AT chats to… Japanese Pritzker Prize-winning architect, Shigeru Ban about his work in Ukraine, the USA, how he ended up in Paris, and the architects and engineers that inspire him today.

An internal render for the bourbon brand Kentucky Owl’s proposed distillery and visitor centre.

You’re currently working on a cross-laminated timber (CLT) hospital for the city of Lviv in Ukraine. How did that project come about and what will the building achieve?

The Lviv hospital project was started when I made a direct proposal to the mayor of Lviv. It will not only significantly increase the number of surgical rooms, which are currently in short supply, but will also be a hospital built with wood, which is unprecedented in Ukraine, and will be a project that will contribute to the local industry and reduce CO2 emissions by using a large amount of CLT produced in Ukraine, which will heal the inpatients with its warmth.

How did you balance designing a building with many technical demands with one that needed to be able to be built quickly, but well?

The majority of the structural components of this hospital are made from CLT, which is milled by CNC machines in a factory. As wooden buildings, not limited to CLT, are prefabricated, the process of manufacturing the components is not affected by climate conditions, the time required for on-site construction work is short, and as the components are highly precise, there is little need for unnecessary rework, so high-quality buildings can be realised in a short period of time. In addition, timber construction generates less noise, dust and vibration in construction compared to steel or reinforced concrete buildings, so it is also suitable for construction on hospital campuses.

Why did you eschew the need for metal joints?

Using metal joints is the easiest method, and I sometimes use them depending on the circumstance. However, in many cases, I try to avoid using metal joints because I enjoy coming up with different ways to join timber components without depending on metal plates.

What’s the status of the project?

We are in schematic design phase, busy on day-to-day coordination with local architects, engineers and specialists. Many of them are Ukraine local and we enjoy working with them.

Shigeru Ban with Ukrainian representatives in Lviv.

Another project I see on the boards is for the Kentucky Owl bourbon brand. What inspired the pyramid-shaped design of the wooden buildings for the brand’s new distillery-campus?

This distillery is a building that can be seen from all 360 degrees, and it was necessary to contain multiple tall pieces of equipment within it. The ideal way to meet these conditions was with a triple pyramid.

The site is a former quarry. How did this determine the campus layout?

Although it’s not really obvious from the photo, the site has quite a variation in elevation, and the design and layout of the main access, visitor centre, maturation warehouse and bottling centre were naturally decided to make the most of the characteristics of the site.

Above and below: Renderings and drawings showing aspects of the Kentucky Owl distillery and Visitor Centre.

In your book, Shigeru Ban. Complete Works 1985–Today, you mention quite a few architects and engineers as having influenced your practice. Reflecting now, who has influenced you the most and how?

It is absolutely impossible for me to single out one architect who has had the greatest influence on me. I have been influenced by each of my great predecessors in different ways. For example, Mies van der Rohe has influenced me in terms of detail and spatial composition, Alvar Aalto in terms of the use of materials and thoughtful design, and Emilio Ambasz in terms of the fusion of architecture and nature. If I start to list them, there is no end to it.

And the engineers?

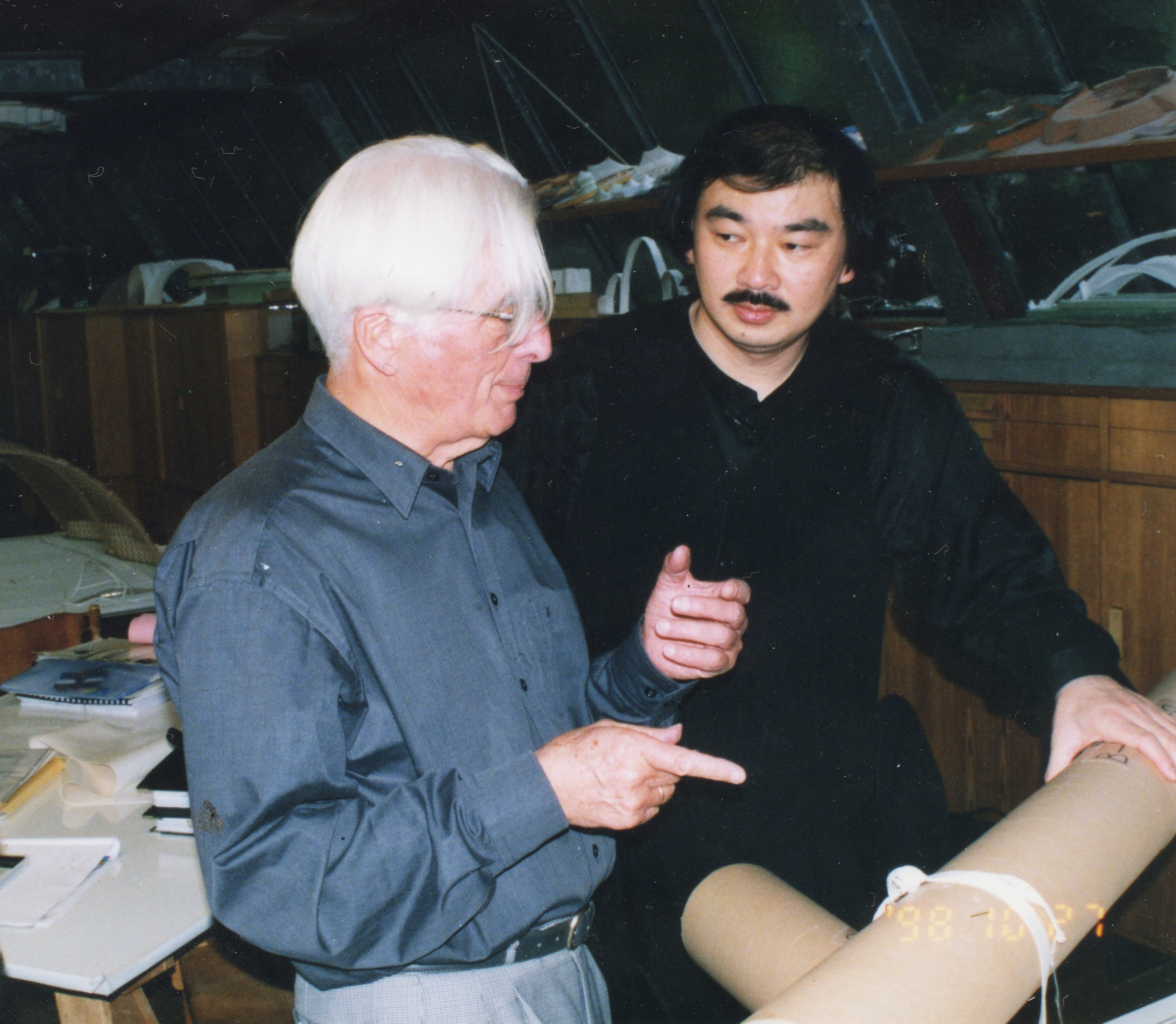

Just like architects, each structural engineer gives me different inspiration. However, Frei Otto is a man who has no boundaries between structural engineer and architect, and his work also is a direct expression of structural system as architecture. As I was not interested in design trends, I greatly sympathised with his approach to develop structural systems. For this reason, when I was appointed to design the Japan Pavilion for the 2000 Hannover Expo with paper tube structure, I approached Fri Otto for his help and we collaborated on the design, and this experience has been of great value in my career.

Frei Otto and Shigeru Ban at the engineer’s studio near Stuttgart, Germany in 1998.

When you moved to Europe, your office was on top of the Pompidou. How did that come about?

I won the competition for the Centre Pompidou-Metz extension for the Paris institution and suggested half-jokingly to Bruno Racine, then President of the Centre, that “the agreed design fee is not sufficient for an architectural firm from a foreign country like us to rent an office in Paris. So if you could lend us space on the terrace, we can build our temporary office.”

It was necessary to get the permission of Renzo Piano for this design and he accepted it quite happily. He told me also that when he and Rogers won the Pompidou Centre project, they created a temporary office on a boat anchored on the banks of the Seine. In this way, my temporary office was connected to the history of the Pompidou Centre. Piano warned me, though, that it is not a good idea to be too close to the client. He was right.

Is that something that still holds true today? Your current European office is a stone’s throw away from the Pompidou; does it help to still have a base in France?

I thought, [however,] that there was after all an advantage to be close to the client. Often, when a foreign architect wins a major project in any country, they are supposed to work in conjunction with a large local firm. There have been problems with this kind of collaboration, since the local architect inevitably sides with the client, especially for budgetary matters or for scheduling, instead of supporting the original architect’s idea.

For them, the client is more important than the foreign architect who happens to be their partner. If design architects visit only occasionally or send their staff, it is very difficult to follow through on a concept to the very end. Clients who do not intervene much in their work spoil Japanese architects. If an architect is famous or has won a competition, the client remains peaceful. We also have very good contractors, so it is easy to build in Japan. Some very famous Japanese architects have discovered after winning a competition that the completed building is entirely different from what they designed. It is because of this problem that I thought it was very important to be near the client.