Bovenbouw Architectuur and David Kohn Architects have remodelled an 18th-century Flemish religious community complex into the University of Hasselt’s architecture faculty and a new public space.

A new circular opening in the northern perimeter wall increases permeability, connecting the site with the public library and Hasselt University’s Faculty of Law.

Although the history of the beguines in Hasselt, Belgium, stretches back to the 13th century, the present-day beguinage has its origin in 1707. The beguine houses, each with a modest front garden opening towards the central square, once formed a carefully secluded ensemble, with a church as its spatial and spiritual centre. The beguines were unmarried or widowed women who chose a life dedicated to God without the rigid vows of a monastic order. Hence, beguine communities were not so much an ‘order’ but rather a social and spiritual ‘movement’, with remarkable diversity and lasting impact on both society and urban form. These women lived in self-sufficient communities, engaging in manual labour, craft and caregiving, while cultivating a religious rhythm of daily life. The typology of the beguinage, an enclosed community designed to meet both spiritual and material needs, endures as an urban trace of collective living that resonates to this day.

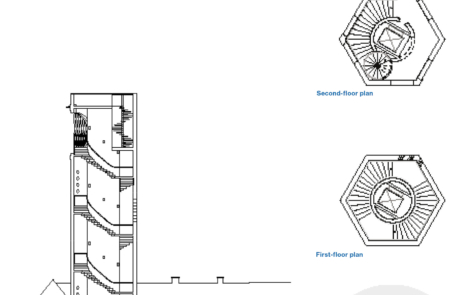

A new tower – a hexagonal structure in brick, standing 30-metres tall – re-establishes the beguinage as a vertical marker in the city’s skyline, signalling the presence of the university.

During the Napoleonic era, the beguines were expelled, and their site was secularised. The Second World War dealt another heavy blow: Allied bombing destroyed the church and several houses. Particularly, the north- western part of the beguinage – the oldest part – was damaged beyond repair, fracturing its secluded character. What remained was restored according to the principles of stylistic restoration, in which fragments and historic details from other buildings were integrated into the historised interiors. At this time, the beguine houses were adapted to be reused as a public library. The ruined church was left as a romantic folly in the landscape, and the central square was transformed into a public garden.

In 1958, a modern exhibition building arose on the site, its sharp contrast in style and scale underscoring the tension between old and new. When the library eventually moved to a Modernist building in the late 1970s, the beguine houses were integrated into a centre for contemporary art located in the 1958 pavilion – today known as Z33. Between 2011 and 2019, the Italian architect Francesca Torzo remodelled the pavilion and designed a new wing, completing the perimeter of the beguinage garden and reaffirming its enclosure. To the north, the beguinage adjoins a former gin distillery – protected as heritage in the 1970s and later converted into a museum – an industrial neighbour that, though not originally part of the beguine domain, now enriches the site’s layered history.

With Torzo’s new wing in place, the beguine houses and the gatehouse, once used by Z33, found themselves without a clear purpose. The public owner of the site therefore decided to put them on the market, inviting private developers to present both offers and visions for their reuse. Yet the decision to sell and privatise the beguinage sparked an immediate and fervent public debate. A petition, initiated by students of the architecture faculty of the university, argued passionately for safeguarding the beguinage’s public and common character, and against private development and densification of the site. The intensity of the debate resulted in no private parties entering bids. Instead, Hasselt University stepped forward, expressing its intention to invest in the beguinage as a new campus, in particular as an extension of its architectural faculty. Hence, the project was shaped by a tripartite collaboration: the Province of Limburg, owner of the buildings; the City of Hasselt, owner of the park; and Hasselt University, which would inhabit the site through a 50-year lease.

Historic details have been reinterpreted or repaired. New elements have been designed as playful echoes of historic details, producing an interior ensemble that feels at once rooted and renewed.

Via the Open Call procedure, the Flemish Government Architect launched a competition. Four design teams were selected to enter a proposal. The competition was ultimately won by Bovenbouw and David Kohn Architects. Their proposal addressed the imbalance caused by the post-war destruction and later interventions by introducing a new tower and reinforcing the presence of the central ruin. Crucially, theirs was the only scheme that preserved the ruin as an open, public space, adding only a light programme to enhance its usability.

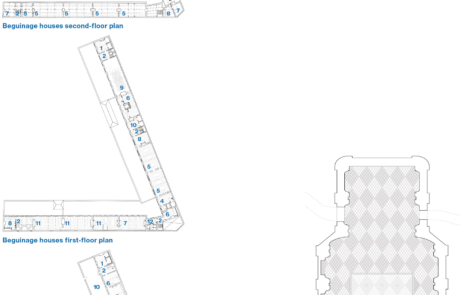

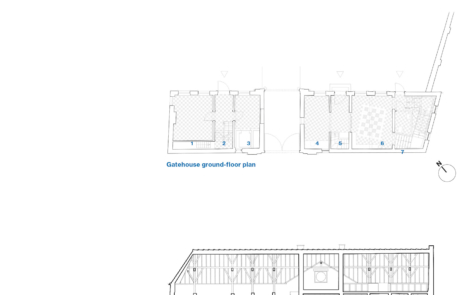

The beguine houses had originally functioned as individual dwellings, each with its own internal stair and each with access from a small front garden to the central churchyard. In the 1950s renovation, the houses were pierced with connecting openings, creating an enfilade that facilitated circulation and supported their reuse as a library. Their adaptation as exhibition spaces in the 1980s brought further alterations, including the removal of floors to create double-height galleries. Today, the south-east wing of the houses accommodates researchers’ offices on the ground and first floors, while the north-east wing contains a reception space, an urban lab, and exhibition rooms on the ground floor, with a lecture hall and classroom above. To accommodate this new use, the architects restored the original domestic scale of the houses, reconstructing missing floors and reinstating the rhythm of rooms. The horizontal enfilade still connects the houses, though now by means of discreet openings that blend into the wall surfaces, allowing the historic layout to assert itself once more.

Where possible, historic details were carefully repaired or reinterpreted: mantelpieces, floor tiles, wainscoting, and historic windows – some with coloured stained-glass elements – lending each room a distinctive character. Because the beguinage is protected heritage, every intervention required careful review by the Flanders Heritage Agency. Yet given that many apparently historic elements dated only from post-war restoration, not every surface or feature was untouchable. This paradox granted the architects a degree of freedom, though they approached it with delicacy.

Authentic interior elements were retained and reused wherever possible. New details, meanwhile, were designed as sensitive echoes of the historic ones, producing an interior ensemble that feels at once rooted and renewed. This playful reinterpretation of historic interior elements is reminiscent of Bovenbouw’s refurbishment of three historic houses in Antwerp into apartments, which was completed in 2016. However, according to heritage regulations, some elements needed a more accurate restoration, such as the wooden staircases and bannisters, in which degraded pieces were carefully copied and reintegrated, leading to a beautiful patchwork of old and new wood.

The attics of the beguine houses have been transformed into teaching studios, with dormer windows set between existing timber trusses, flooding the spaces with daylight.

The attics of the beguine houses have been transformed into teaching studios for architecture students. Large dormer windows, precisely set between the existing timber trusses, flood the spaces with daylight and open panoramic views across the beguinage garden, with its ruin, tower, and Z33 buildings. In one of the outer houses, four guest rooms share a communal kitchen. Here too, fragments of historic detail – such as repurposed wainscoting – have been used inventively to form box beds and bathroom doors.

The renovated beguine houses, with their front doors and house numbers, creaking stairs and intimate rooms, have a domestic atmosphere. The gatehouse, renovated by the same design team, has been given a more public vocation, housing an auditorium and a soon-to-open permanent exhibition dedicated to the history of the beguinage designed by Voet Architectuur.

Drawing inspiration from Nikolaus Pevsner’s planning theories as set out in his book Visual Planning and the Picturesque, the architects structured the garden around two focal points: the church ruins and the newly built tower. David Kohn Architects had already experimented with picturesque planning to define the layout of New College in Oxford, a project it delivered around the same time as the Hasselt beguinage. This approach seems to be especially well-suited to the uniquely layered historic fabric of the beguinage. The ruin’s asymmetrical form, the tower, the meandering paths amid the flower beds and old and new trees, and the garden walls with doors providing views of the front gardens of the houses unfold like a sequence of views rather than fixed compositions.

Heritage regulations called for accurate restoration of wooden staircases and bannisters. Degraded elements have been carefully copied and reintegrated, creating a patchwork of old and new wood.

Following the wartime bombing, only a fragment of the church survived – the south-eastern façade and its adjoining spiral staircase tower. In an effort to stabilise these remains, the ruins were dismantled to below window height, and their exposed edges topped with a protective plaster. Over subsequent decades, the ruin became shrouded in ivy and other plants, acquiring the picturesque aspect of a folly within the park. As part of the new project, this ruin was carefully restored. Vegetation was removed, and the masonry consolidated. The old south-east wall was repaired with a local stone that matched the original. The lost outlines of the missing façades were evoked by new, low-wall segments in darker, smoother brick walls varying from approximately one to two metres in height with integrated benches.

These gestures preserve the memory of the absent church while creating a contemporary, usable place. Three openings connect the ruin to the park: the former main entrance and two passages at the site of the choir. In this way, the ruin has become a permeable enclosure, a place simultaneously defined and open. Its interior is marked by two shallow steps, a blue-stone pavement and a shallow pool, for which the architects refer to the Canopus at Hadrian’s Villa. This delicate intervention gives the ruin a new identity: no longer a mere romantic fragment, but a distinct architectural space that once again takes its place as the heart of the beguinage.

A second focal point in the garden is the new tower, a hexagonal structure in brick, standing 30-metres tall – the height of the original church. Situated at the edge of the site, beside the gatehouse, the tower is accessible by stairs and a lift. From its top, one enjoys stunning views of Hasselt and the surrounding area, including the mining pits of Genk, which are a reminder of the region’s industrial past. The tower re-establishes the beguinage as a vertical marker in the city’s skyline, signalling the presence of the university. Yet it does so not as an act of domination, but as a gentle, friendly gesture – an invitation to the city and its inhabitants.

As one of the few green enclaves within Hasselt’s inner ring, the beguinage today serves both the university and the wider public. A new circular opening in the northern wall increases permeability, connecting the site with the public library and Hasselt University’s Faculty of Law, itself housed in a former prison adapted by noAarchitecten in 2012. The transformation of the beguinage thus forms part of a broader trajectory. Founded in 1971, Hasselt University was originally located on the outskirts of the city, established to aid the regeneration of a region in decline after the collapse of mining. Over recent decades, however, the university has extended its presence into the historic centre, repeatedly through the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. In this respect, the integration of the beguinage as a university faculty is more than a single project: it is a continuation of a deliberate strategy to anchor the university in the urban fabric, while giving new life to buildings of shared memory and value.

Credits

Client

The Province of Limburg

Architect

Bovenbouw Architectuur, David Kohn Architects

Structural engineer

Bollinger+Grohmann, Triconsult

M&E consultant

Arcade Engineering

Heritage consultant

Architecten Beeck & Hermans

Landscape design

Landinzicht Landschapsarchitecten with Ingenieursbureau France

Acoustic consultant

M-gineers

Landscape

Vandersmissen

Bespoke furniture / joinery

Beenens

Steelwork

SmeGo

HVAC

SPIE

Window frames

D’huys

Brick

Wittmunder

Interior doors

Xinnix

Door handles

FSB

Heating

Jaga

Insulating plaster

TCS CALCE

Interior lighting

RZB, BEGA

Interior paint

Rewah

Electricity

Electro Wijnants