensitive eyes after years of working under an anglepoise lamp (Utzon was rarely seen without a jet-black pair of Raybans to protect his eyes). The rigours of moving from room to room in the outside weather also became more demanding with the passing of the years, especially through the cool winter months. Majorca’s addiction to tourism must have had some part in their decision to eventually leave the house and move up the mountain to ‘Paradise’, as a Club 18–30 holiday camp was developed within earshot and their increasing infamy began to bring tourist coaches, intrepid architecture students and passing glass-bottomed boats whose tour guides would pronounce loudly across the sea that: ‘THIS IS THE HOUSE OF THE ARCHITECT WHO DESIGNED THE SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE’.

The Bayview house designs in Sydney were where the language of the Majorcan houses was worked out – an architectural vocabulary of courts and linked elements that began with his first house in Hellebøk. This had begun the theme of a house sheltering behind a wall, yet it was his fascination with the courtyard houses of ancient China and north Africa that provided the real inspiration for this otherworldliness of the house behind, or within, a wall. Utzon visited the site on the clifftop before the house was built and climbed down the ledges of the cliff to sit in a cave almost directly below and enjoy the absolute unity of place and view, of shelter and exposure, and this became the feeling he wanted to recreate in his new home.

The first plan for the houses is dated November 1970 and it is named as ‘Casa Olicia’. It takes the theme of the Bayview designs but distributes three blocks along a linear court nestling behind an unbroken wall, save the entrance off Calle de la Media Luna (Half-Moon Street). The key elements are already in place in embryonic form – the defensive wall, the colonnaded, stoa-like court opening out to the sea, the angled living room replete with funnel-shaped window bays, and cave-like bedrooms with cradled bed spaces and further projecting bays. Perhaps the most striking aspect of this design is the openness of the composition, with the whole plan spread-eagled around the single entrance court like two hands spread towards the African coast beyond the horizon.

View from the cave below Can Lis, which provided inspiration for the house

The final plan was initially modelled by Utzon in sugar cubes, and then drawn for the authorities by his son Jan and adjusted, fine-tuned and created by the masons and Utzon himself in situ. The house has the appearance of a beautifully crafted work of geometry, something classical that fell from the skies and crashed onto the stone platform of the clifftop to adjust itself to the nature of the place. Utzon liked to say, with extraordinary understatement, that it was all so simple, “no more than the way birds know instinctively where to nest on a cliff-top”. The house, almost a small village in stone, seems as if it has been there for centuries, yet it also feels so unique and new.

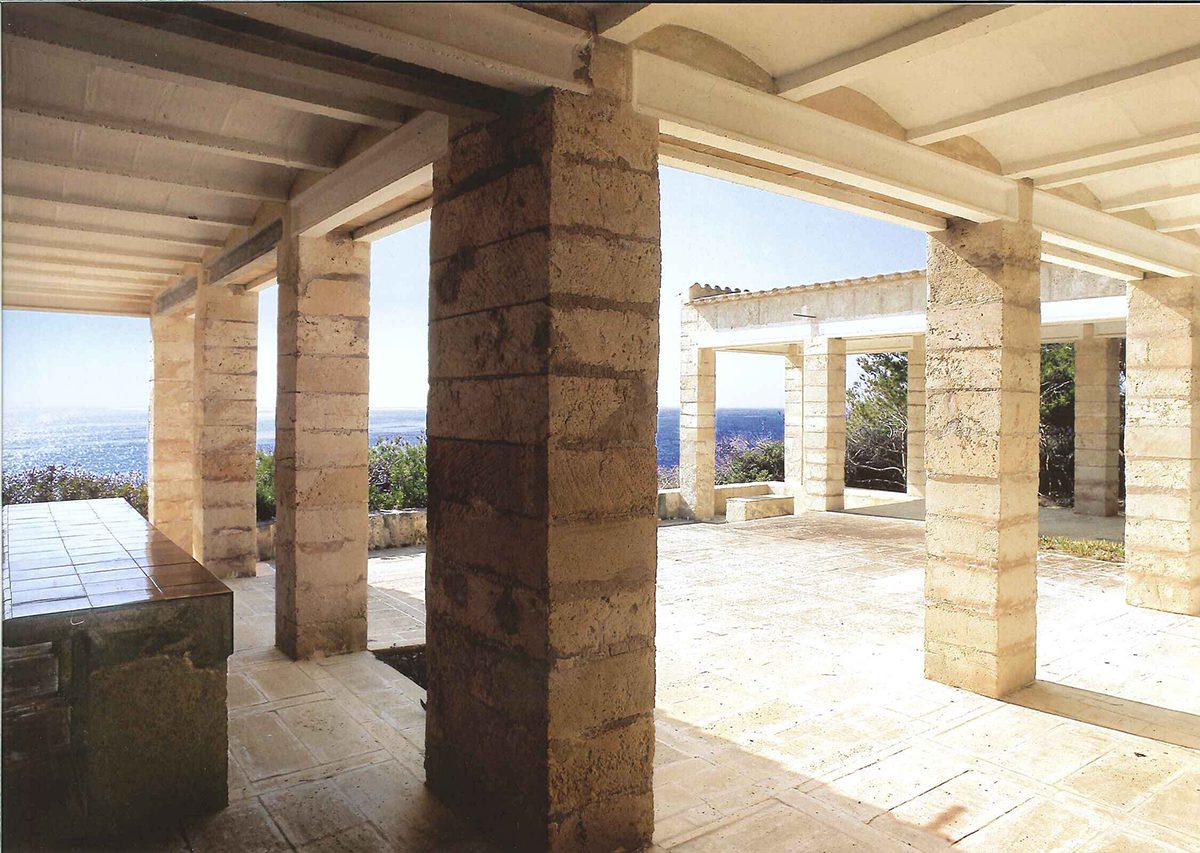

Arriving on a scruffy road with houses dotted along one side among thick scrub, there is no hint of the sea –or that a cliff edge is only some 20 metres away. It is easy to pass Can Lis unnoticed, for its street facade is less than low-key – little more than a series of walls. Only the glazed tiled bench sitting beneath a rudimentary porch, with its blank, grainy wooden door, hints at a domestic world beyond. A crescent-shaped incision in the wall offers the first tantalising glimpse of the ocean beyond. This moment is twinned with a realisation that two open spaces await either side. The crescent, framed in dark blue and white glazed geometric tiles, points left but the overwhelming pull is right, into a nine-square courtyard framed by stoa-like colonnades that open out to the sea.

The courtyard is surprisingly small, intimate even, but this quality is immediately juxtaposed by the vastness of the sea, the sky and their meeting at the horizon. This courtyard is the anchor to the house – a house that reveals itself to be a chain of five blocks – and sits square to the cliff-face some 30 degrees east of due south. It immediately brings to mind ancient Greece with its colonnades and stoas and this is fused with the generosity and heroic nature of opening onto the sea, something that echoes in miniature Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute court in California, which faces the Pacific, half a world away. This courtyard leaves no doubt that the house is dedicated to nature – to the path of the sun across the sky above the sea.

To the rear of the court lies the fairly rudimentary kitchen occupying two square bays divided into pantry and cooking areas with all the kitchen furniture built in thin stone slabs with white tiled surfaces. Shuttered windows open out onto the street beyond. A further two bays form a dining space with a built-in pine bench around a large table and two large window bays that project out beneath the colonnade roof; a final bay forms a small store. Each space is modest and possesses a raw domestic quality – no formica, stainless steel or kitchen gadgets here – that gives a sense of outdoor living, and an earthy natural life. The only hint of sophistication is the aluminium light fitting running across the back wall of the dining space, but yet again this is brought down to earth by the bare light bulbs plugged in like rivets.

Utzon’s lifelong interest in the way nature constructs itself and his development of an ‘additive architecture’ is the basis for the construction of the house. The kit of parts – stone blocks, concrete ‘I’ beams and curved tiles – provides not just a dimensional logic, but a constructional DNA that grows the building into a unified whole. Horizontal structure is founded on standard precast concrete ‘I’ beams that can span up to about 5 metres, and these are used singly as supports for roof structures and doubled up as lintels for wall supports. Utzon recalled how he noticed the arched clay tiles in a local baker’s shop one morning and knew that was what the roofs at Can Lis, then under construction, had to be. These bovedillas, once common in the region, had in fact ceased to be produced some years earlier, but Utzon’s master builder knew where these were once made so they returned to the works, found the original wooden curved moulds and set about making them. The tiles are made from flat clay slabs that are placed wet onto the mould where they quickly slump and assume the curved profile; these are then slid off to rest on their edges and dry in the sun. In this way, Utzon rediscovered and revived a small fragment of Majorcan vernacular: the tiles are still in manufacture today. Each bovedilla is placed between the flanges of the spanning ‘I’ beam, covered with flat clay tiles and finished in waterproof quarry tiles. These mini-vaults are appropriate to an architect who so frequently saw the roof as a cloud floating above space – from the rolling trade-wind clouds of his Bagsværd Church to the epic vaults of the Opera House – and the Majorcan houses possess the same idea in the most understated, yet powerful, way.

Utzon’s inventiveness in using locally sourced, humble materials is part of the magic of Can Lis and is consistent with all of his work, where a kit of parts, or the standard elements of an additive architecture, combine to make forms as diverse as a bench or a shell spanning the Opera House. The sandstone blocks, quarried in nearby Salinas, are common in that corner of Majorca and have been used for generations for building even the most humble of farm buildings and field walls, although the quarry is now depleted and shut down. The same stone was also once used to build the cathedral in Palma de Mallorca. This marés stone has a golden, buttery colour and a sandy texture, and was cut out of the quarry by a giant circular saw that first cut a chequerboard of incisions down into the bed; a horizontal cut then yielded the blocks like sugar cubes. The concentric circular saw-marks on the stone surface evoke the circular motifs of the Opera House shell drawings, give life to the inert material and hint that this may be a living thing, like a tree cut down with its grain revealed on the surface. A different, harder stone from a quarry in Santanyi some 6 km (4 miles) away, cut in the same sizes, was used for floor surfaces and this has a smoother, denser texture and a light grey colour that absorbs any reflected glare from the sun.

Beneath one colonnade of the open court, a stone and glazed tiled bench and dining table are built-in, as if fossilised. To the front, two steps drop towards the cliff edge with a low, stone wall and a single stone slab that lies like a segment of a fallen column, given use as a table by a glazed brown tiled surface. A small enigmatic court lies alongside the main courtyard, enclosed by high walls yet opened up by semi-circular apertures (Utzon liked to describe the effect of the main semicircular cut-out and the horizon beyond as like a full wine glass). The court is empty save a stone-built, glazed tiled, semicircular table that suggests dining, but there are no seats, so with a single dark blue tile on the table’s rim, this suddenly becomes a compass pointing due south. This is the full stop to the ensemble of buildings that make Can Lis and has a strange, temple-like, still atmosphere, with curved shadows that attempt to join up to form a circle on the floor and hint back to the crescent at the entrance. For Utzon, this idea comes directly from the traditional Danish farmhouse where an open garden space, a vinterhave, provides a place to sit and work with plants, so placed to admit the sun in winter but remain shaded in summer.

While the courtyard of Can Lis opens out to the sea, the living room seems to fold in and make an intense union of place and horizon. Entered from a shaded courtyard furnished with built-in seats and planters, through a fourbayed colonnade, the living room is essentially a cubic volume some 4.5 metres squared, but a single column with lintels above articulates this space, defining the route into the room. The surprise of entering a tall space combines with the even light without glare and an intense silence. The view through the different sized, deep bays is brought sharply into focus and the segments of a single horizon are the invitation to sit down on the semicircular seat to watch the drama that nature plays out. The plan, with the five deep, tapering windows like fingers stretching out to the ocean, has an uncanny similarity to Andrea Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza, with its five diminishing openings focused onto the semicircular auditorium seats. Utzon related how the deep reveals of the palace at Versailles were an influence, whilst other references, from thick-walled vernacular buildings to the splayed openings in Corbusier’s Ronchamp chapel, abound. These extraordinary stone eyes onto the ocean, however, really have no like, but are part of the inventiveness of an architect at the height of his powers. The fact that one can actually inhabit these funnels, like personal chapels off a nave, adds to their presence. This intensity is further enhanced by the fact that there is no window – no frames or shadows – only glass held in frames placed on the outside of the walls, influenced by the empty apertures of Sigurd Lewerentz’s St Mark’s Church in Björkhagen, completed two years earlier.

It is not just the deep bays that form the windowless windows, but the outer sheltering structure, a kind of loggia that provides shade that prevents glare from the glass, rendering it invisible. This outer architecture is reminiscent of Kahn ‘wrapping ruins’ around his buildings, a style that he developed initially in his project for an embassy in Luanda, Angola. Kahn wrote that “I am doing a building in Africa, which is very close to the equator. The glare is killing. Everybody looks black against the sunlight . . . So therefore I thought of the beauty of ruins . . . and so I thought of wrapping ruins around buildings: you might say encasing a building in a ruin so that you look through the wall which has its apertures as if by accident . . . I felt this would be an answer to the glare problem”.

The twin phenomenon of the sea and the horizon being sucked into the room is magically balanced by the impression of being fired out simultaneously through the five apertures. Central to this drama is the not quite semicircular stone-built seat, furnished with dark blue tiles and crisp white linen cushions, that sits not quite square to the room but shifted to orient due south and is complemented by a segmented arc of table that was the family’s auditorium to nature. High up on the west wall is a slit window, with the glass simply bonded to the outside wall as Utzon had so admired in Lewerentz’s chapel at Klippan in Sweden, that lets the sun kiss the stone in a blaze of light just before evening each day. It is this small touch that makes the living room at Can Lis an absolutely unforgettable, timeless experience. Externally, the drama is hidden beneath the sheltering portico that shades the windows and lends a static, temple-like quality – even the slit that has such an impact internally is mute – only the twin Catalan triangular chimneys, so typical of Majorcan village houses, draw the eye.

The journey from building to building continues from the shaded court at the back of the living block, across stepping stones and past a twisted tree to enter a further court, this one with no stone-built furniture, only planting and a single doorway into what becomes two bedrooms, paired around a central covered patio. Each is entered by a shared lobby with a small utilitarian bathroom and each is expressed as a separate volume with a pair of stone-eyed bay windows, miniature versions of those in the living room scaled to suit the reclining viewer in the built-in bed alcove, replete with cellular stone book recesses and fronted by a small glazed tiled table. These rooms find union in the central patio. Leaving the bedroom court, one last step across a small divide brings you through a doorway into the final covered patio, where the stone-built furniture reappears in blue and white diagonal glazed tiles. This leads into a small lobby, with a bathroom, and then into the last guest bedroom.

Throughout, door and shutter frames are visibly fixed to one face of the stone apertures and the doors themselves made in boards held in place by neat rows of exposed nail heads; the stone jambs are neatly carved out with elliptical incisions that allow space for the door handles and surprisingly bring to mind Michelangelo’s handrail detail on the Laurentian library stairs.

A love of glazed tiles is quite particular to Utzon. The tiled domes and faceted vaults in Islamic architecture provided direct inspiration for the shells of the Opera House, but it was the idea of placing glazed and matt tiles together with the logic that only the matt tiles were to be cut that created the iridescence that helped make the Opera House so memorable. At Can Lis the entrance is marked by a stone-built, glazed tiled bench – white and dark blue coloured tiles. This welcoming gesture is typical of Islamic and Mediterranean traditional dwellings, where social life abounds, immediately outside the front door. These tiles are also used for the internal built-in furniture, but external benches within the courts use tan coloured tiles, with either dark blue or white edges or cut patterns.

It now seems hard to imagine why the Utzons should have left this house, yet with the passing of the years their other site, ‘Paradise’, high up the mountainside behind the coastline, called and in 1994 they moved to their new home, Can Feliz, leaving Can Lis to their now grown-up family. Can Lis must be the least-visited and known of all the great houses of the twentieth century and, like Utzon himself, this withdrawal from the world has lent an enigmatic quality that merely increases the interest and notoriety of both.