Dirk Somers of Belgian practice Bovenbouw talks to Louis Mayes about the role of drawing, and the importance of viewing a sketch as a problem for discussion as much as a solution

“Sometimes the sketch in architectural culture is put on a podium, and it has this macho aura of Niemeyer – one line that changes the world. I think it’s a bit stupid,” says Dirk Somers, the director of Bovenbouw. He is scathing about the tendency to post-rationalise and justify work through sketches, arguing that it contributes to “the myth of the architect” when in fact “the process is never that smooth.”

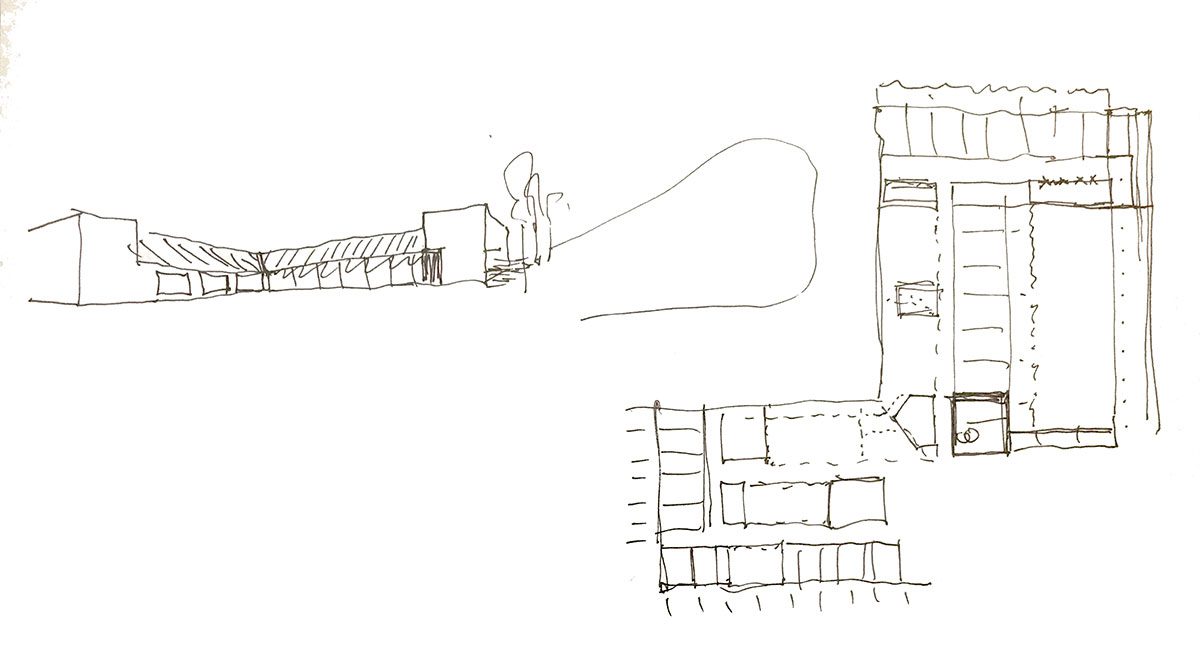

Instead, the sketch is used as a rapid and informal tool for communicating within the practice. “It’s just the fastest way to study and clarify and communicate things. Somehow the sketch has this power of just framing what is essential.” Looking at Bovenbouw’s sketches, there are often notes, question marks, jokes – a frozen moment within the design process that suggests this drawing is the manifestation of a previous conversation. Materials are demarcated through annotations. A dotted line suggests an alternative train of thought, where the plan has been draped alongside the elevation. Once discussed, the sketch is often discarded.

Punctuation marks suggest collaboration – question and exclamation marks relate to queries and provocations. As Somers explains, “I never feel that something is decided with a sketch – I always feel it’s something I like people to try. It’s not a prescription – more a vehicle to explain or suggest an idea.” The ambiguity inherent to the sketch, and the lack of definition, allows for interpretation within the design team. This couldn’t have been achieved with the tolerance associated with a physical model or computer drawing, or as Somers puts it “it’s fundamental that the sketch is as much a problem as a solution.”

“In an office it’s important to offer space for everyone involved to be involved with the conclusion. I generally feel that I don’t need to provide the solution, I need to provide a certain scope, and the solution can be decided upon by someone else,” says Somers. “The step from inaccurate sketch to accurate drawing also allows people to get involved with the final solution.” In this way, the practice allows all parties to contribute to the output.

Noticeably, the majority of the sketches we look at are conveyed in three dimensions. “It’s important to make design decisions in perspective – it helps you consider design decisions more.” Drawn quickly, the images aren’t precious – but convey the information effectively. “I think you only really acquire it over many years. Only in the last ten years have I felt less ashamed of my drawings,” Somers admits. The value of these sketches lies not in the aesthetics, but in how they convey information. Somers bemoans how it is only in practice that you really start to sketch, and explains the difference drawing as something you do on a study trip to creating a sketch in practice. “A student’s sketch is often too considered – you can’t fake the spontaneity of a sketch.”

In this way the sketch remains an honest and unpretentious tool to develop ideas and record the design process. “Every medium has its reason for existence. This differs from person to person, but to me the sketch is super-fast and super focused and also something which passes quickly in the digital world. This is what it means to our practice.” This differs from some other practices, where there is an onus placed on a sketch as a presentation piece more than a working drawing.

“The sketch is only a step,” explains Somers. An important one, but one that remains honest and contributes to the design as a whole. This culture of exchanging drawings within the office allows Somers to steer the focus of the design team, but not to define the scope – the sketch remains a vehicle that maintains discussion during the design process.