John Pardey on how Joseph Paxton’s pioneering Crystal Palace for Great Exhibition of 1851 marked the end of millennia of masonry and timber construction, ushering in a new era of light, span and prefabrication that would redefine architecture in the age of industry.

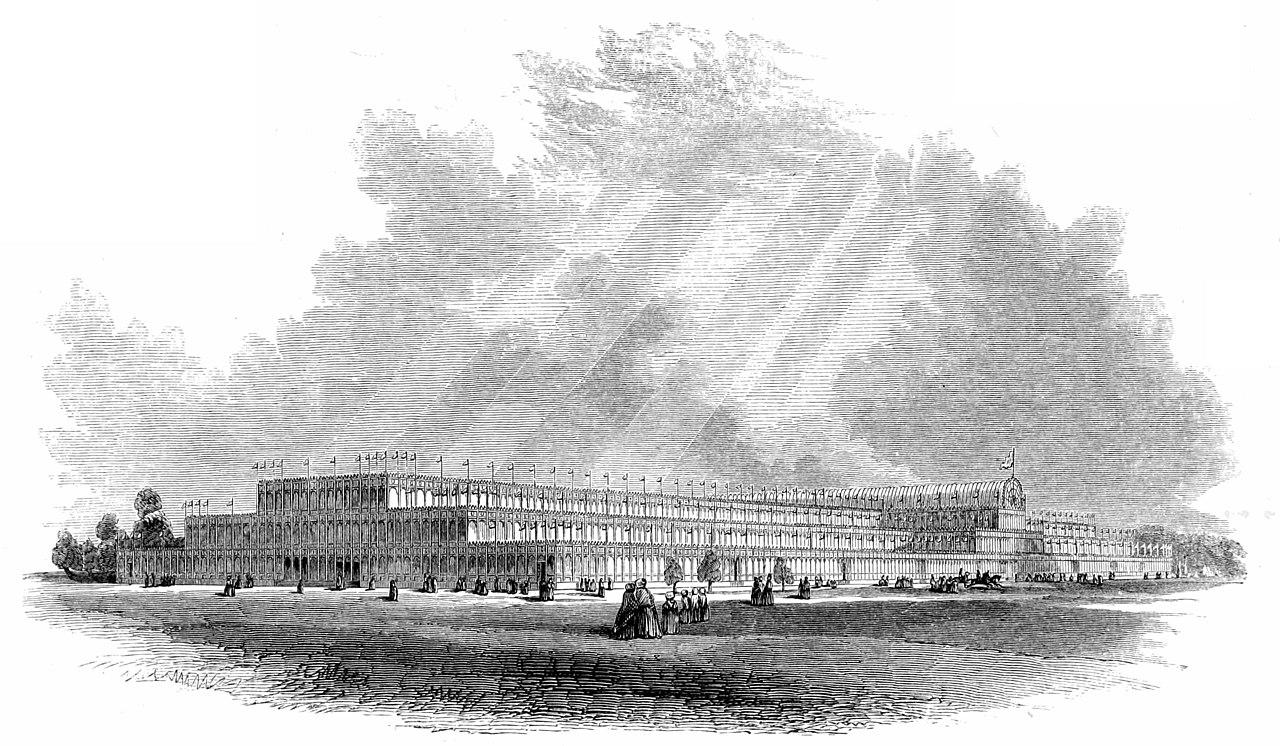

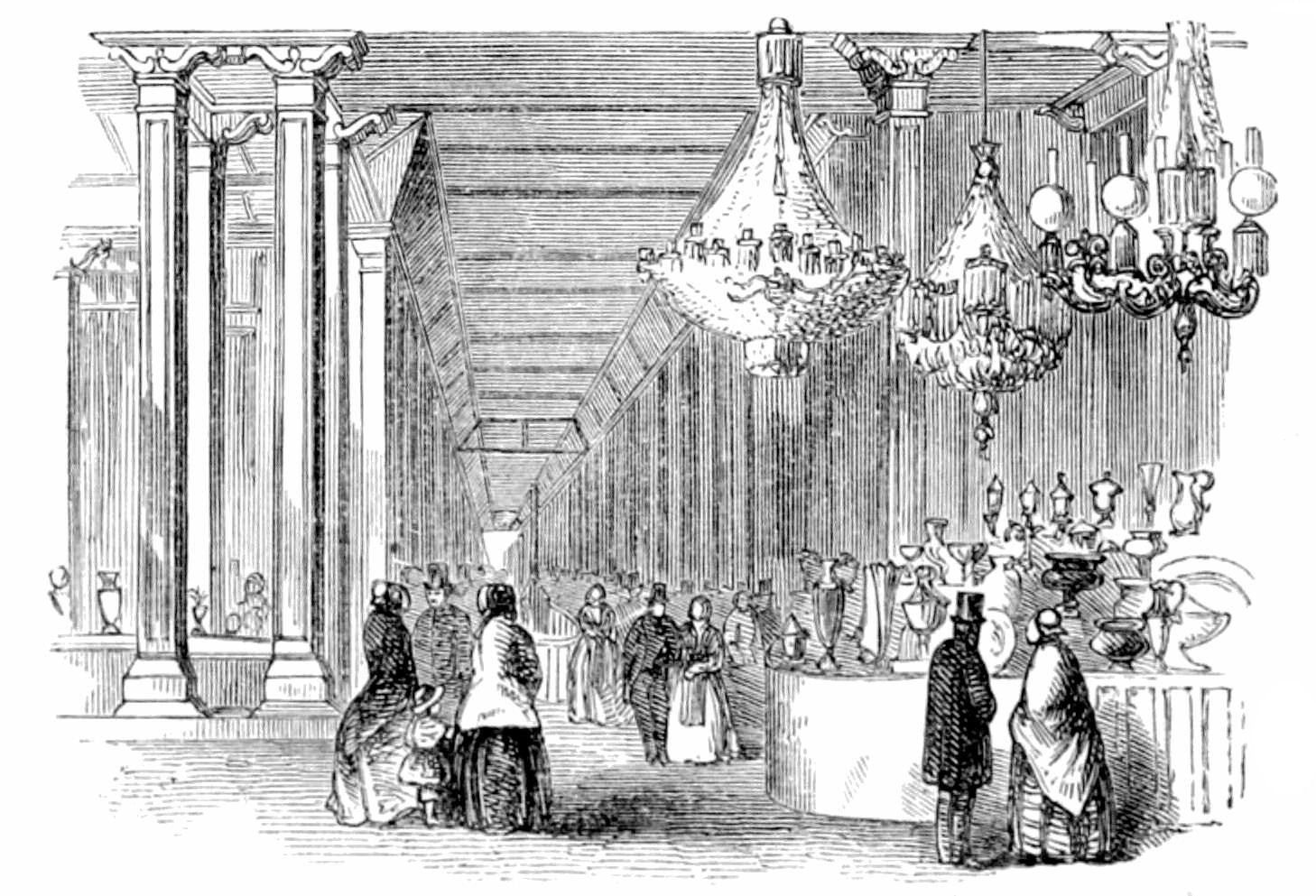

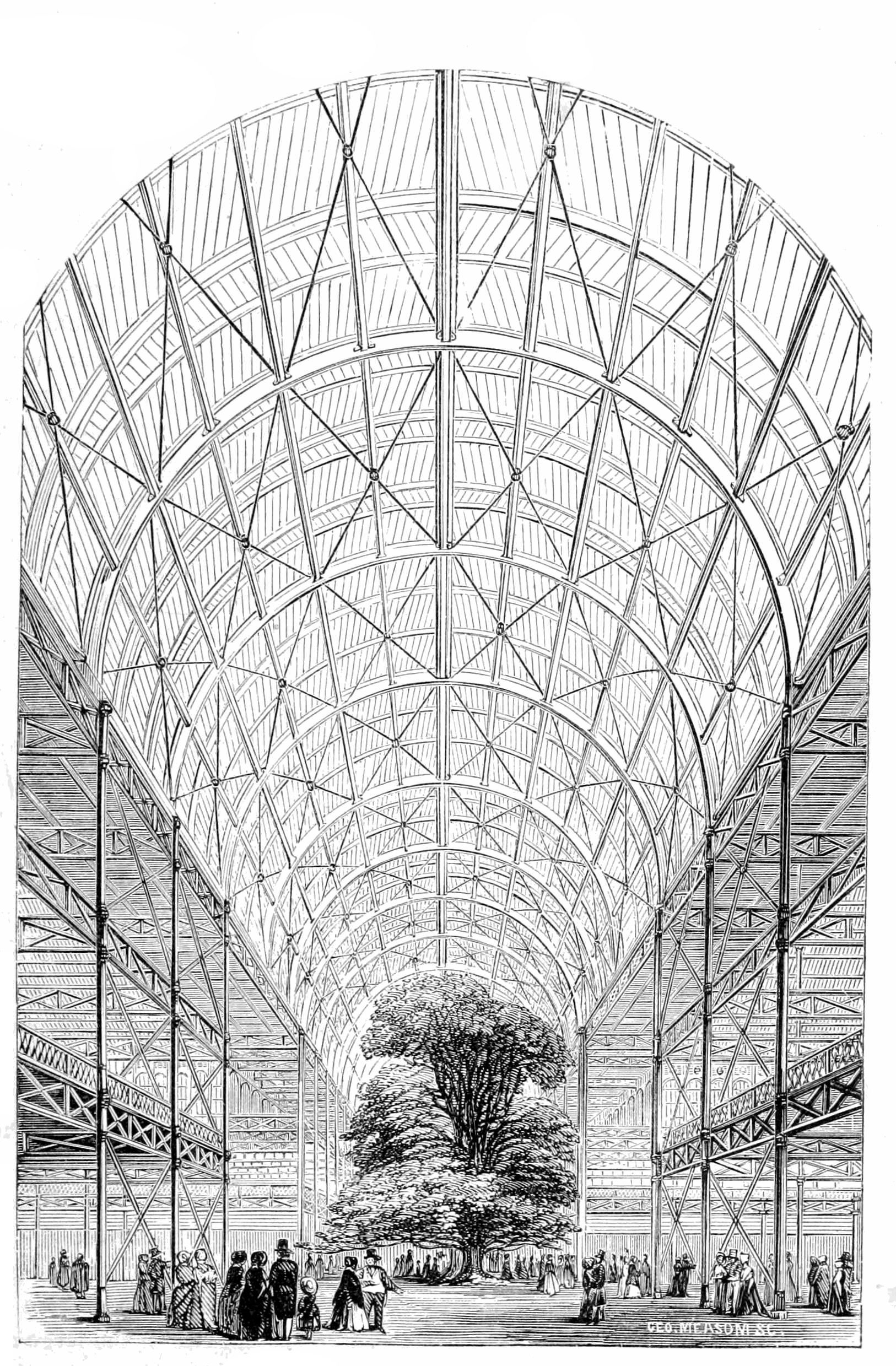

The Crystal Palace in 1851. (Credit: KU Leuven via Wikipedia Commons)

This article is part of a monthly series of short essays on some of the greatest buildings of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Read John Pardey’s introduction to the series here.

No occupation is more worthy of an intelligent and enlightened mind, than the study of nature and natural objects.”

— Joseph Paxton

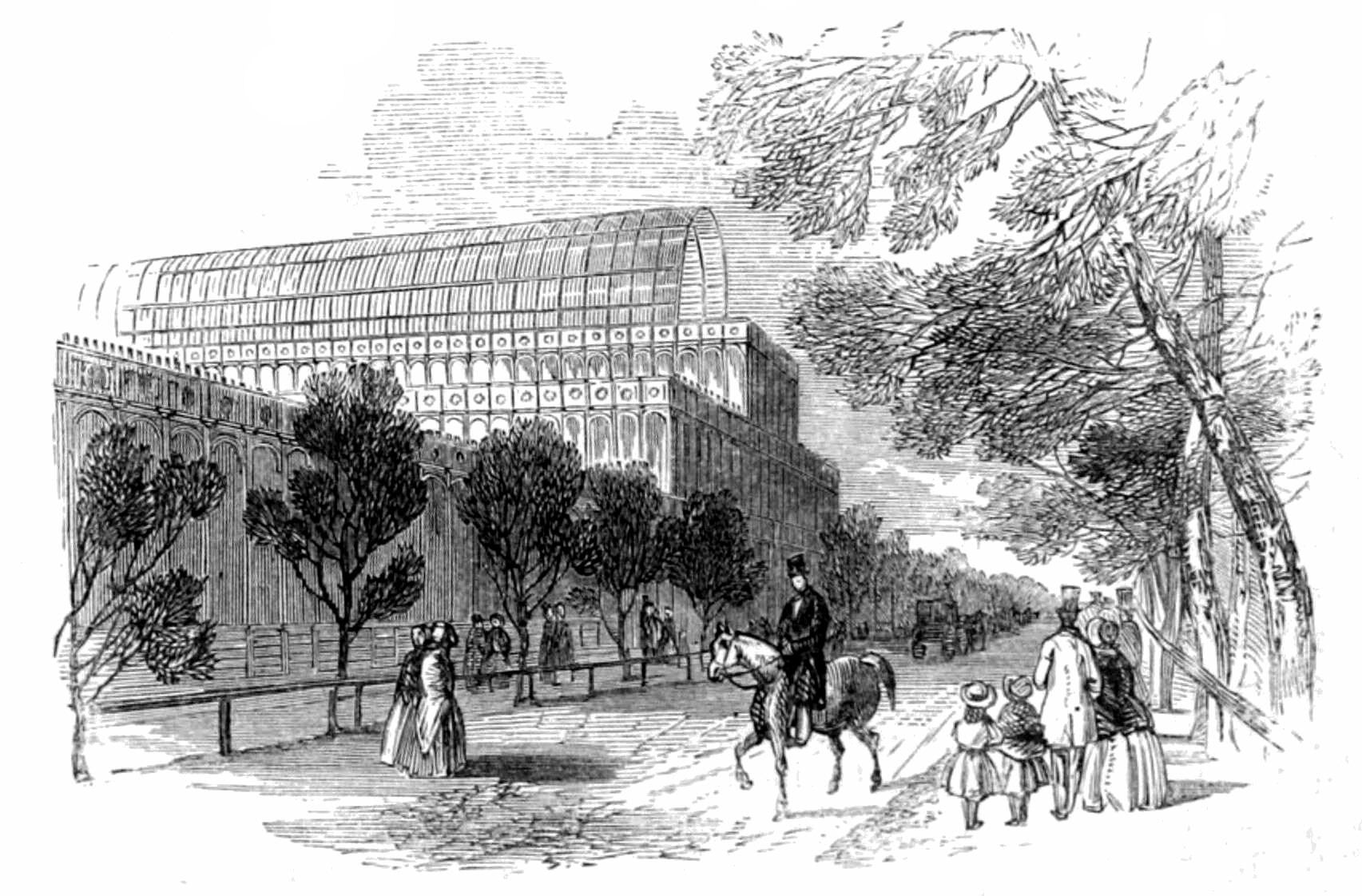

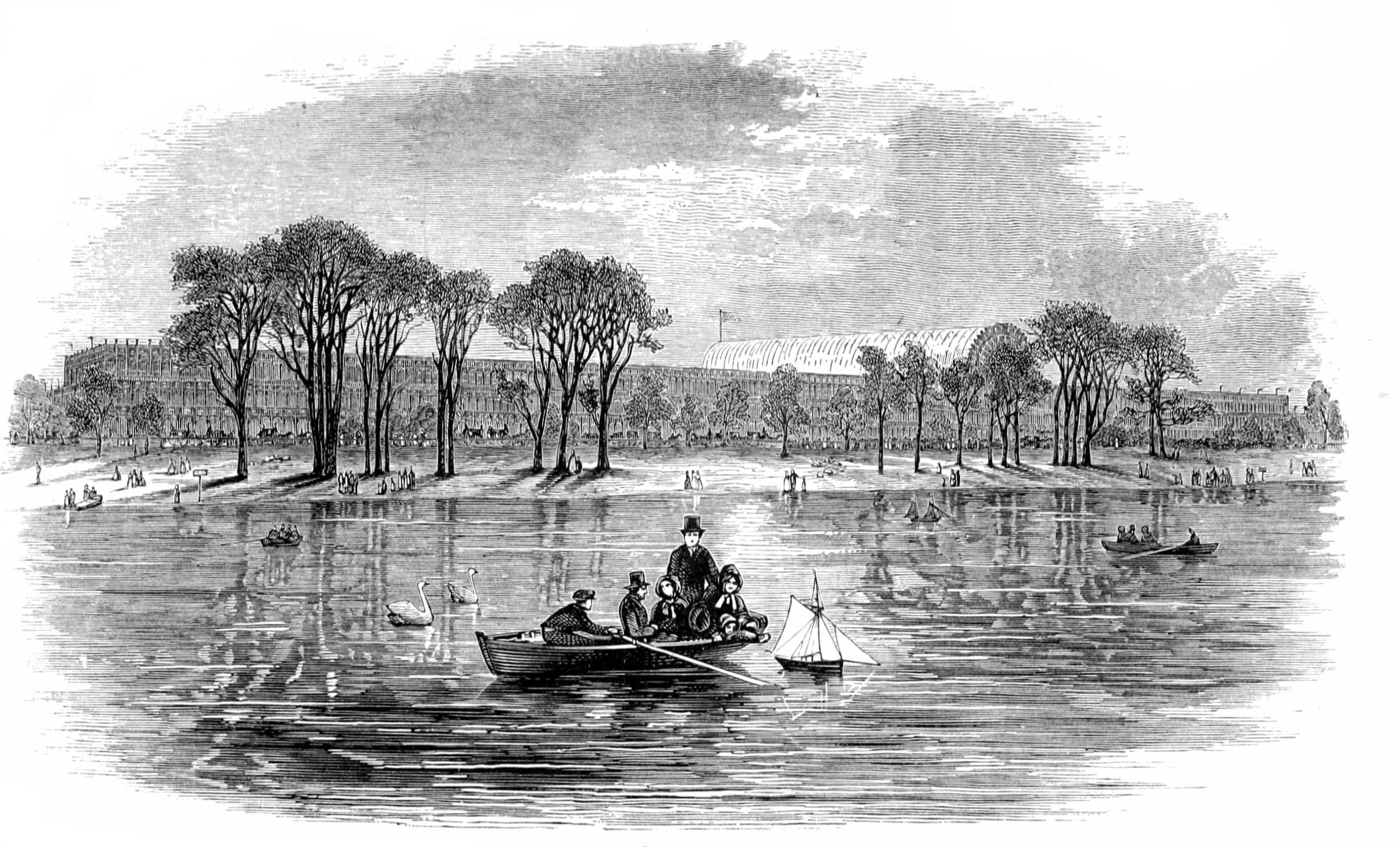

On 1 May 1851, thousands of years of architectural history was ended as Queen Victoria opened the first Great Exhibition in London’s Hyde Park, housed in a spectacular new structure – the Great Exhibition hall – that became known as the Crystal Palace. Up to this point, buildings were masonry or timber constructions, with restricted abilities to span long distances. But in Britain, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, new materials were being developed that enabled a leap into larger-span structures – and combined with large sheets of glass – would generate a new conception of space. Upon its opening, the Great Exhibition hall would dazzle the public with its vast scale and diaphanous carapace, supported by a filigree structure. Nothing had been seen like this before – and it was not created by an architect, rather by a gardener: Joseph Paxton.

The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park for the Grand International Exhibition of 1851. (Credit: Read & Co Engravers & Printers via Wikipedia Commons)

Paxton had been appointed Head Gardener at Chatsworth House in 1826 by the Duke of Devonshire, who clearly saw something special in this young 23-year-old. At Chatsworth, Paxton developed an interest in greenhouses and like many great designers to follow, he was inspired by nature’s structures. His Great Conservatory (1836) measured 69×37 metres in plan and was based on the structure of the water lily leaf – a series of ribs connected to cross ribs – which he translated into columns of cast iron and slender timber frames holding glass panes.

The Great Exhibition committee, tasked with delivering a vast exhibition hall, went out to competition, receiving 245 entries from across Europe. While two schemes stood out – one by Richard Turner (who had designed the Palm House at Kew) and another by a French architect – both of which proposed a cast iron and glass structure, neither satisfied the committee members. Paxton at this point decided to put forward his proposal, which he had sketched out in two days, and submitted detailed plans, calculations and costings in less than two weeks. It proved to be vastly cheaper and quicker to build than any other proposal, and with less than a year to deliver, he got the job.

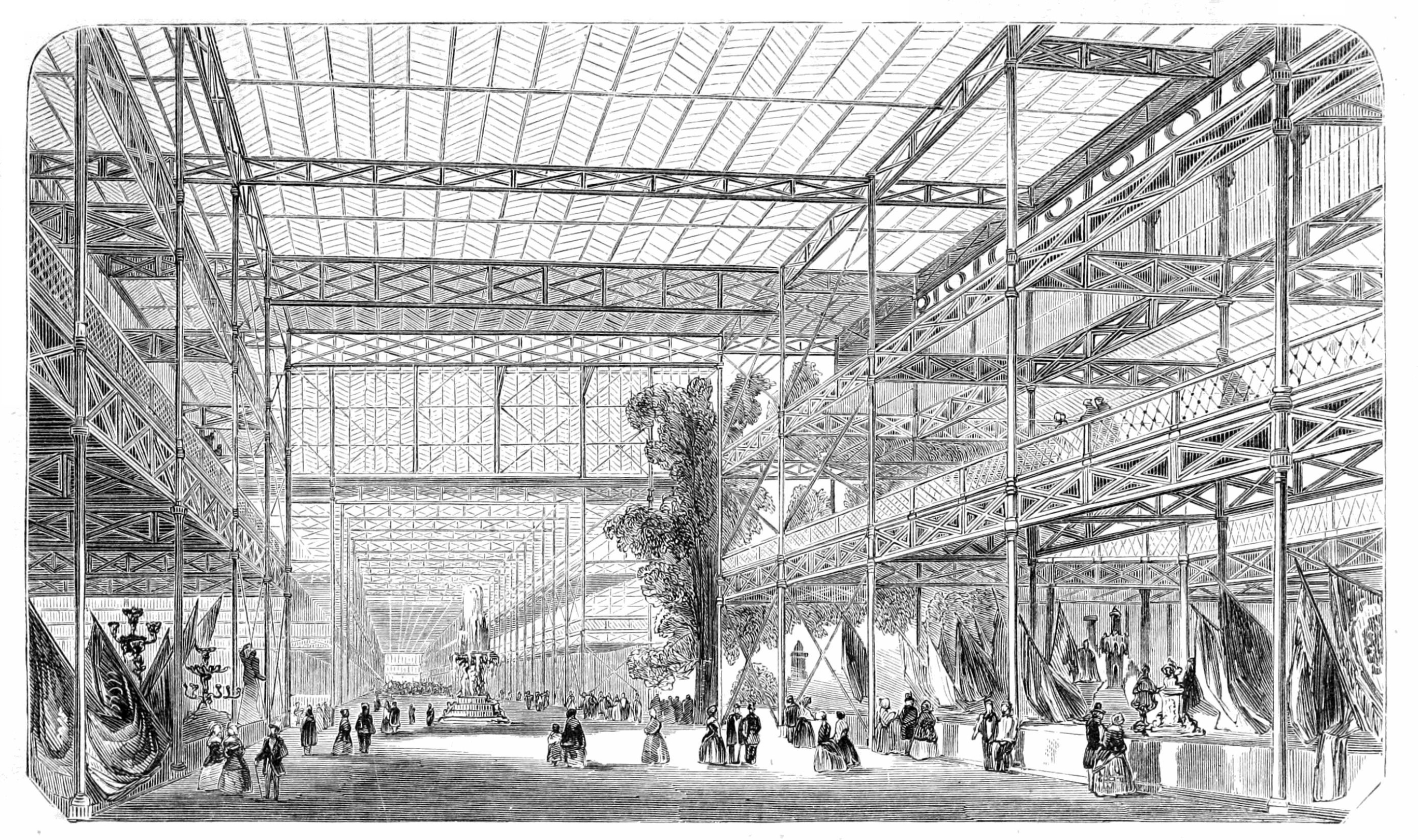

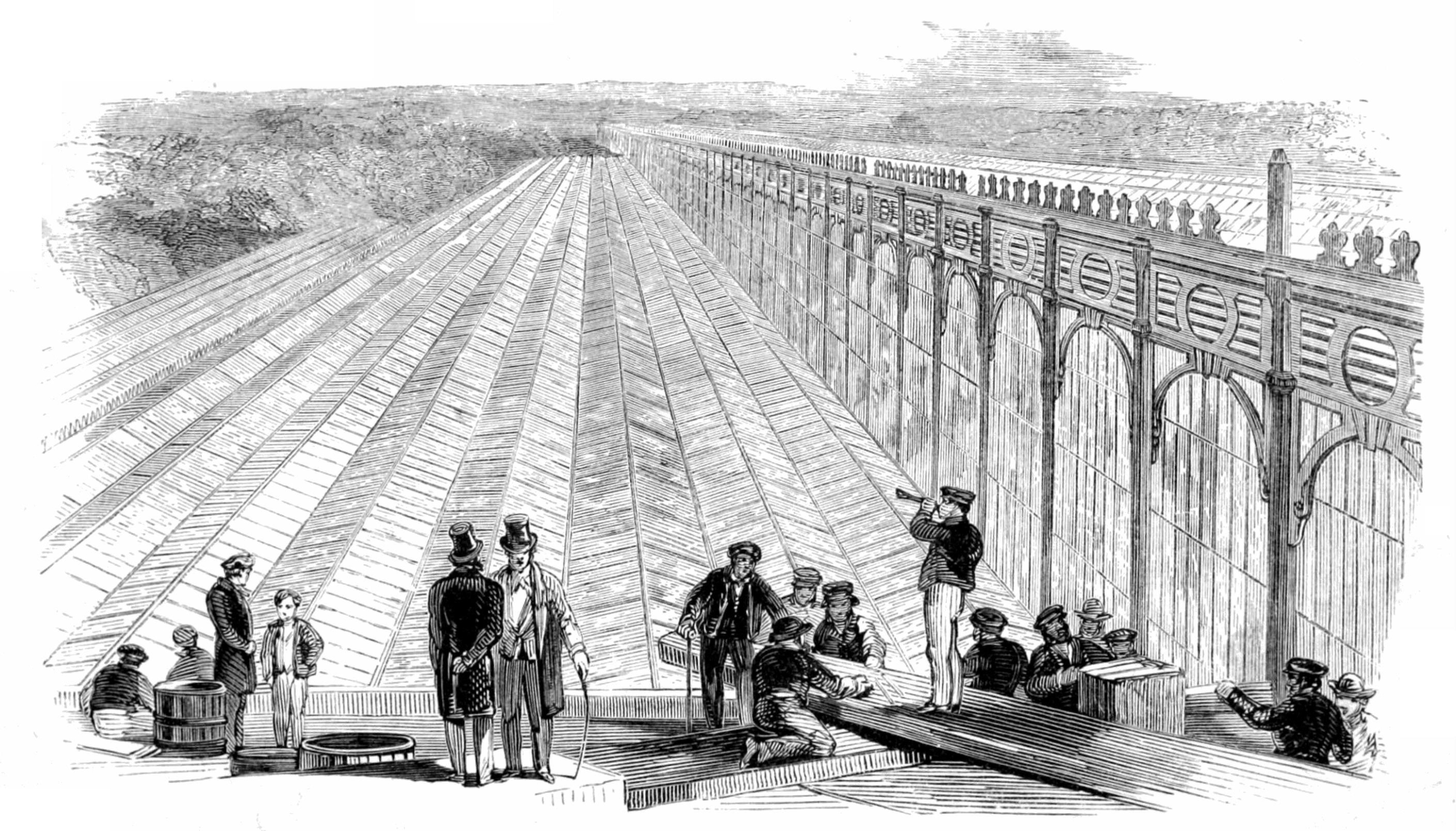

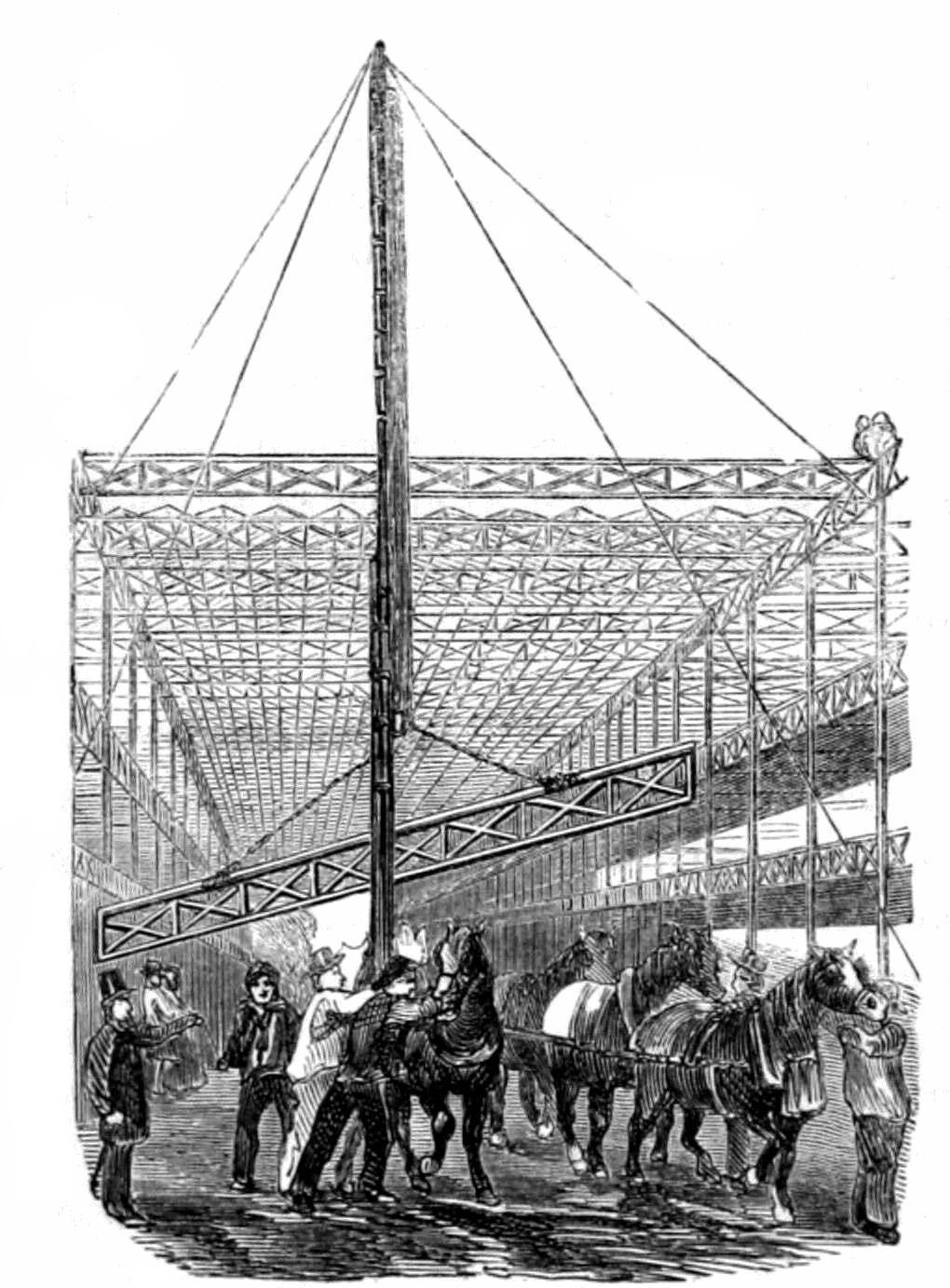

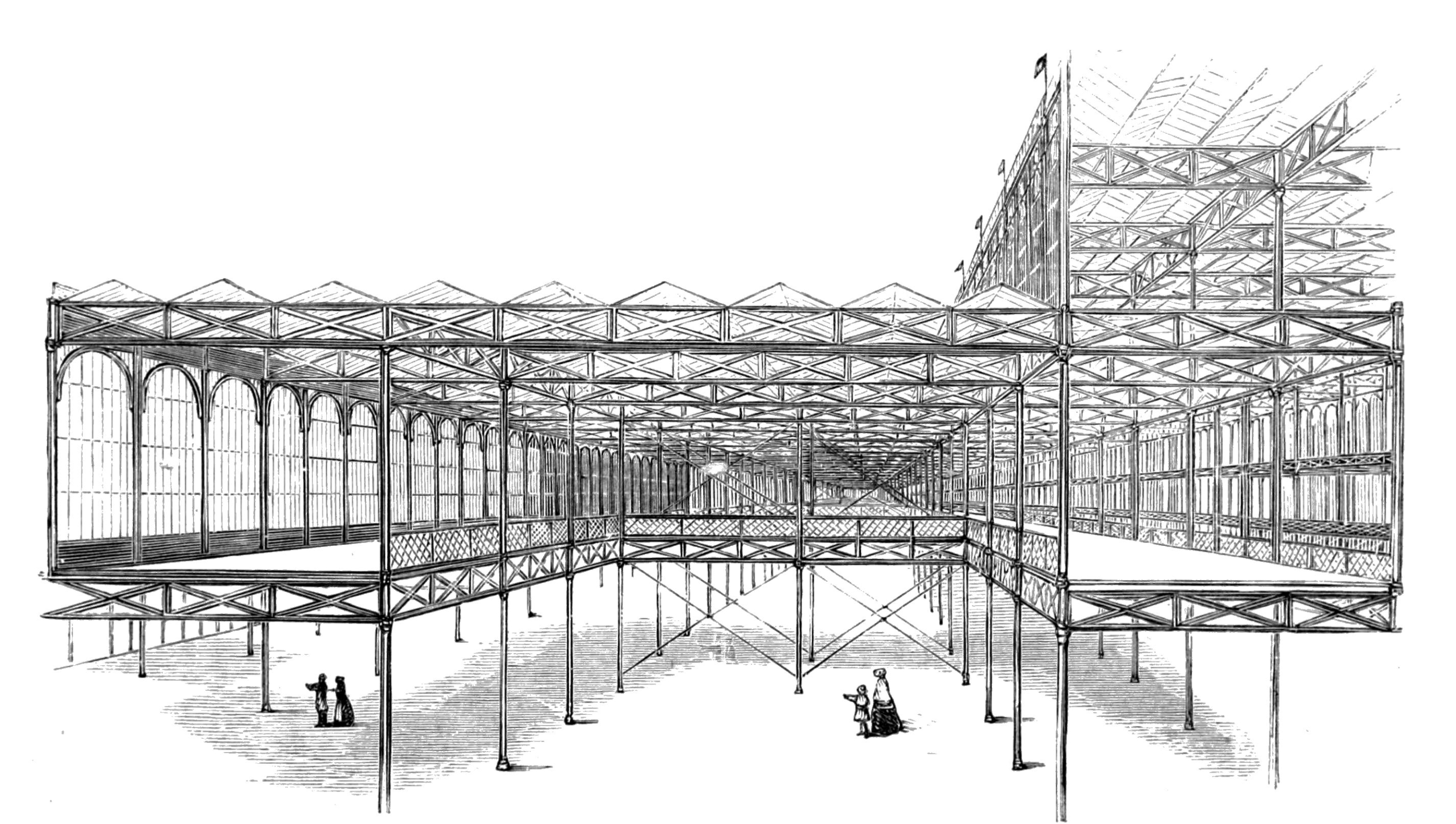

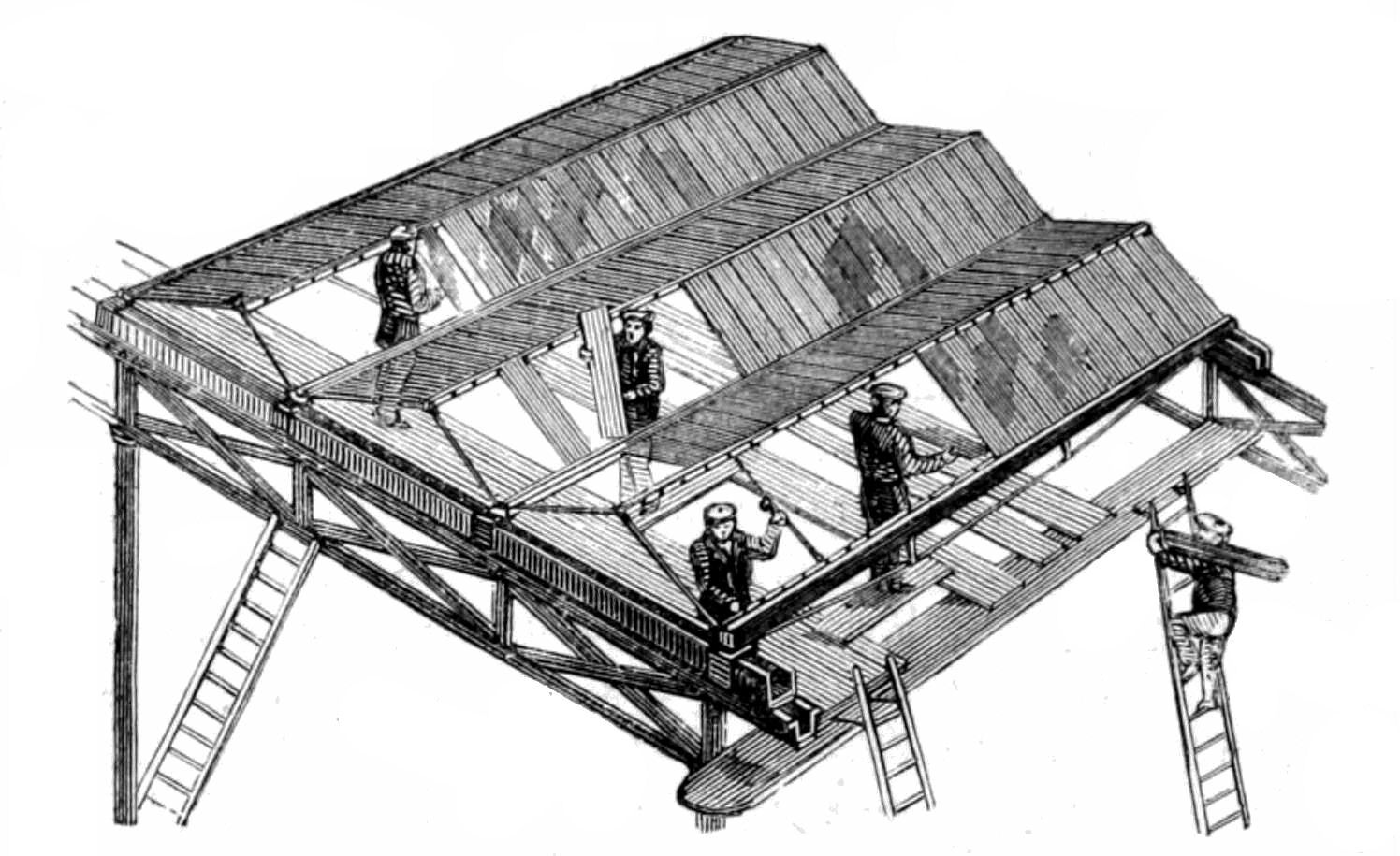

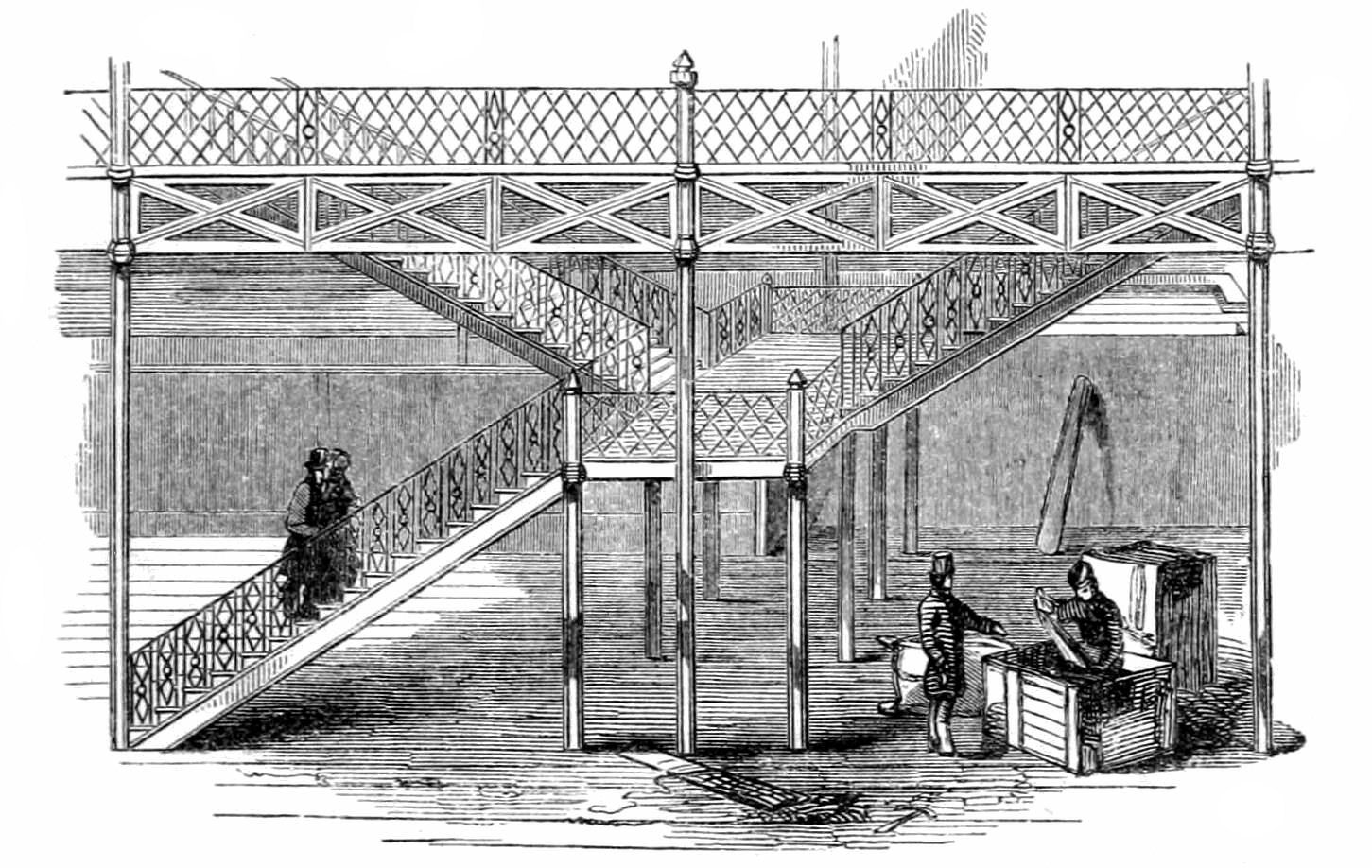

Paxton’s building was to be of an unprecedented scale – some 92,000 square metres in plan (564 metres long by 39 metres high), and large enough to fit St Paul’s Cathedral within it three times over. While the structure was made possible by the use of cast iron columns and slender girders with the largest available size of glass (1320×250 mm), his genius was the adoption of modular construction based on a 7.3-metre grid. As each module was self-supporting and able to be stacked one on top of another, they could be built simultaneously across the site with no cutting of the glass panels. The hall had a barrel-vaulted central transept (enabling the retention of many mature elm trees), while the main roof was a timber spar ridge and furrow system sitting on girders, inspired by nature’s forms.

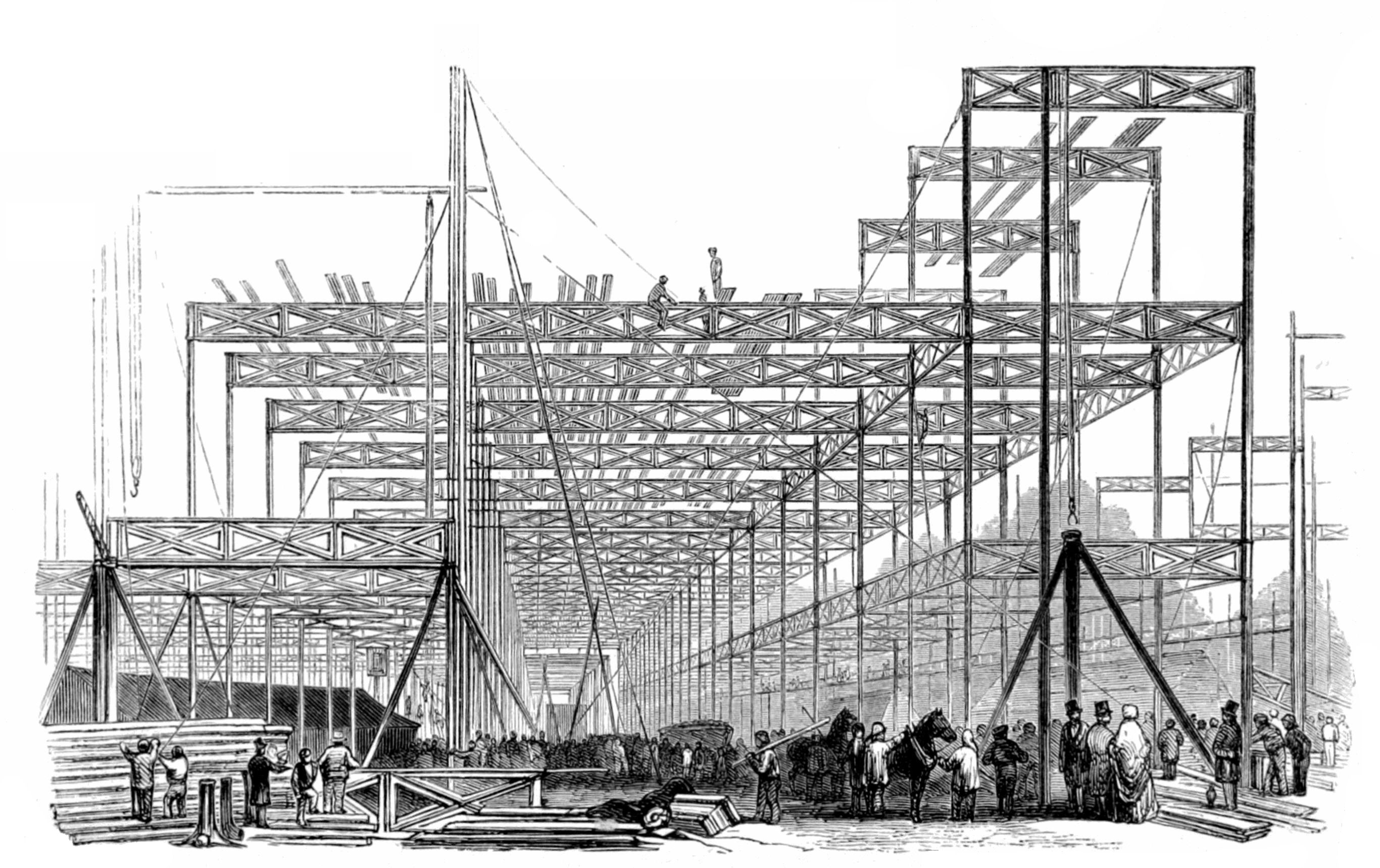

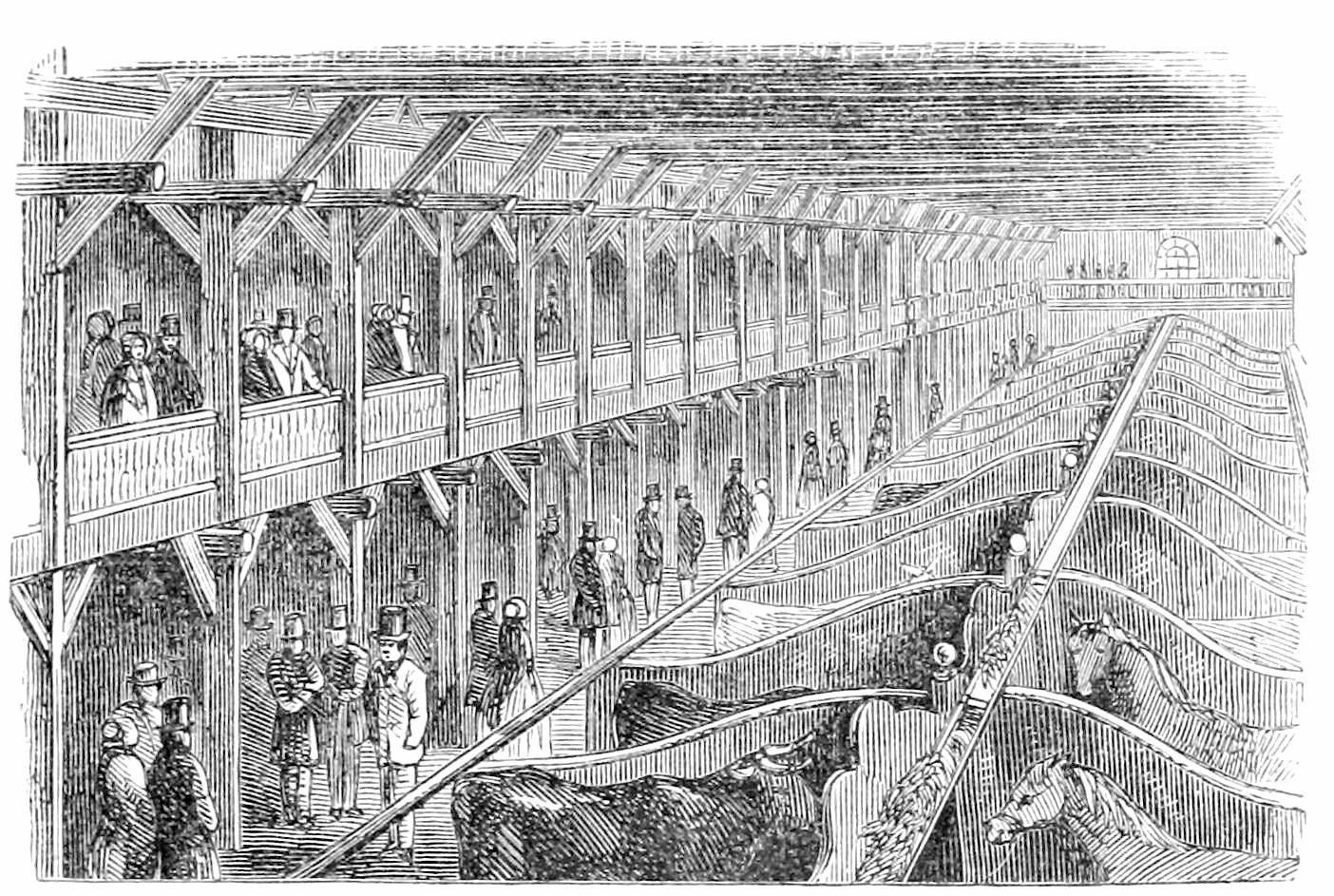

Engravings George Measom showing The Crystal Palace from various viewpoints post- and during construction, including depictions of the 72-feet trusses being hoisted into place. (Credit Peter Berlyn and Charles Fowler Junior via Wikipedia Commons)

The entire edifice consumed some 4,500 tons of cast iron, 5,500 cubic metres of timber and 293,000 identical glass panes. Another innovation that made the rapid construction possible came down to the smallest parts: some 300,000 nuts and bolts. These were the first to adopt Joseph Whitworth’s standardised sizes, that would eventually become a British Standard. It took 2,000 labourers 190 days to build.

The columns were hollow, facilitating rainwater drainage, fed by 48 kilometres of guttering. Overheating during the summer was dealt with by the use of canvas shades draped over the roof and sprayed with water, while arrays of timber louvres in the walls provided natural ventilation for the six million visitors that included Charles Darwin, Charlotte Brontë and Lewis Carroll, who paid to attend the exhibition which displayed 100,000 objects (from the Koh-i-Noor diamond to hydraulic presses) over 16 kilometres with 15,000 contributors. The exhibition made enough surplus income (around £26m in today’s money) to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, Natural History Museum, and Science Museum in South Kensington.

The Crystal Palace was the first modular, industrialised building in the world. It was quickly followed by giant Victorian train station sheds, but its influence on architecture was profound. It showed the potency of new materials to create large span structures, and a new conception of space achieved by a glass envelope held up by a delicate iron structure. It was to be 70 years before the architecture of glass and steel took another leap forward, when Mies van der Rohe proposed a glass skyscraper in 1921 that would become a new typology for the modern metropolis.

The foundation pads for the Crystal Palace still sit below the grass in Hyde Park, a sleeping giant’s footprints that went on to change the world.