Witherford Watson Mann’s carefully considered addition to the second oldest college at Cambridge delicately improves access to the college and adds a new riverfront café.

Brick walls were bowing, circulation was convoluted and, in the event of a fire – well, best not to think about that. Clare College at Cambridge is old, the second oldest at the university in fact, being founded in 1326 – and its age was becoming alarmingly apparent.

To put in perspective the history of its physical construction, work on the building that exists mostly today had to be stopped during the 1600s due to the civil war – resulting in curious combination of gothic and English classical styles. It’s rumoured, too, that the building was spared complete destruction as Cromwell garrisoned soldiers there.

All of this means that, until recently, the building was falling apart. But some architects, thankfully, are a dab hand at taking care of such buildings, namely, Witherford Watson Mann, as evidenced here in Cambridge.

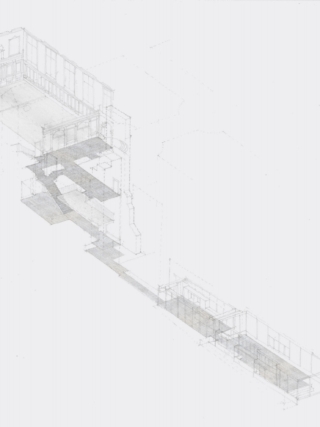

Ground floor plan of Clare College’s Old Court. There River Room can be seen as part of the wedge of land that protrudes along the boundary towards the northwest up to the River Cam.

Showing AT around the college, director Stephen Witherford referred to the practice’s work at Astley Castle. The Stirling Prize-winning project was the site where the studio honed an approach to dealing with crumbling, ancient buildings – putting their decaying space to effective use. “It’s the sense of amplifying the qualities of what was already there with new architecture,” said Witherford describing the work at Clare College’s Old Court.

Here, “the brief was a collage of the department’s practical problems,” aka, bringing means of escape up to speed with fire safety standards, improving access to the college, as well as adding a new café.

Work began in 2014 when the practice won an invited competition run by the college. The studio explored numerous options, after a year of “removing and revealing” (the Old Court’s north wall took a year to mend) and adjusting what it had proposed, before settling on a site known as the North Passage. This wedge of land spans 120 metres, tapering out from one metre wide along Trinity Lane to eight metres wide beside the River Cam, looking out over the river and onto gardens beyond.

View out to the River Room’s cafe seating area which looks out over the River Cam.

Within this wedge lies the new River Room, which hosts a new café and workspace for students. An oak glulam timber frame forms its structure, part of a much more complicated structural timber skeleton that stretches back into the College’s Old Court building and up into the Court’s inner workings. Such was the complexity of this, that a temporary bridge across the Cam had to be built to transport materials. The meticulous work of contractor Barnes Construction meant that the timber “animal” (as Witherford describes it) could, in theory, be taken away if needed.

The pieces of this giant 3-D wooden jigsaw come from Barnsley, South Yorkshire, made by Constructional Timber who, with incredible precision, pre-planned every timber joint, with each detail and connection being individually drawn by structural engineers Smith and Wallwork.

The room is also used by students to work in, as well. Though small, the room is able to cater for individuals and larger groups. “It’s about giving students a variety of spaces to work,” Witherford told AT. “They’ve had lockdown, students don’t want to be stuck in their rooms.”

A model of the timber structure that traverses through the college. (Credit David Grandorge)

The River Room has also been set up acoustically to be able to be used for music recitals as well as weddings and other functions. But while it’s most spatially significant part of the project, it’s also the most well-hidden. You’d be forgiven, upon initially clicking to read this article, for not knowing of a river-front café, for it snakes it way along Clare College’s medieval boundary line to the water, tucked behind a wall.

The money shot for this project, viewed from the neighbouring Trinity College, instead draws attention to perhaps what might be considered the more mundane programmatic aspects of the project: a glazed gallery that connects a lift, the Senior Combination Room and a fire escape.

But mundane it is certainly not. For starters, this might be the finest fire escape stair in the land. (You’d maybe hope so for a £42 million project). What better means of safe egress than via beautifully crafted oak timber that spirals down to the ground? The glazed link is essentially a corridor to the brick-encased lift and means the north wall of the Senior Combination Room is no longer exposed to the elements. A picture has in fact been put on it since the link was built and the contrast between what’s old and new is immediately apparent, but not a point that’s made with overbearing aplomb, with the qualities of light and a view out to the gardens of Trinity College being what defines the space.

From an external perspective, the language of Witherford Watson Mann’s work is mostly brick, with timber being secondary. Inside, this is reversed, while new materials such as Purbeck stone and pigmented pre-cast concrete have been introduced as well. Working with conservation architect Freeland Rees Roberts, the former comes from Dorset and has been used to replace the floor for the main entrance – replacing concrete slabs that came before, bringing the main entrance of the college to be more visually in line with the stone originally used elsewhere in the college.

This stonework – that Witherford is proud to state “has lots of shell in it” (in line with the ethos of being able to “see history”) – knits the college together as the project eases connections to the college’s buttery and beyond, defining improved routes through for students taking food to the dining hall. At the project’s base, inside, it acts as feet to the glulam timber posts, to aid staffers with mopping and cleaning. “Lots of buildings get cut off at their feet,” said Witherford. “We we’re trying to see how this building lands.”

Metal guarding protects some the Purbeck stone-footed timber posts from being knocked by food trolleys passing through.

The pigmented pre-cast concrete, meanwhile, strives to match in colour the traditional Ketton stone used throughout the college’s original structure, typically for archways. The new concrete has been used to encase other thresholds, acting as a mediator between the original brickwork and newer elements – employing salvaged Ketton stone would’ve looked messy, says Witherford. Other architectural details, such as a mini trough in the Purbeck stone between it at the original brick, provides visual tolerance between the old and new. The ‘new’ is also literally hidden within the old as well, as can be seen with new stone stairs at the college’s main entrance, that retract to form a lift for those with mobility requirements. But while a clever way to maintain the original look of the entrance, the process is rather slow and cumbersome. A simple ramp would suffice.

“We didn’t want Old Court to become a museum piece,” Deborah Hoy, estate director at Clare College told AT. “It had to remain the beating heart of the college.”

When being shown the project during a lunch period, it was clear to see the River Room in particular enjoying immediate success and popularity. Interestingly, the room was serving as a means to democratise space within the college, too: college staff were happily eating here alongside students – something which is a rarity across UK universities. And already, students have asked the college for the space to be open for longer so they can work there beyond its original open hours of 9am-6pm, with the college looking to make it open 24/7.

Credits

Client

Clare College

Architect

Witherford Watson Mann

Conservation architect

Freeland Rees Roberts

Historic buildings advisor

Dr Roland Harris

Main contractor

Barnes Construction Ltd

Structural and civil engineer

Smith & Wallwork

Acoustics and services engineer

Max Fordham

Quantity surveyor and project management

Henry Riley

Landscape architects

Liz Lake Associates

Fire consultants

The Fire Surgery

Planning consultant

Turley

Oak glulam frame

Constructional Timber

Purbeck stone floor

Stonebuild

Oak staircase

Lowe & Simpson

Pre-cast concrete

Cambridge Architectural Precast

Brickwork

Anglian Brickwork