Managing partner Simon Bayliss tells Ruth Slavid why HTA Design is a firm believer in modular construction

At present just two per cent of housing is prefabricated. When I ask Simon Bayliss, managing partner at HTA Design, what proportion he thinks it could reach, he says “I would plump for 50 per cent”. And this is Bayliss being cautious. With the exception of some one-off houses, he believes that “everything mass produced or speculative could be modular”. In other words, almost all housing.

Bayliss is certainly an enthusiast for modular housing. So much so that he has written a book on the subject with colleague Rory Bergin. Called ‘The Modular Housing Handbook’ and published by RIBA, it shows a range of fascinating projects by HTA and others, and also sets out the arguments for widespread adoption of the approach.

‘The Modular Housing Handbook’ (RIBA Publishing, 240pp, £40).

Although the book talks about the history of all types of manufactured housing, its main emphasis is on the volumetric approach – the creation of whole rooms that can be delivered on the back of trucks. It puts forward several strong arguments for their use, not least faster construction and improved environmental performance.

Greenwich Millennium Village, designed in 1998, was one of HTA’s first attempts to use Modern Methods of Construction.

Getting to this point has taken Bayliss his entire 22 years in practice. He looks back to the Greenwich Millennium Village where, he says, “We were full of big ideas that the industry couldn’t respond to. It has taken the industry 20 years”. Over that period, HTA has worked with a number of companies but now co-operates closely with Vision Modular Systems on a range of projects, including the newly complete 101 George Street in Croydon.

This comprises two towers, one 38 and the other 44 storeys, consisting exclusively of homes for rent. HTA describes itself, Bayliss says, as “designers in industry” – that is, part of the industrial process, not completely detached designers.

Now that industry is able to do this work properly, there are, he believes, many advantages. One – and it may be counter-intuitive for some – is architectural freedom. “If you take the constraints and benefits and work with them”, Bayliss says, “you get quite a lot of architectural freedom. There is freedom in material specification and in quality of finishes”.

And, he says, by working in this way, the architect has no fear of being kicked off the project part way through. “Nobody would conceive of changing architects”. Instead, the practice is involved from a very early stage, right through to post-occupancy evaluation – and yes, that does happen.

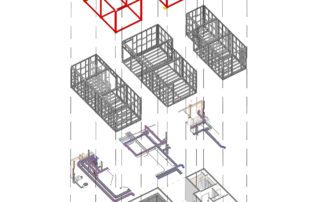

101 George Street completed, under construction and exploded view of its modular apartments. The two towers comprise 1500 modules manufactured in Bedford and delivered to site replete with services, kitchens and bathrooms. Each module at 101 George Street has a unique steel structural design tailored to its position in the building, allowing an efficient frame. It is clad in “jewel-like” glazed terracotta panels.

It is no coincidence that many of the modular projects with which HTA is involved are build-to-rent, since this is where the big advantages are for developers. Modular construction is much faster – the units are made in a factory and then delivered and craned in. The upfront cost is higher, but clients also begin to receive income more rapidly, and this is the main driver when building for rent. It is one of the reasons that hotels were quick to embrace volumetric construction.

For example, HTA completed a student housing project of 550 flats at Wembley, north London, within a year. A similar project built by another practice using conventional construction took two and a half years, missing the rental income for two years.

But there are wider benefits than just to the pockets of developers. Environmentally there are several wins, and some of them are surprising. Despite the fact that the transport of the units themselves is inherently inefficient – trucks are carrying large volumes of air, rather than neatly stacked components – transport impact is actually reduced relative to conventional construction, says Bayliss. “On a building site”, he notes, “you have huge numbers of deliveries coming to and from the site”. Deliveries to the Vision Modular Systems factory near Bedford are, in contrast, well-organised. In addition, 75 per cent of the factory workers cycle to work, whereas construction workers – constantly changing their place of work – are likely to drive or, at best, use public transport.

Designed by HTA, Tillermans is the first block to be delivered within the Greenford Quay masterplan in North Ealing, London, and is designed as a build-to-rent scheme. It contains 379 apartments along with resident amenities including a lounge, dining room, gym, bar and games room. “Energy efficiency and sustainability were high on the agenda throughout the design of the building so it was specifically designed and optimised to be constructed using offsite manufacture which reduces waste and construction traffic while improving quality and speed of build”, says HTA Design. The architect teamed up with Heriot-Watt University during the design stages to analyse the embodied energy of constructing and maintaining the building, “and showed that by using offsite manufacture, more than 26,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide has been saved. Compared to conventional construction, modular construction techniques reduced both construction site traffic and site waste by 80 per cent”.

Modular projects also tend to use less concrete. In total, Bayliss suggests, the reduction in carbon used in construction is around 40 per cent compared to a conventional project. “It has really opened my eyes”, he says. He was quoting research by Heriot-Watt University which looked at a single project (HTA’s Greenford Quay in Ealing, London) and compared the environmental impact using conventional construction and modular construction.

The research looked at 10 environmental indicators, ranging from land use and water footprint to embodied energy and global warming potential. On all 10 of these, the modular solution scored better.

What this research did was to provide hard numbers confirming what many people knew instinctively. One would expect, for instance, that modular buildings would be more airtight because of the better manufacturing processes. Another advantage of factory production, Bayliss says, is that acoustic and fire separation tends to be better. This is because walls between modules are thicker – two walls instead of one. Given how much of a problem noise can be, this is a real benefit.

At the time of its completion in 2017, HTA’s 29-storey Apex House in Wembley, north London, was Europe’s tallest modular building. “Constructed using the Vision Modular Structures modules, the building was begun and completed in a twelve-month period”, says the architect. The modules were made from steel frames and a concrete floor and fully finished internally when delivered. They were connected to each other and to the slip-formed concrete core after being craned into position.

It may also be obvious that accidents are likely to be reduced by moving production from the building site to the factory. In addition, Bayliss says, factory employment – which is less heavy, less exposed and more family-friendly because it does not require mobility – results in a more diverse workforce. At Vision Modular Systems, Bayliss has noticed more young people than on a typical building site, more people approaching the end of their working lives, and a higher proportion of women.

The most visually striking aspect of volumetric housing occurs with high-rise, city-centre projects when one sees the elements lifted in by tower crane, and the whole taking shape incredibly quickly. But HTA also has examples of low-rise housing and suburban homes that one would never suspect to be modular once they are complete.

The design challenges are different. With high-rise there may well be bespoke design because the overall form of the building is not regular. However, this will be balanced out by the number of special units that are made. In contrast, on lower-rise projects, where the total number of units is smaller, it is desirable to make them as standardised as possible.

Urban Splash’s ‘house factory’, its shedkm-designed Town House at Irwell Riverside, and the later Fab House design – by TDO Architecture and George Clarke – at Smith’s Dock in North Shields.

With houses this should be relatively simple, since most are fundamentally alike. Where the picture becomes more interesting is in low-rise apartment buildings.

Bayliss talks approvingly of developer Urban Splash’s approach. In a number of its projects, which have investment from Japanese housebuilder Sekisui House, the underlying design is the same. The homes are designed by shedkm and the developer has now formed Urban Splash Modular and is building out in a number of locations, with units made in a factory acquired from SIG. These are homes for sale, not rent, and the first scheme, in New Islington, Manchester, sold out rapidly.

Bayliss likes these schemes because of the concentrated research that went into the development, and also because the homes are well designed. “There is a danger that you can get caught up and driven by logistics, by the set-up in the factory”, he says. “But these projects should be driven by good design. You do not want, for example, to have open modules that are stitched together on site”.

HTA, Ilke Homes and Sovereign Housing made the winning entry to a Sunday Times competition seeking the terrace of the future. Intended to cost £100k to build, and be built in less than 100 hours on site, the design proposed factory-made modules with a choice of facade and interior details realised through 3D printing, laser cutting and CNC carving.

Another advantage of the Urban Splash schemes in his view is that they are clad in sheet materials. Hand-laying of bricks is a slow process, so brick cladding can work against some of the advantages of modular construction, and applying brick slips in the factory never looks good he suggests.

One concern about modular construction is future flexibility. Older homes have been changed frequently, updated, added to and had many internal elements replaced. Can this be done with modular homes? Yes, says Bayliss – at least as much as with any other modern home. There will be issues with breaching airtight barriers and so on, but that is true for any contemporary construction. Replacing kitchens and bathrooms should not be an issue and, in the last analysis, it may be possible to take a module away and replace it with another.

The expertise that HTA has built up in modular housing is such, Bayliss says, that he is now receiving enquiries from all over the world. Whereas once UK housing designers were playing catch-up, now they are seen as at the forefront. “There have been a lot of conversations, and a lot of visits”, Bayliss says. And once they have read the book, doubtless the number of visitors will increase still further. Let’s hope Bayliss still has the time to keep designing.