A pair of timber-framed eco-houses designed by Chance de Silva and Mike Nightingale demonstrate how to densify village conservation areas with verve and sensitivity.

Who gets to live in the historic villages of England’s beautiful countryside? Is it the landed gentry? Or City retirees, lawyers and other well paid professionals? What about key workers, shop assistants or refuse collectors – the millions earning a less-than-average salary? Eynsham in West Oxfordshire is one such historic village, with many of its 16th and 17th century buildings still intact, it lies at the heart of an area that competes with London and the south east for the highest concentration of managers, directors and senior officials nationwide. House prices are well above average and there’s a predominance of larger properties, exacerbating affordability. And like the rest of the country, it needs more affordable housing for the people that keep the region moving.

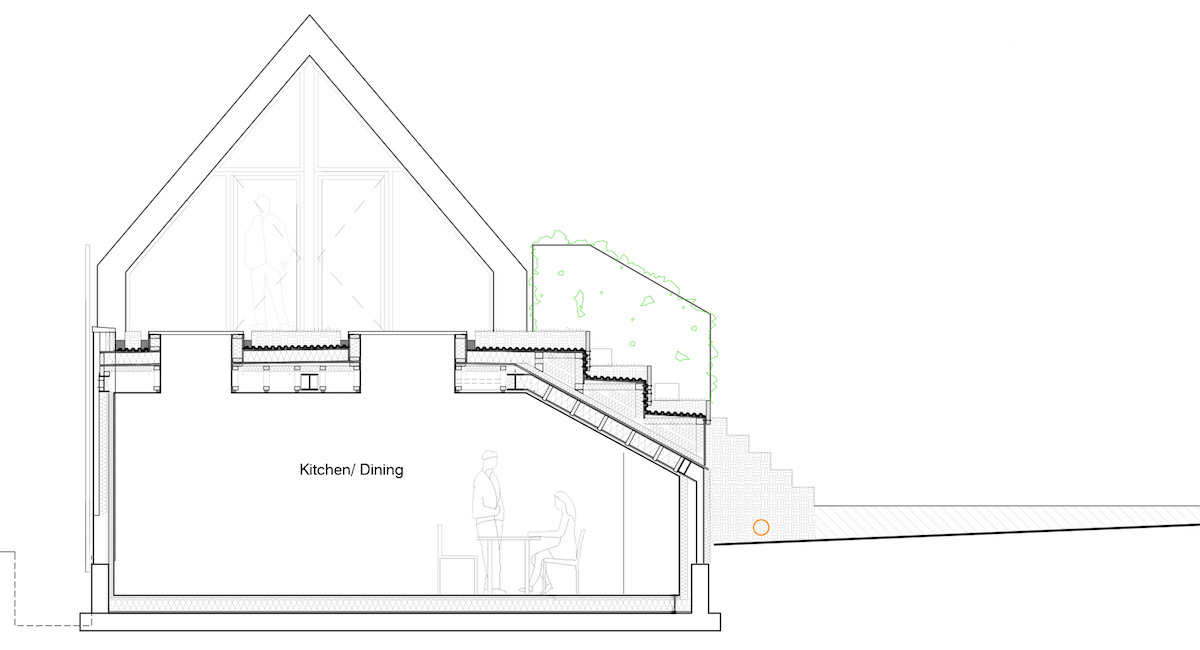

Ada Cottage is the smaller of the two new houses and incorporates a green roof terrace, which steps down to the ground-level garden and patio

Located four miles west of Oxford on the edge of the Green Belt, Eynsham has a growing population of around 4,500 people and is chock-a-block with high earners. The West Oxfordshire Local Plan and Eynsham’s own Neighbourhood Plan recognises this, emphasising social housing and homes for key workers, with a number of greenfield extensions planned, including a 2,200-home garden village to the north, and a site to the west for 900 homes.

On the fringes of Eynsham’s historic core however, a new development challenges the notion of greenfield extensions as the only answer to rural England’s housing shortage. London architect Chance de Silva’s ‘intensification’ of a 0.4 hectare plot (it has added two new timber-framed eco-homes to an existing two-home Edwardian estate on Oxford Road) demonstrates that if applied across the burgage plots of Eynsham, it could double the village’s density, slashing the development land take in the process. According to architect Mike Nightingale, who lives in the original villa with his partner Margherita (and their tenant in a neighbouring coach house), it has created “a multi-generational, carbon neutral, eco campus – setting an example to other baby boomers with a bit of land.”

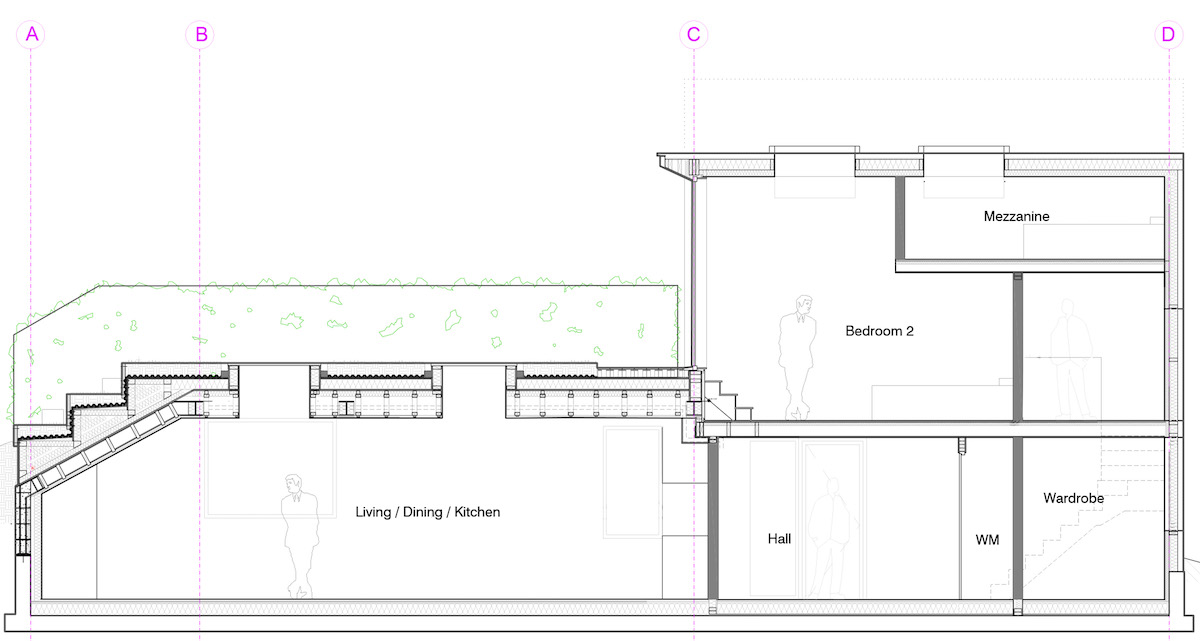

Ada Cottage ground and first-floor plans; sections

I catch my first glimpse of the scheme’s definitive steep-angled, larch-clad gables, set behind a beautiful stone wall, when a gap opens up between the mature roadside trees. Passing through the stone gate posts, the curve of the drive sets the gable end of the second house forward, so that both houses greet the visitor confidently. These are not stealth homes, embarrassed or hiding from view, but confident and comfortable in their Inspector Morse-like setting of garden walls, crunchy gravel and greenery.

I travelled to Eynsham with practice co-founder Steve Chance and when we meet Mike and Margherita, seated around a generous kitchen table piled high with homemade cakes perfect with cups of tea, it is evident that this is where the idea was first formed, then developed with the architect, and where inevitable tricksy negotiations took place too. Around this table, as I hear how they navigated archaeological digs together, unknown raised water tables (about which, more later) and impromptu design changes, I couldn’t help thinking that contractors could learn something here – about how the setting of their own on-site nerve centres, if they were comfy and friendly like this, might aid in the smooth running of what is so often a fraught experience.

The timber-framed structures employ larch cladding and cedar shingle roofs, alongside an array of sustainable technologies, including heat pumps and solar panels

Mike originally wanted to build three houses on the site: no mean feat given the handsome trees and conservation area status. The idea was to create two houses and a compact tree house, with low form factor, peaking out through the tree canopy, like a tower for a princess (conjuring images of Sverre Fehn’s Villa Busk, in my head at least). The planning department, who supported the principle of zero carbon homes on the site, rejected the tower (you’d see it from the approaching road) and slowly, three houses became two, lower in height, with a bigger footprint and higher in form factor, though no less visible in the immediate surroundings.

The new homes reflect the different needs of their occupants: Mike’s son and his partner and cat, in one named Ada Cottage, and Margherita’s son and family, including three children and a dog, in the other, dubbed The Bay Tree. The latter, to the west of the site, is the larger of the new homes. It clings to the boundary wall, its pitched roof resting just above it, and provides four bedrooms for mum, dad, a nine year old and twins aged 12 (three of them, for the kids, in the roof space). It also has a first-floor study area – for school homework and for mum, currently a Masters student.

The Bay Tree ground and first-floor plans; section

The young couple in Ada Cottage, a social worker and her engineering partner, mostly work from their new home. It has been designed to provide functional accommodation adapted to their needs: private space for her and tech-enabled space for his R&D work in electronics. It also includes a sleeping pod in the apex of the roof, and a green roof terrace that steps down to a ground-level garden (with chickens) – a delightful contrast with the traditional clipped lawn of the original Edwardian home.

Both houses are just the right size: not lavish but every space is accounted for. Entrance halls are generous, with space for boots, and in The Bay Tree, dog leads. Because there is no traditional ‘back door’ in the Bay Tree, the first-floor overhang provides an excellent porch, with a benchto sit and put your wellies on, and somewhere to leave muddy shoes. Light spills into the entrance hall from rooflights above the stairwell, which accommodates a seat – for reading perhaps, or might it be a look out perch for the dog?

The development occupies a 0.4 hectare Edwardian estate set on edge of Eynsham’s historic core

Still in the Bay Tree, spaces compress then open up, with the living room’s huge cathedral ceiling contrasting with the cosier, lowered ceiling of the kitchen and dining room. The roof-lit landing, bright and generous and designated a study space, also affords the children – who each have their own rooms – a communal play space.

It’s easy to forget that both of these airtight, timber-frame, larch-clad homes, with their cedar shingle roofs, house an array of kit – underfloor heating, MVHR, supply and return ducting, solar panels – in the bid to eliminate carbon emissions. Everything is cleverly squirrelled away in-between garden spaces, behind bathrooms and in cupboards, with nothing but the discreet ceiling air vent and wall mounted thermostat to signal that clever things are happening.

Throughout the project Mike acted as developer and intermediary – almost a client advisor – ensuring an open dialogue between the families involved with Chance de Silva and the contractor. Mike and Steve had worked together before, on an urban intensification project that saw them deliver three low-carbon homes in the grounds of a south London villa. This familiarity worked in their favour as there were proper pain-in-the-neck challenges to negotiate in Eynsham. The site, for instance, rises by 1.2 metres with planners insisting ground floors were dug into the slope. Chance de Silva had a constant tussle to achieve the accommodation needed by each family unit, against the demands of the case officer and the perceived impact of the development on the setting of the conservation area. Whatever the resulting compromises, the new homes and their steep roof pitches sit pretty well alongside the grade II-listed stone gables of the house across the road.

View looking towards Ada Cottage from The Bay Tree. The latter’s substantial first-floor overhang serves as a useful porch

So is ‘campus’ work a good place to live? I asked everyone from grandparents to grand-kids, and the answer was a resounding yes. It’s easy to be cynical though, of a ‘Grand Design’ project like this. You see them all around the country – the RAL 9017 aluminium window frame is usually a giveaway – but execution, too often, falls short. That could have happened here. The development was constructed over the Covid lockdown period, materials were scarce, delivery times were long and prices were rising. Slim-framed bespoke windows could have been replaced with something chunkier but cheaper. Yet such compromises don’t figure here. Gable ends – bound to be seen on Instagram – are crisp, slim and beautifully detailed. Corner windows survived the inevitable steel post threat, and where steel is needed, to tie the cathedral ceiling for example, it’s rod thin and elegant. And while each homes has its own south-facing garden, there is a sense too of neighbourhood here, where everyone lives within a single walled environment and shares cars, tools, tea, cake, and fresh eggs.

Image Caption Copy (optional)

Returning to the original purpose of this experiment, this is a beautifully executed, generous ‘Boomer’ offering to their children and grandchildren, which should age gracefully, due to the seemingly simple, clever detailing. It sets a great example of how to densify conservation areas with verve: district councils nervous of sprawl, and West Oxfordshire in particular as it moots options for key worker homes, take note. Likewise, housebuilders eyeing up the north and west of Eynsham.

Mike’s desire to reduce the site’s carbon footprint has now spread to the original house, where windows have been upgraded, wall, floor and roof insultation is set to be added, and the conundrum that will face of all of us is currently being digested: what do we replace our existing condensing gas boilers with? Finally, that raised water table. I said I’d come back to it. It came to light as the dig out to lower Ada Cottage was underway, and the slab was filling with water. Ever the optimist, having dealt with the construction requirements for the house, Mike dug a well – whose water now irrigates the entire compound. Genius!

Additional Images

Credits

Architect

Chance de Silva

Structural engineer

AKSWard

Services engineer

EnergyMyWay

Cost consultant

Richard Keat Associates

Cost management

Mike Nightingale and Jim Arbuckle

Main contractor

JJ Arbuckle Building

Clients

Mike and Margherita Nightingale