John Pardey on how Pierre Chareau and Bernard Bijvoët’s Maison de Verre (House of Glass) redefined domestic architecture in 1930s Paris — fusing craft and industry, transparency and privacy, transforming a bourgeois townhouse into a luminous, steel-framed gesamtkunstwerk.

(Credit: Subrealistsandu via Wikipedia Commons)

This article is part of a monthly series of short essays on some of the greatest buildings of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Read John Pardey’s introduction to the series here.

I have often heard a saying: A house is neither an airplane, nor a ship, or a laboratory – let us rather accept the religion of house-gods than the tyranny of the machine-gods.”

— Pierre Chareau

In 1969 the writer Kenneth Frampton asked whether the Maison de Verre (also known as the Dalsace House) should be understood as a conventional building or rather, as a piece of furniture – not surprising, given it was designed by an interior and furniture designer: Pierre Chareau. What led to this question is how the house is arguably more significant for its interior, and its concerns for the way its habitants occupy space rather than as an edifice in itself.

The clients for the house were Dr Jean Dalsace, a prominent gynaecologist who was to pioneer family planning in France, and Annie, who had been born into a prominent Jewish family that had made money in real estate and was a former English and dance pupil of Dollie, Pierre Chareau’s wife.

(Credit: Subrealistsandu via Wikipedia Commons)

Despite the Dalsace’s wealth, they were members of the French Communist party and patrons of modern art in Paris. Chareau had worked on their apartment interiors in 1923 and five years later when they bought a property nearby, he was appointed to create their new home.

The site was unusual in that it was a five-storey former 18th century hotel that sat at the back of a small cobblestone courtyard off the Rue Saint-Guillaume. Annie imagined a new modern house, but an elderly woman on the top floor refused to move out and, protected by Parisian tenancy laws, the decision was taken to insert a new house into the existing carapace, leaving the top two floors in place.

Following this, Chareau brought his friend Bernard Bijvoët, a Dutch architect, into the project, bringing with him a practical touch to the design.

Walking from a typical 18th century street through a pair of large wooden doors into the modest courtyard, the house is at once astounding for its entire frontage (on two elevations) being a screen of glass blocks. Ever since the Crystal Palace, architecture had become familiar with glass walls: Walter Gropius had pioneered the curtain wall with his Fagus Factory in 1910 and Bruno Taut had built his Glass Pavilion in 1914 at the Cologne Deutscher Werkbund Exhibition. August Perrett, too, had used glass blocks on the stair shaft of his Rue Franklin block as early as 1903, but what appeared here was a vast translucent screen, perhaps more reminiscent of a traditional Japanese house.

(Credit: Subrealistsandu via Wikipedia Commons)

Maison de Verre, however, is not a pavilion structure with four sides and a roof, as only the front and back façades are of glass.

The home is set within a beautifully proportioned frame of slender, black-painted steel, containing panels of 20cm-by-20cm glass blocks, four wide and six high to work with a 91cm module that runs through the entire design creating a façade of 40 bays. Each of the square glass blocks have a circular lens that serve as a counterpoint to the rectilinear nature of the ensemble, and most strikingly mean that at night, the house becomes a giant lantern.

As a result, the glass block façade creates a sense of mystery, a wonder at what lies behind; a veil that tantalises and offers an ethereal experience.

(Credit: Subrealistsandu via Wikipedia Commons)

At ground level, the property’s entrance has been recessed beneath a projecting a black canopy, with storey-height clear glass panels indicating life within. Another five-and-a-half bays of framed glass blocks return to one side with two strips of clear glazed windows to the upper floors, further indicating domestic life within.

The house has a complex plan to accommodate the doctor’s consulting suite as well as private quarters (and a servant’s accommodation) resulting in a series of intricately planned spaces that open and close into themselves. The reception and waiting room are placed centrally, while to the other side lie the doctor’s consulting rooms and a double-height office at the rear onto the garden. The early Modernist obsession with hygiene is evident in the exposed plumbing fittings that reveal a focus on sanitation within the surgery area. Maintaining this visual language, a spindly, tubular steel-framed staircase outside the consulting rooms leads directly to the doctor’s private study above.

The main stair by the entrance separates family life from patients and is enclosed by glass and perforated metal screens with two doors, one curved and the other straight. This beautiful staircase with its broad, rubber-studded treads perching almost invisibly on twin girders recessed beneath appears to float. Ankle-height, tubular balustrade railing hints at security, with no other handrails on offer – Chareau often referring to this beautiful invitation to ascension as his “monumental ladder.”

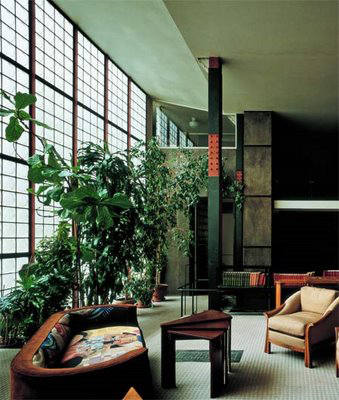

Leaving behind the somewhat disorienting hall of mirrors, the stair arrives in the main salon where light floods the space. Suddenly the house makes sense, revealing a magnificent double-height space with seven riveted-steel supports with joining plates painted in a red-lead orange, the outer flanges being clad in black slate. To one side of the glass block screen a tall array of mechanical, white-painted metal panels are connected by arms and driven by a wheel, like a submarine chamber, providing ventilation to the screen.

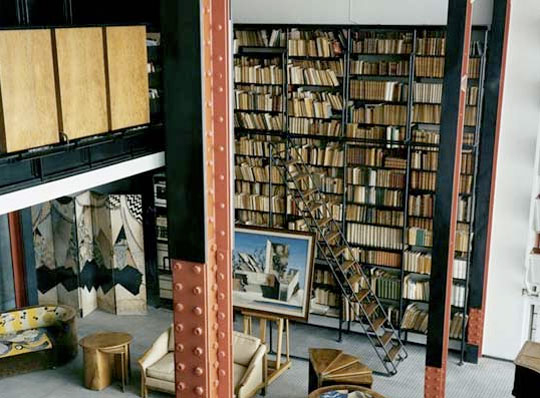

The salon continues the use of the industrial aesthetic with grey-studded flooring and metal-framed bult-in furniture. A bookcase occupys the entire wall opposite the staircase along with bookshelves that double-up as balustrading. The salon’s upper gallery is open but with three-quarter height storage cupboards held on a steel lattice, with metal elements generally being painted black.

(Credit: Subrealistsandu via Wikipedia Commons)

In the private areas of the upper floors, the rubber flooring of the public floor give way to white ceramic floors, perforated aluminium screens and bent Duralumin (used to make sleek doors), while bedroom wardrobes are double-sided to allow maids to tidy up without disturbing the occupants. Moveable screens in bathrooms also provide additional privacy.

In line with the home’s functional vernacular, services are exposed with metal conduits, surface mounted sockets, and finned radiators. The overall effect is that of hand-forged, refined industrial means of production that would have been more familiar with cars and aeroplanes –all of it being crafted by Chareau’s long-term collaborator, the metal worker Louis Dalbet.

The salon was also furnished with Chareau’s own furniture designs which look slightly awkward in his sophisticated industrial interior – upholstered, somewhat art deco sofas and chairs, a small wooden table, a folding screen, a large easel and a grand piano that was used by Annie to entertain guests. The family hosted monthly salon-style meetings attended by Marxist intelligentsia, including prominent artists such as Max Ernest, Jacques Lipschitz, Joan Miro and Pablo Picasso – amassing, in the process, a remarkable collection of Modern Art.

While the house was being built, Annie Dalsace reported seeing Le Corbusier, by then celebrated for his Villa Savoye, several times peeking in across the courtyard. Within a year of the completion of the Maison de Verre, Corbusier built his apartment block in rue Nungesser with its glass-block façade. (The home undoubtedly influenced Le Corbusier and his contemporaries Eileen Gray and Jean Prouvé – as well as, later on, the English Hi-Tech architects of the 1960s).

When the Nazis invaded France, the Dalsace family emptied the house of all their possessions and fled to the Pyrenees to join the Resistance. They were to return after the war when they stayed in the servant’s quarters while the house was restored after four years of neglect. Chareau fled to Marseilles, then Morocco before ending up exiled in New York where he was relatively unknown and endured hardship. He committed suicide in 1950.

Like Rietveld’s Schroder House, another fit for the list of greatest houses from the 20th century, Maison de Verre is a tour de force of detail with almost every element of it lovingly designed and built, created by a furniture designer – and like the Schroder House, involved the direct patronage of highly cultivated women.