An AT event, supported by Schüco and hosted by the Royal Irish Academy of Music, explored the challenges and opportunities facing Irish cities, and what can they learn from each other and from best practice abroad.

Architecture Today’s recent one-day event, held in partnership with Schüco and hosted by Dublin’s Royal Irish Academy of Music (RIAM), took a deep dive into the challenges and opportunities facing Irish cities, and what can they learn from each other and from best practice abroad. The event, which was chaired by AT Editor Isabel Allen, comprised presentations by a diverse range of speakers, including architects, engineers, urbanists, and façade consultants, as well as panel discussions and a walking tour along the River Liffey and its environs.

Speakers (left to right): Enda McGrath, Dan Gleeson, Conor Sreenan, David Browne, Colin Mackay, David Jameson, Andrew Clancy, John Tuomey, Louise Cotter, Peter McGovern, Isabel Allen (chair), Tony Reddy, Jonny McKenna, Denise Murray, Ali Grehan, Stephen O’Malley, Shane Hall, Colman Billings, Paul O’Brien, Cian Dowling, and Sean Mahon.

Morning session

After brief introductions from Enda McGrath, Schüco Architectural Project Manager (UK and Ireland), and Isabel Allen, Dan Gleeson, Schüco Sales Director (UK and Ireland) opened the morning session by welcoming delegates and underlining Schüco’s commitment to creating a sustainable built environment through initiatives, such as carbon reduction in materials and façade remediation. He emphasised the importance of collaboration across disciplines and sectors, arguing that innovation in design and technology must drive the development of high-performance, sustainable buildings and urban spaces. Gleeson framed the ambition for the day as threefold: to highlight how partnerships can accelerate change, to recognise the link between good design and quality of life, and to foster a shared commitment to action that ensures every project contributes positively to both the planet and its communities.

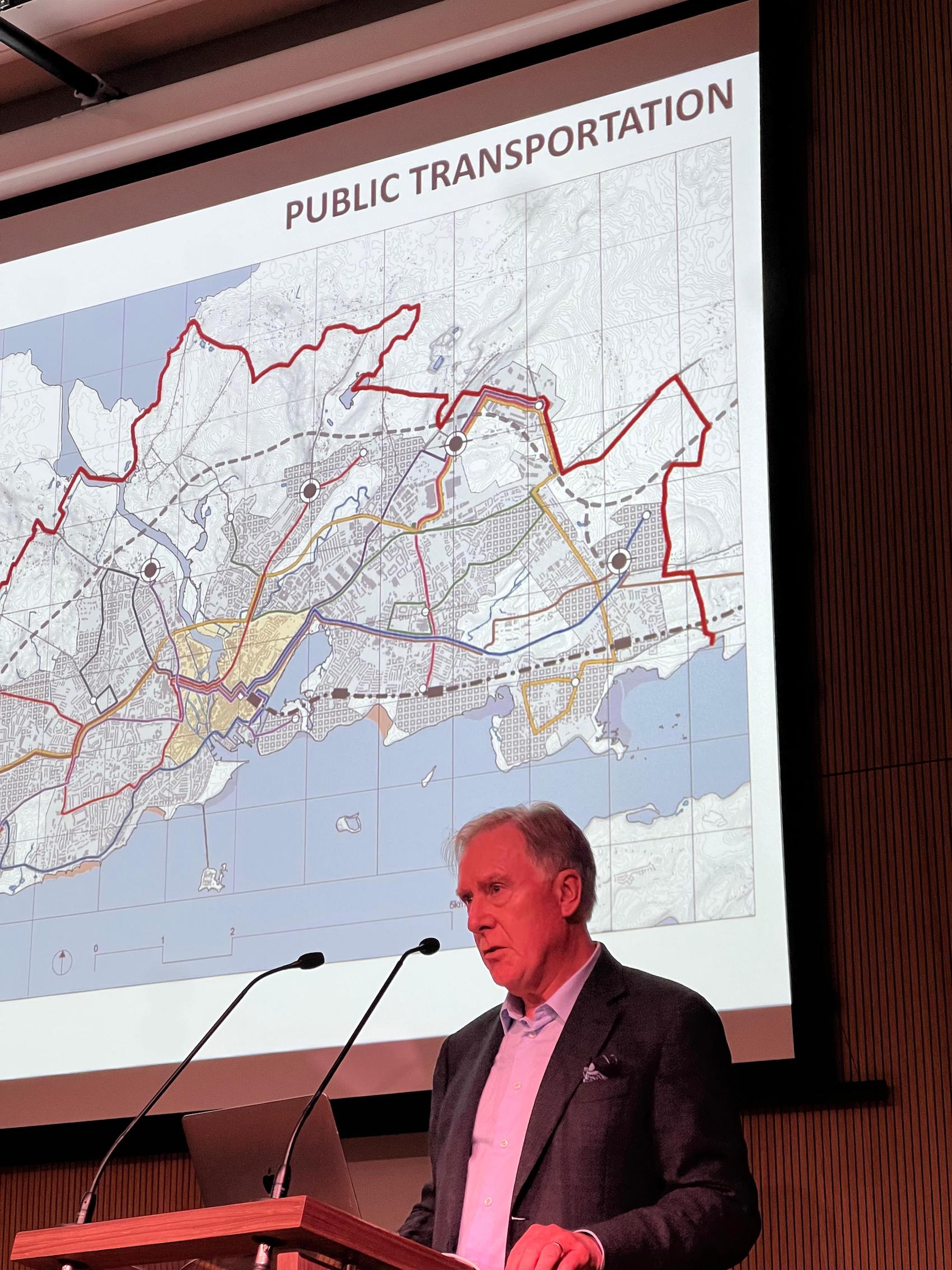

Gleeson handed over to David Browne, Consultant at RKD Architects and former President of the RIAI, who delivered a stark warning in his talk Irish Cities: Opportunity or Crisis. Drawing on the work of the multidisciplinary Irish Cities 2017 group, he argued that Ireland is “at a tipping point” in how it accommodates its rapidly growing population, which is projected to exceed 11 million by 2070. “Land-hungry, low-density urban expansion must stop,” he insisted, criticising field-by-field planning on the peripheries of Irish cities that entrenches car dependency and undermines healthy urban living. National systems of planning and development, he added, are not fit for purpose and are too often stymied by narrow objections to critical infrastructure.

David Browne argued that Ireland is “at a tipping point” in how it accommodates its rapidly growing population.

Using Galway as a case study, Browne contrasted the city’s celebrated centre with its sprawling, congested suburbs, where densities average just 13 dwellings per hectare. “If we continue as we are, we will more than double the surface area of the city,” he warned. Instead, the Irish Cities group proposes accommodating growth within the existing boundary through infill, densification, new park-and-ride hubs, and extensive greenways and tree planting. Neighbourhood studies, such as Renmore, demonstrate how densities could be doubled “without altering the fundamental character of the area,” making public transport viable and communities more resilient. Influenced by European exemplars, such as Freiburg’s Vauban district, the vision has been embraced by Galway City Council and the Chamber of Commerce.

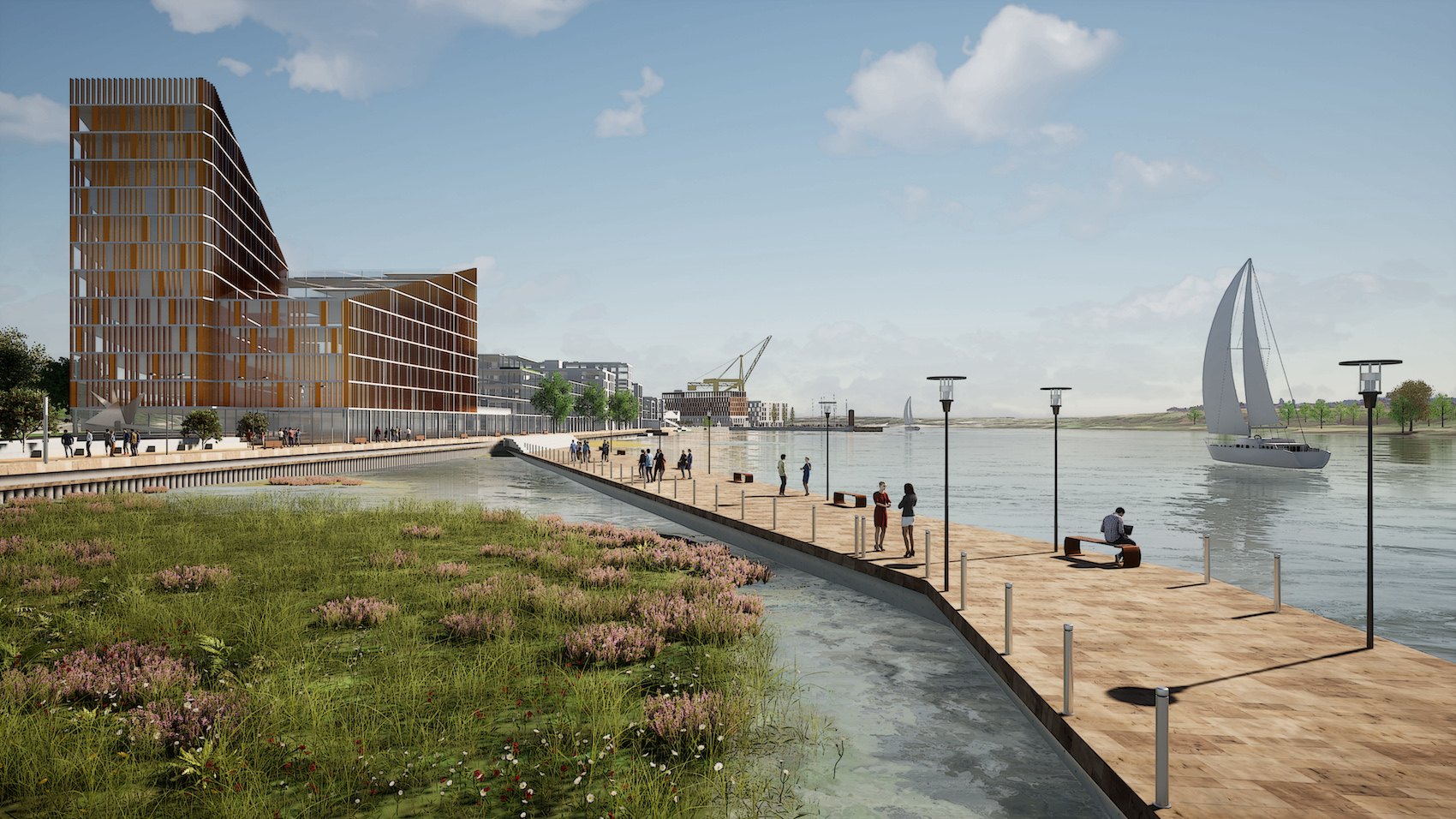

Hawkins\Brown’s Cork Docklands masterplan is intended to transform Ireland’s largest brownfield site (147-hectares) into a world-class, sustainable waterfront neighbourhood, integrating housing, work, and cultural spaces with high-quality public realm and green infrastructure (cgi: Pixelflakes).

Next up, Colin Mackay, Partner at Hawkins\Brown, presented Cork Docklands Masterplan, a 147-hectare regeneration scheme described as Ireland’s largest single urban project. The framework represents a decisive shift from outward sprawl to inward-focused growth, with capacity for 10,000 homes, 25,000 jobs, three schools, cultural and community facilities, and an extensive public realm. Mackay noted that the project is designed to deliver enabling infrastructure rather than prescribe building form. Key investments include a €1bn package of light rail, BusConnects corridors, three new bridges, and flood resilience measures, all intended to “facilitate development, not drive development in itself.”

Mackay emphasised Cork’s rich maritime and industrial heritage, and the importance of flood defences, biodiversity, and public access to the River Lee in shaping the plan. A blue-green corridor will tie together transport, ecology and active travel, while a network of new parks will connect Docklands to the wider city. To achieve climate targets and viable public transport, residential development will need to be delivered at 200–250 homes per hectare with sharply reduced parking ratios. The strategy, he explained, is about creating the conditions for growth through infrastructure, resilience and civic amenity, while leaving design freedom within defined character areas. “It really is providing that catalyst for development that we hoped it would,” concluded Mackay.

Designed by Tún Architecture, Harcourt Terrace Primary School in Dublin was the winning entry in the RIAI/Department of Education competition for a new model urban primary school in 2015 (photo: Ste Murray).

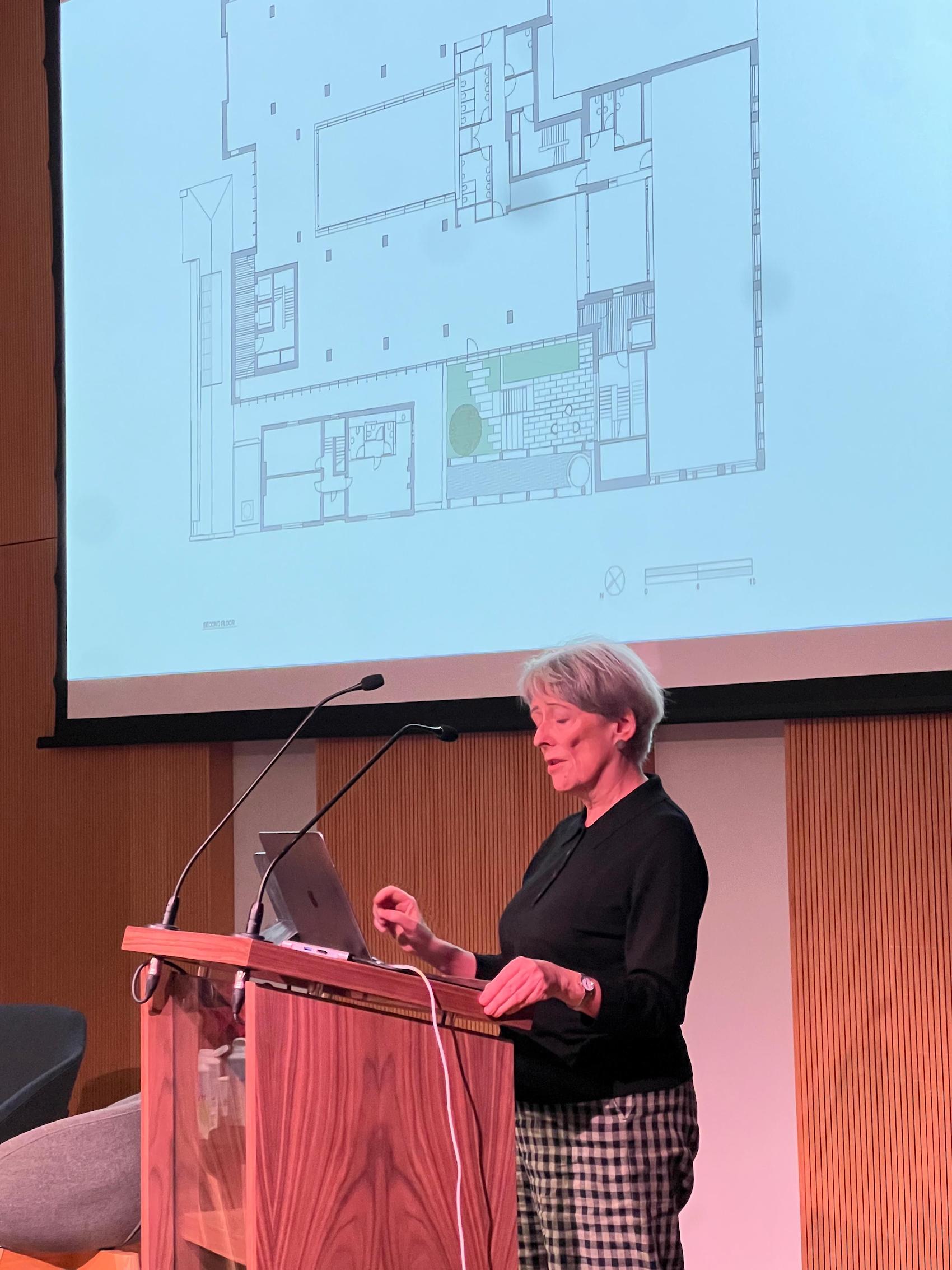

Shifting scale, David Jameson, Co-founder and Director of Tún Architecture, presented Harcourt Terrace Primary School – the winning entry in a 2015 Department of Education and RIAI competition to design new urban schools for 21st-century Ireland. Located on a constrained Dublin site, the 26-classroom school sought to transform limitations into opportunities. Central to the design is the ‘Active Corridor’ – a reimagining of sterile circulation space as an informal learning environment. By treating groups of three classrooms and their shared corridor as a single fire compartment, the design team unlocked 20 per cent more usable space. Toilets and wet areas were relocated to these shared zones, encouraging independence for pupils and freeing classroom layouts for greater flexibility.

The school provides a series of new informal and social learning spaces within the Department of Education’s standard brief (photo: Ste Murray).

The project balances innovation with sensitivity to its urban context. The four-storey classroom block steps down towards neighbouring terraces, while rooftop play areas offer expansive views over the city – inverting the convention of such amenities being reserved for private developments. A robust material palette distinguishes public spaces like the entrance hall, library and sports hall, which Jameson described as “a microcosm of the city.” Light wells and an outdoor amphitheatre ensure even basement areas feel bright and connected to the landscape. Heritage was also integrated: stone from the former Garda station on the site was salvaged and repurposed into external seating and planters. For Jameson, the school demonstrates how tight urban sites can deliver generous and flexible learning environments, where children and teachers alike benefit from new forms of shared space, connections to nature, and a strong sense of place within the city.

Clancy Moore Architects’ innovative and highly accomplished wastewater treatment plant at Arklow, County Wicklow, has dramatically improved the local ecology, amenity areas, and the economic prospects of the town (photo: Camilla Crafa, Piera Bedin).

Staying with key infrastructure, Andrew Clancy, Founding Director of Clancy Moore Architects, framed the practice’s Arklow Wastewater Treatment Plant around the idea of ‘capacity’ – of towns, disciplines, and nations. Ireland’s fast-rising population, he asserted, demands architectural thinking that can “solve ill-formed problems.” Arklow, long capped at around 13,500 people – due to its limited sewage disposal capacity – became a test case.

The team challenged a conventional, horizontal plant by exploiting an 18-metre deep well; stacking processes vertically so gravity drives flows, and in the process freeing more than a third of the three-hectare site for rewilding and public realm. The section-led layout brings sewage to inlet works, on by gravity to biological reactors, and then to a one-kilometre sea outfall, with sludge centrifuged to fuel CHP. Contaminated ground from a former armaments factory was left largely unexcavated – tanks sit on grade – reducing cost and risk, while turning process into legible built form. “Architecture is a conversation,” said Clancy, explaining a listen-first collaboration with engineers, planners and a sceptical community.

In order to minimise energy and carbon, the plant collects sewage 12-metres below the site, before pumping it up 25-metres vertically to allow the entire process to operate under gravity. Electrical energy is provided a rooftop PV solar farm (photo: Johan Dehlin).

The envelope is designed to make the project civic: a gantry-served roof carries photovoltaics to offset pumping, while a perforated green ‘veil’ provides bat niches, and masks internal change –avoiding the need for repeat planning applications. With a 125-year design life and 21 disciplines involved, Clancy positioned the project as proof that firms “of any scale can engage with intelligence and deliver something of lasting value,” and as a call for deeper collaboration to unlock the country’s collective capacity.

Conor Sreenan explored how Ireland can create conditions for change by repositioning architecture as a matter of public concern (photo: Jason Sayer).

Stepping from hard infrastructure to the machinery of state, Conor Sreenan, State Architect and Principal Architect, Office of Public Works (OPW), reframed the discussion around “creating conditions for change.” He set out how architecture sits within Ireland’s constitutional landscape, and why progress depends on making it “a matter of general public concern.” Anchoring his remarks in the 2022 National Policy on Architecture, he highlighted its four objectives – sustainability, quality, leadership and culture – and 45 actions, noting his remit to chair a delivery board. Rather than rush that step, he’s been testing practical levers: formal design-review engagement with Queen’s University Belfast; an internal OPW ‘radio’ to host cross-disciplinary conversations; international exchanges; and a public lecture series with the National Library. A procurement pilot is underway to shift incentives – an “always-on” Dynamic Purchasing System, a follow-on framework, and moves toward removing turnover and fee as selection filters – to help “reposition the value of the discipline within government priorities.”

That value debate will be taken public during Ireland’s EU presidency via a conference titled ‘Value for Many’. This is intended to bring non-architects to the table, including civil servants, diplomats, disability advocates and city leaders, alongside practitioners. Sreenan’s wider aim is cultural as much as technical: to understand “the value systems of others” who steward public funds and use public goods, and to communicate with a general audience before designs are fixed. Fittingly, he closed with drawings – early, explanatory studies for the Dublin’s General Post Office (GPO) and the north-east inner city – intended to precede proposals and “create conditions for change” by making the character and provenance of places legible to citizens.

Currently under construction, O’Donnell + Tuomey’s, Academic Hub and Library at Technological University Dublin’s Grangegorman Campus is conceived as a landmark building and showcase for learning, research and academic activities (cgi: ZOA3D).

Following a short coffee break, John Tuomey, Founding Director of O’Donnell + Tuomey Architects, presented two civic projects currently under construction: the Academic Hub at TU Dublin’s Grangegorman campus, and the Culture House for Fingal County Council in Swords. Both are, in his words, “libraries in all but name.” At Grangegorman, the academic hub sits at the centre of a masterplan that transforms a former walled asylum into an open campus. Conceived as the ‘town hall’ of the university, it will bring together social and study spaces around the refurbished North House, with new limestone-clad wings framing courts and gardens. Tuomey emphasised how the design works within the masterplan’s tight ‘red-line’ footprint, carving solidity and permanence into forms that respect the Victorian building, while opening long windows south to the Dublin Mountains. The building has been designed to grow in increments, with unfinished edges deliberately left ready for future expansion.

Due to complete in 2026, Culture House Swords by O’Donnell + Tuomey is a new public library, theatre and gallery for Fingal County Council in Swords town centre. The project includes a new civic space, designed to complement the historic castle setting at the end of Main Street (cgi: Picture Plane).

At Swords, the practice is developing a Culture House beside the 12th-century castle. Here, the strategy began not with the building itself but with the urban context: asking why the surrounding parkland did not continue all the way around the castle? That shift in mindset, now widely embraced, allows the new building to form an edge to a civic space linking park, castle, and county hall. At its heart is a ‘living room’—an open, public gathering space leading up to library platforms overlooking both the castle walls and town. Cast concrete interiors and a precast stone exterior reinforce the triangular geometry of a tight site, while triangular voids bring daylight through the stacked floors. For Tuomey, the common thread between both projects lies in creating civic rooms that feel open and invitational. Libraries and cultural buildings, he explained, are some of the last truly free public spaces, where thresholds are blurred and entry is unquestioned.

Louise Cotter explored two decades of Cotter & Naessens Architects’ site-specific work in Newtown Pery, Limerick (photo: Jason Sayer).

Louise Cotter, Founding Director of Cotter & Naessens Architects, reflected on two decades of work within Limerick’s Newtown Pery, where an 18th-century Georgian grid provides both the structure and the constraints for contemporary development. Continuing John Tuomey’s theme of thresholds and civic rooms, she described how small, incremental projects – often negotiated plot by plot with shifting owners and planners – allowed for a fine-grained mix of uses and a continuously active ground floor. Early phases included the River Building on Henry Street, combining bar, workplaces and apartments, as well as a series of distinctive infill projects, such as a narrow glass-fronted block shielded by stainless-steel blinds. Each intervention sought to repair and extend the urban fabric while respecting the rigour of the original grid.

Cotter & Naessens Architects has led the transformation of the historic Hanging Gardens site in Limerick, once home to William Roche’s 19th-century stone vaults and terraced gardens. The Gardens International project unites restored vaults and former post office buildings with a new office development, creating a mosaic of old and new at the heart of Newtown Pery (photo: Paul Tierney).

Her presentation culminated in Gardens International (in collaboration with Denis Byrne Architects), a pilot project for Limerick 2030 that reimagines the long-derelict ‘Hanging Gardens’ site. Echoing Conor Sreenan’s call to reposition architecture’s value within public priorities, the scheme stitches surviving stone vaults and GPO fragments into a new concrete-frame office block, a brick-framed corner building, and a central hall lined in marble that acts as a civic room at street level. Roof gardens, courtyards and lightwells restore the legacy of the terraced gardens, while ensuring light and ventilation for modern offices. Cotter framed the practice’s approach as one of respecting streets and creating generous public rooms – working with fragments of the past to form coherent new assemblies, while acknowledging that urban evolution is a collage shaped by fluctuating economies and enduring civic needs.

Following Louise Cotter’s reflections on working with fragments of the past in Limerick, Peter McGovern, Director at Henry J Lyons, turned to the transformation of a historic Dublin institution: the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI). He focused on the recently completed School of Population Health at 118 St Stephen’s Green, tracing the story back to 26 York Street (2018), where a failed basement development became the foundation for a compact 11,000-square-metre building combining sports hall, auditorium, library, surgical training suites and study spaces. Designed for an institution with a global reach and highly specialised needs, the building rejects generic flexibility in favour of precisely tuned teaching, simulation and collaborative environments. McGovern described how circulation, furniture and material choices sought to support student ‘buddy systems’ and informal study, with a bright ceramic-dotted façade giving the school a distinctive civic identity on the Green.

The Royal College of Surgeons’ new education, research and public engagement building at 118 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin, designed by Henry J Lyons. The ‘folded’ facade creates a dynamic new front entrance and public face for the organisation (ph: Donal Murphy).

The new School of Population Health continues this transformation of the RCSI’s historic estate, weaving teaching, labs, and public engagement spaces into a constrained site framed by protected structures and the Unitarian Church. A serrated façade folds back to reveal the church spire, while a diagonal atrium aligns with its north-facing window, bringing light deep into the plan. The building stacks labs above faculty and teaching spaces, threaded by a stair that climbs diagonally to the top floor and opens views to the Green. McGovern emphasised that the project is about vitality and connection: creating collision spaces for students and researchers, establishing a new front door to the campus, and reinforcing the RCSI’s ambition to attract world-class talent, while remaining embedded in the fabric of the city.

Morning panel discussion

The morning session concluded with a panel discussion chaired by Isabel Allen, and featuring Conor Sreenan, John Tuomey, David Browne and Andrew Clancy. Questions touched on themes of value, public space, city growth, and the role of the architect as an agent of change. Sreenan contrasted UK approaches to measuring social value with Ireland’s more fundamental challenge of convincing government of architecture’s worth. Tuomey emphasised the civic duty of architecture, advocating porous boundaries and buildings that “give back” to public life. Browne pointed to the potential for compact, sustainable growth in Irish cities, drawing on European precedents, while Clancy argued that architecture should be understood as a conversation shaped by uncertainty rather than false certainties.

From left to right: David Browne, Conor Sreenan, John Tuomey, Andrew Clancy, and Isabel Allen (photo: Jason Sayer).

In closing reflections, the panellists were asked what had surprised them. Browne highlighted the richness of cross-disciplinary collaboration; Sreenan stressed the need to communicate architecture’s potential to both government and the wider public; Tuomey called for a rethinking of housing as building communities, rather than simply producing units; and Clancy welcomed the appetite for open conversation, noting the positive role of public projects, competitions and state leadership over the past decade.

Afternoon session

Opening the afternoon session, Tony Reddy, Founder of Reddy Architecture + Urbanism, and former President of the RIAI, contended that Ireland’s discretionary, case-by-case planning system is outdated, inefficient, and unfit for purpose. Rooted in the British model, it has fostered suburban sprawl and stalled delivery of housing and mixed-use communities, leaving the country unable to meet demand. By contrast, he pointed to European cities, such as Copenhagen, Helsinki and Freiburg, where integrated urban design frameworks set clear parameters decades in advance, and are delivered to strict timetables, with planners focused on urban design and landscape rather than development control.

Reddy Architecture + Urbanism’s Tivoli Docks masterplan, Port of Cork, covers 62 hectares and is aiming at creating a vibrant city quarter for 11,000 residents and 4,000 workers. It includes a continuous public waterfront, river vistas, and a central staggered boulevard to maximise connectivity, street frontage and views (cgi: Reddy Architecture + Urbanism).

Following Reddy’s call for a European-style planning system capable of delivering whole neighbourhoods rather than piecemeal housing, Jonny McKenna and Denise Murray, both Partners at Metropolitan Workshop, explored how affordable homes can form the foundation of sustainable communities. They noted that while environmental sustainability is now well regulated, social and economic dimensions are often neglected, with too much emphasis placed on simply delivering units rather than neighbourhoods. The practice’s Oakfield Village in Swindon, commissioned by Nationwide Building Society, sought to reverse that pattern. Through early and meaningful community engagement, the project secured full planning support and delivered 239 homes – organised around streets, squares and gardens – designed for legibility, safety and intergenerational living.

Denise Murray and Jonny McKenna’s presentation focused on how affordable homes can form the foundation of sustainable communities.

The architects stressed that Oakfield was made possible by a visionary client, but argued that the lessons apply more broadly. Sustainable communities require careful urban design, provision of services and social infrastructure, and systems of quality control to ensure built schemes live up to design intentions. They warned against reducing affordability to standardisation alone, pointing instead to design review panels and procurement reforms as ways of maintaining architectural quality. Projects like Oakfield, they concluded, show how affordable housing can provide not just homes, but thriving, inclusive communities – an approach they hope to replicate in Ireland.

Ali Grehan, former Dublin City Architect and current Chair of the Irish Green Building Council, drew on her experience in Dublin and the Cloughjordan Ecovillage to explore how Irish cities might grow sustainably. Using seeds as a metaphor for diversity, resilience and place-specific identity, she highlighted how Cloughjordan, though only partially built, already demonstrates the social intensity and services of a thriving urban neighbourhood.

Ali Grehan asserted that sustainable growth depends less on models than on governance, design as a method of action, and collaborative planning built on trust and clear priorities (photo: Jason Sayer).

Grehan emphasised that while models for sustainable cities are well established – from compact and circular to net zero and green – the real challenge lies in governance and delivery. She called for stronger leadership, potentially through a directly elected mayor, to bring together fragmented responsibilities; for design to be recognised as both a problem-solving tool and a method of action; and for citizen engagement to evolve into genuine collaborative planning built on trust, openness and parity of esteem. Ultimately, she argued, achieving sustainability requires clarity about priorities – choosing what to nurture and what to set aside – if Ireland’s towns and cities are to thrive.

Commissioned by Dublin City Council, the College Green Dame Street public realm project reimagines the corridor between Trinity College and City Hall as a dynamic, inviting public space for all. Working with Scott Tallon Walker and OKRA, Team Civic’s designs centre around nature-based solutions to assist with greening, biodiversity and sustainability (image: OKRA)

Stephen O’Malley, Founding Director and Chief Executive of CIVIC, spoke from an engineer’s perspective about delivering sustainable neighbourhoods. Emphasising the need to combine technical excellence with emotional intelligence, he argued for design approaches that respect topography, landscape and community rather than resorting to large-scale re-engineering. O’Malley described the “urban circuitry” of cities as akin to an electronic motherboard, where the success of neighbourhoods depends on the harmony of interconnected systems. He illustrated this through recent work in Dublin, including College Green, where soft landscapes and water-sensitive design are being used to transform a traffic junction into a resilient, people-centred public space.

Reflecting on longer-term experience, O’Malley highlighted the regeneration of the Cardroom Estate in East Manchester. The 12-hectare site was once one of the city’s most deprived areas, but has, over two decades, been transformed into a thriving mixed community of 2,000 homes, social infrastructure and workplaces. He stressed that the success of such projects depends on time, continuity, and a balance of social and environmental factors, with residents retained and integrated into the renewal process. For O’Malley, sustainable neighbourhoods are built not through one-off interventions but through patient investment, collaborative design, and a systemic approach that allows communities to flourish.

Intended to be one of Ireland’s most sustainable buildings, the redevelopment of A&L Goodbody’s HQ at 25 North Wall Quay, Dublin 1, was designed by Henry J Lyons, in association with façade consultant Arup Facades (BDA for client), specialist façade contractor Alucraft, and façade systems manufacturer Schüco (photo: IPUT Real Estate Dublin /A&L Goodbody).

In the final presentation, Colman Billings, Managing Director at Billings Design Associates; Shane Hall, Technical Director at Alucraft; Paul O’Brien, Director at Henry J Lyons; and Cian Dowling, Director at Axiseng, framed the delivery of sustainable growth in Dublin through a series of contemporary projects – several of which were visited as part of the subsequent walking tour. Billings argued that the city must be more ambitious on height to achieve meaningful density, while also acknowledging the urban-realm challenges this creates. All four speakers stressed the importance of collaboration between façade consultants, specialist contractors, engineers and architects from the outset, with energy and daylight modelling now central to design decisions that reduce demand on building services.

Designed by Henry J Lyons, the Treasury Annex Building is located in Grand Canal Street, Dublin. The project features Schüco glazing systems, which were designed and installed by specialist façade contractor Alucraft (photo: HJL).

Case studies illustrated both the opportunities and constraints within the city. At Treasury Annex, a retained structure and tight site drove the use of a Schüco unitised façade; at the Tropical Fruit Warehouse, refurbished timber trusses support a ‘floating’ glass office volume; and at A&L Goodbody, a twin-skin façade required complex CFD analysis and innovative safety systems. The Salesforce building at Spencer Place showcased the largest façade project in Dublin to date, its suspended glass ‘veil’ requiring 3D design and jumbo Schüco unitised panels to improve performance. Coopers Cross demonstrated how orientation-specific shading and low-carbon aluminium can deliver measurable carbon savings, while the long-stalled Waterfront Citi towers underlined the gap between technical ambition and planning realities.

Afternoon panel discussion

The day’s second panel discussion, again chaired by Isabel Allen, brought together Tony Reddy, Denise Murray, Stephen O’Malley, Ali Grehan and Jonny McKenna to reflect on Ireland’s planning system and the delivery of sustainable communities. Reddy argued that the core flaw lies in planners acting as gatekeepers rather than vision-makers, contrasting the laissez-faire, site-by-site approach in Britain and Ireland with the long-term, consensus-based models seen in European cities such as Copenhagen. Murray stressed that while professionals often agree among themselves, the real challenge is communicating vision and value to the wider public – citing her practice’s work in small towns where communities are eager for holistic strategies rather than piecemeal fixes. O’Malley added that political leadership is critical, pointing to the coherence achieved in Manchester through strong mayoral powers, while also warning how political interference can derail strategic infrastructure.

From left to right: Stephen O’Malley, Jonny McKenna, Denise Murray, Ali Grehan, Tony Reddy, and Isabel Allen (photo: Jason Sayer).

The conversation turned to the undervaluing of city architects, with Grehan noting that even in Dublin the role lacks visibility and authority, and that architects’ contributions are often sidelined once economic growth returns. She argued that the housing crisis has sharpened the focus on numbers at the expense of quality, retrofit and liveability. McKenna concluded by observing that while policy sets out standards for housing, it leaves gaps around the social dimension, which architects must navigate creatively. He stressed the importance of designing for communities rather than just units, even if attempts at intergenerational housing or social cohesion are sometimes dismissed as “social engineering.”

Closing thoughts

Following the walking tour, which was led by Alucraft’s Shane Hall, delegates gathered at Henry J Lyons’ Pearce Street offices for a drinks reception. RIAI President Seán Mahon concluded proceedings by offering his reflections on the future of Irish cities. He praised the conference for addressing issues of national importance before turning to Ireland’s housing, infrastructure and population challenges. With the resources to respond effectively, he argued, the choice lies between repeating the short-termism of urban sprawl or adopting a long-term, quality-led approach that secures sustainable and liveable communities.

Mahon outlined three priorities from the RIAI’s new planning and development policy. First, he called for housing to be treated as infrastructure, supported by forward-looking strategies and early investment in transport and services. Second, he urged recognition of urban design as a distinct discipline within planning, shaping public spaces and lived experience through multidisciplinary collaboration. Finally, he stressed the importance of civic engagement, citing international models where active citizen participation has built trust and reduced delays. He closed by noting that Ireland’s challenges are significant but achievable if met with vision and coordinated action.

Reflections on the day