Foster + Partners has designed a museum of Roman antiquities for the city of Narbonne in the south of France. Alessandra Fanari enjoys the ambiguities of a sophisticated building where the distinction between architecture and exhibits is decidedly blurred.

At the entrance to the French city of Narbonne, Narbo Via, the museum of Roman antiquities, stands as a new civic monument and an eloquent celebration of the city’s prestigious past. Designed by Foster + Partners in collaboration with architect Jean Capia and museum consultant Studio Adrien Gardère, the museum contains galleries for permanent and temporary exhibitions, a multimedia education centre, auditorium, restaurant and bookshop, research, restoration and storage facilities, formal gardens, and an amphitheatre for outdoor performances. Its mission is to chart Narbonne’s history but also to bring the city’s remarkable collection of antiquities into a contemporary context, and to create a welcoming place for education and reflection; a space that is as much about future generations as it is about the past.

Under Roman rule Narbonne was an important Mediterranean port city and it remains a place of significant historical importance. In designing Narbo Via, the team has sought to make this heritage manifest by using materials and techniques specific to Roman architecture. Hence the building itself becomes part heritage, part exhibit, inviting the visitor to enter and contemplate its spaces and materiality as much as the content inside.

Watch a video tour of Narbo Via by Foster and Partner’s Spencer de Grey

The approach raises questions about the meaning and role of heritage in architecture. Modern architecture was founded on the reinterpretation of heritage, specifically Athenian and Roman classical universalism. Postmodernism countered this purist approach with a hybrid relativism, and its cheerful belief that we can learn as much from Las Vegas as from the masters of the distant past. Both schools suggest a different approach to the relationship between legibility and complexity, transparency and meaning.

Narbo Via sits – or flits – between these two traditions. An analysis of its architecture quickly reveals that its apparent legibility conceals a complexity of both form and meaning. Each element of the building, from the layout to the concrete to the ventilation system, is wrapped in a narrative that simultaneously references the past and present.

The planning draws on the typology of the archetypal Roman dwelling, adopting the fluidity between inside and outside and public and private spaces that characterised the Roman way of living. This fluidity is reappropriated to break down the institutional rigidity of traditional museum planning and to re-enforce the notion of museum as domus and domus as museum, in keeping with Foster + Partners’ ambition to redefine the museum as a sensual, warm environment that transforms perceptions of cultural space.

Materials were selected as much for their associations and meaning as for their practical attributes. The use of concrete – widely recognised as a symbol of the Romans’ materials expertise and used to form the basic structure of some of their most notable public buildings – is a case in point. This structural approach is underpinned by simplicity: solid, thermally insulated load-bearing walls support the roof with reinforced concrete double T-beams that span onto a grid of reinforced concrete beams. The glazing around the enclosure simply bolts directly into the concrete walls.

But there is an added layer of complexity in the execution of the coloured concrete walls, the first instance of Sirewall (Structural Insulated Rammed Earth) in France. Layers of dry-mixed concrete were tamped into place on site, resulting in stratification that calls to mind the idiosyncratic appearance of Roman architecture. This system also makes reference to the archeological nature of the museum and anchors the building in its surroundings. The use of aggregates from the local region combine to create a colour palette that recalls the earthy hues found in the natural landscape around Narbonne.

The environmental approach is inspired by Roman technology, with the majority of building services contained within a subterranean void. Cool air is pushed out at low level and at low velocity, allowing a smaller volume of air to be conditioned, maintaining a comfortable environment. The large spatial volumes formed by the high ceilings create a thermal flywheel effect that naturally pushes warm air upwards, from where it is exhausted. The concrete roof canopy provides thermal mass and extends beyond the walls to form a canopy that provides shading to the walkways around the museum.

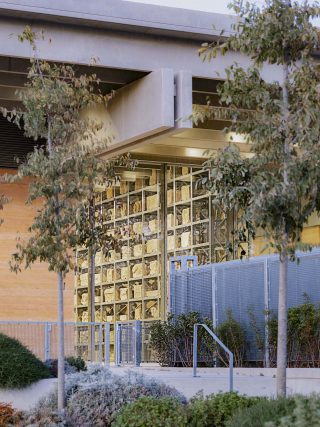

This canopy is punctuated by a long rooflight, allowing zenithal light to illuminate the ‘lapidary wall’ that forms the centrepiece of the museum. Imagined by Adrien Gardère as a monumental rack showcasing the collection of funerary stones, this lapidary wall embodies the soul of the Narbo as a dynamic, flexible space where spatial and temporal dimensions collide. The flexible display framework allows the reliefs to be easily reconfigured and used as an active tool for learning. The wall forms a natural boundary at the heart of the museum, an ‘in between’ space or passageway that physically separates the public galleries from the more private restoration spaces. Visitors can glimpse the work of the archaeologists and researchers through the wall’s mosaic of stone and light.

The constant play between light and shade, solid and void, old and new provides a series of unfolding vistas and juxtapositions that invite the viewer to consider or respond to both the architecture and exhibits in unexpected, often intuitive, ways. The narrative is deconstructed rather than linear, an invitation to take a second look, to think again, to observe things in different ways. The relationship between content and built environment is both complex and fluid. Architecture is stratified in archaeology, archaeology is deployed in museography. The building is not just a container for – but a means of engaging with – heritage.

By inviting the observer to engage with the creative process of contemplating the past, Narbo Via reframes the relationship between visitor and place. It provides an opportunity to look for clues and draw conclusions, to enjoy the opacity of history before it has been transformed into a fixed visitor experience.

In The Purloined Letter by Edgar Allan Poe, the detective amasses the signs left on the surface, clues that are neither visible nor hidden. Narbo Via doesn’t hide anything, but its clarity becomes spectral. For all of its apparent simplicity, there is an ambiguity, an open- ended ethereality, that invites the visitor to respond and interpret rather than read and observe. This replaces the notion of passive learning with the philosophical concept of poiesis, the activity by which a person brings something into being that did not exist before. Above all, it stands as a reminder that the real challenge of renewal is to continue the tradition of change while remaining sensitive to the spirit of the past.