AT speaks to artist Madelon Vriesendorp, the first UK-based female recipient of the Soane Medal, about her enduring connection with Sir John Soane, the playful legacy of Flagrant Délit, and why imagination, instinct and curiosity remain at the heart of her work.

How does it feel to be the first UK-based female artist to receive the Soane Medal?<

I’m extremely honoured and delighted that my most treasured museum would give me this totally unexpected recognition.

Why do you think your work continues to resonate so strongly with architects and students today?

I think my work resonates with students today because I have widened the possibilities to approach architecture and its representation from a different angle and view point.

You’ve described your first visit to the Soane Museum as discovering “a kindred spirit.” How do you view the relationship between your work and Sir John Soane’s legacy?

I always have felt a great kinship and affinity with Sir John Soane for collecting and gathering, the compilation and treasure-hunting of objects to tell a complete – or fragments of a greater – story (success or catastrophe), a mysterious history (joyous or grim) that stimulates the imagination and [be] a source of speculation.

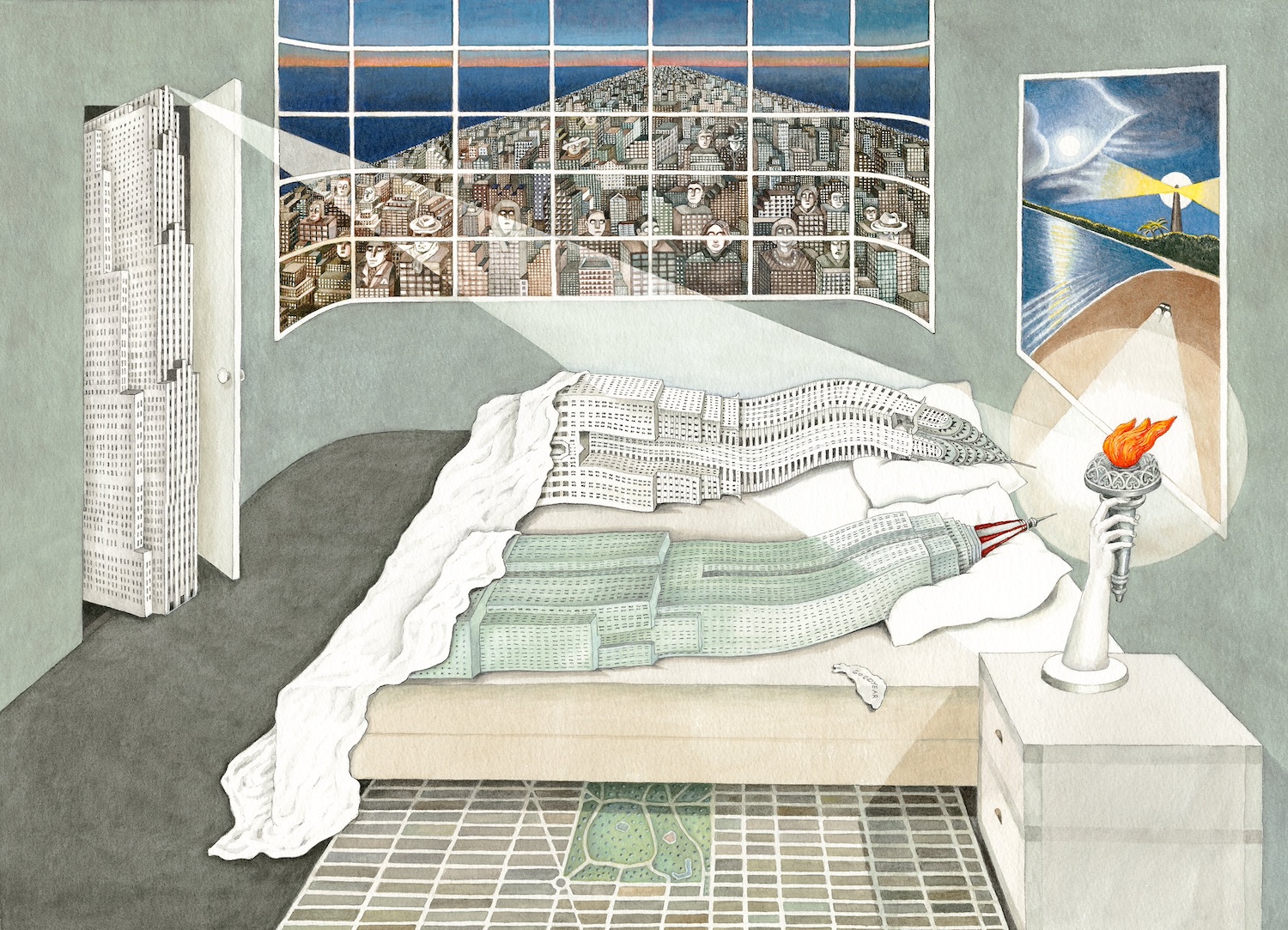

Flagrant Delit. (Courtesy of Madelon Vrisendorp)

How do you see the boundaries between architecture and art – are they fluid, or do you consciously move between them?

I’ve never felt boundaries between architecture and art or the representation of either. As I’ve never been involved in building, architecture has never been more than the visualisation of a concept.

Flagrant Delit has become an iconic image in architectural culture. What inspired that painting, and how do you feel about its enduring legacy?

It has had a surprising legacy as it may have opened up awareness of gender in inanimate objects, in this case buildings. Presenting them in a playful way in a time, the ’60s and ’70s, when sexuality was being explored and struggling against traditions and prejudice.

Did your works visualised theoretical ideas for OMA? How did you translate abstract architectural concepts into these vivid humanised images?

OMA didn’t exist when I painted FD, it was inspired by material we’d collected–books magazines postcards – researching for the book Delirious New York while living in New York City. This material inspired the New York series of gouache and watercolour paintings.

Do you see yourself as an interpreter of architectural ideas or as a provocateur who challenges them?

I never made something thinking that it was going to have any influence on architectural ideas or to provoke them.

Your work often attributes human emotions to buildings. What do you think architecture gains from this kind of anthropomorphism?

I think it’s part of human nature to anthropomorphise everything around us, and the buildings depicted in Flagrant Delit were built at the peak of film stardom, when film studios were anthropomorphising celebrities. Buildings too, dressed up in gold and silver, becoming huge tourist attractions. The Statue of Liberty is a building impersonating a woman or a woman impersonating a building.

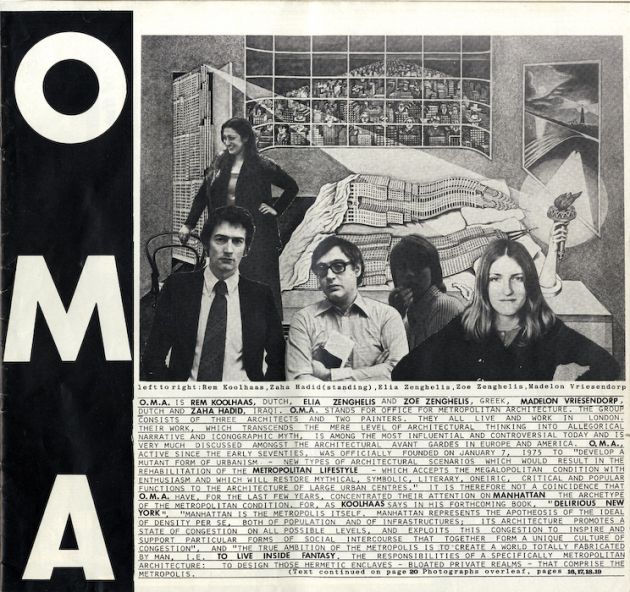

Vriesendorp co-founded OMA with Rem Koolhaas, Elia Zenghelis and Zoe Zenghelis in 1975.

(Courtesy of Madelon Vrisendorp)

What advice would you give to young artists and architects about developing their own visual language?

I would never give young architects or artists advice, only to study the human condition, look around and trust their instinct .