AT chats to Duarte Lobo Antunes and Jack Taylor from A is for Architecture about their Folkestone Harbour Plan which has recently been granted planning permission.

Can you start by giving us some background on A is For Architecture?

We’ve all come from fairly international backgrounds; Portuguese, British, Swiss-trained. In a way, we’re children of the pre-Brexit era, shaped by that openness and exchange.

Even though we’re a small office, we’ve often worked on large-scale masterplans and urban projects. We’ve always resisted the idea that smaller, younger practices are only brought in for “community add-ons”, like a bench here, a colourful intervention there. We believe small practices can, and should, play meaningful roles in major developments.

You’ve always thought a lot about the idea of the coastal town and have mentioned how Britain’s coastal towns vary from the European picture. Can you explain this?

We often talk about the “coastal paradox.” In many countries, the coast is traditionally the wealthiest part of the country. But in Britain, some of the most deprived communities are coastal. It’s sad, but it also presents opportunities. There are lots of reasons why this is the case. Industrial decline is one of them, but inland cities like Birmingham or Leicester developed as industrial hubs, while coastal towns were sometimes seen as exposed, vulnerable places to settle. Later, the decline of ferry connections and seaside tourism compounded things.

These places are also now on the frontline of the climate crisis with storms, erosion, sea levels rising, so they demand new forms of investment and adaptation. And with remote working, people are increasingly drawn to living by the coast: somewhere that combines cultural life with expansive landscapes. Folkestone is a great example: you get food, art, sport, and community, alongside great landscapes and sea air!

So you see coastal regeneration as both an architectural and social opportunity?

Exactly. As architects we can help coastal communities respond to climate change, housing needs, and cultural reinvention. At the same time, the coast allows for things that are culturally “exceptional.” Think of piers, rollercoasters, pleasure gardens. It’s where Britain has historically allowed itself to be a bit weird, playful, even outrageous.

That sense of cultural looseness opens coastal towns up for exciting change. If you tried to design a sober, brick-grid London-style development in Folkestone, it would feel completely out of place. The coast demands something more adventurous, but always contextually specific.

Could you talk us through the background to the Folkestone Harbour site?

Around the early 2000s, the harbour was in decline. The amusement park had closed. The ferry terminal was defunct. The station was no longer in use. The whole seafront was shut off from the public. Sir Roger De Haan, who used to own Saga and is from Folkestone, bought the seafront outright. I mean, it’s extraordinary that an individual could do that, but it gave him the leverage to try and revitalise the town. At first, the idea was to bring a university campus here, under a Norman Foster masterplan. That didn’t materialise. In the meantime, De Haan invested in local schools, supported the Creative Quarter and the Folkestone Triennial, and then eventually turned focus back to the seafront.

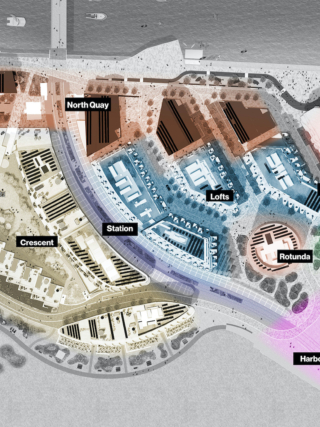

There was a Farrells masterplan for up to a thousand homes — a more conventional urban grid that altered much of the site’s heritage, including the station. Later, at ACME, we reworked the masterplan into a series of “inverted crescents” to maximise sea views and bring public space closer to the shingle beach. That’s the version we inherited when we set up our own practice.

What kind of constraints did you inherit, and how did you respond?

We were working within an outline planning consent so there were fixed parameters: maximum and minimum building heights, and a required number of units (around 800 across our three plots, half the total). We couldn’t just decide to build townhouses or cut the density.

So our task was to reinvent these plots as a distinct piece of urban design: what we called a “Harbourplan” within the larger masterplan. We prioritised permeability, public space, and connections to the Old Town. We fought against podium developments and instead created a network of streets and squares. We also did detailed work on wind, views, and massing very early on. The south-westerlies are strong, so we ran CFD analysis and wind tunnel testing to ensure the blocks created sheltered, comfortable streets.

And your approach to the architecture itself?

Always through context. We analysed geometries from the harbour, cliffs, and rail infrastructure, and translated those into forms. We looked at local material palettes: Folkestone has both red-brick and painted-white traditions, and the harbour itself has strong primary colours. Our facades pick up on that.

Some of the designs felt risky, like the seafront townhouses with big projecting balconies, interestingly those are now some of the features people love the most.

What kind of feedback have you got from locals?

In Folkestone, nostalgia seems to be very powerful. Some older residents asked why we couldn’t just bring back the boating pond or the amusement arcade of their childhood. But those things won’t return in the same way. Nostalgia is part of the cultural psyche of the coast, but it can also hold meaningful regeneration back.

Was there pushback on affordable housing?

Yes, and it’s a complicated issue. The outline consent, agreed in 2015, fixed the affordable housing percentage at around 8 – 13%. It’s low, but waterfront sites are expensive and technically complex to build on, and the Section 106 agreement required the developer to deliver sea defences, flood protection, and beach replenishment as part of the development. While these interventions will majorly benefit the whole town and are much needed, it inevitably impacted the quota of affordable units.

We’d love to see councils take more of a role in delivering affordable housing directly, as happens in parts of Europe, rather than putting so much responsibility onto private developers.

Your work feels quite European in character. Where does that come from?

Our backgrounds, certainly as we’ve all studied and worked abroad. We’re used to looking outward, drawing on precedents from Hamburg, Copenhagen, Aarhus. We took the whole office to Denmark for five days, walking around every new harbour development we could.

Whilst these aren’t models to necessarily copy, they prove that ambitious, design-led coastal regeneration is possible, at the same time as retaining a place’s specific cultural identity.

In the UK, there’s often a suspicion of “grand plans” and a preference for development to be more patchwork. But to bring long-lasting transformation for Folkestone, we needed an ambitious vision.

Where does the Folkestone project go from here?

We’re now working on the next phase, Plot C1, which will start on site next year. Altogether, it’s years of work still ahead. We’ve already spent almost four years dedicated to just three plots. It’s unique for a small practice like ours to be entrusted with something of this scale.

We want the scheme to reconnect the town with the sea, to create a genuinely public waterfront, and give Folkestone a future beyond nostalgia. The harbour shouldn’t replace the town centre, it’s a destination, not a centre, but it can complement and strengthen the whole town.

More broadly, we hope it demonstrates that coastal regeneration can be ambitious, contextual, and design-led. The coast is full of potential. It’s where Britain has always experimented culturally, and it can be a frontier for addressing the challenges of climate, housing, and identity today.

Carmo Montalvão is an Associate Director at A is for Architecture, and is part of the team working on the Folkestone Harbour plan with Jack and Duarte.