One of the greatest Modernist buildings to emerge from the Olympics, Kenzo Tange’s Yoyogi National Gymnasium’s blend of Zen tranquillity and techno-monumentality connects Japan’s ancient past to its forward-thinking future.

The sloping temple-like roof, the tent pole-like posts, and the limpet-like plan hark back to traditional Japanese buildings and to natural forms (photo: IBA – stock.adobe.com)

This summer—barring another pandemic or other global cataclysm—the world’s attention will turn to Paris, where the XXXIII Olympiad is set to unfold. In what appears to be a new trend in urban planning around the Games (one which Los Angeles is preparing to follow in 2028), the French capital will not be building any new sports facilities specifically for the event; this marks a major break with Olympics past, which frequently featured extensive new construction to accommodate the various events and visitors descending on the host city. Given the tendency of such building campaigns to wreak varying levels of social, fiscal, and environmental havoc on the cities in question, the evolution towards the ‘no-build’ model is probably for the best. Yet it might be worthwhile to look back and consider how it was possible, at one point, to build Olympic architecture that stood the test of time.

On the podium of the greatest Modernist buildings to emerge from the Games, Kenzo Tange’s 1964 Yoyogi National Gymnasium in Tokyo stands shoulder-to-shoulder alongside the 1960 Stadio Flaminio in Rome and Munich’s Olympiastadion of 1972. Notably, while all three have been thoroughly canonised, the latter two tend to be more associated with their engineers (Pier Luigi Nervi and Frei Otto, respectively) than with their architects (Antonio Nervi and Günter Behnisch); never is Tange’s name omitted when speaking of the Gymnasium (its engineer, for the record: Yoshikatsu Tsuboi), and with the sole possible exception of his contemporaneous St Mary’s Cathedral, it is the Gymnasium that is mostly closely associated with Tange. For the future Pritzker Prize winner, and indeed for Japanese Modernism as a whole, the project opened the floodgates.

The sense of nihon shumi – ‘Japanese-ness of style’ reflects Tange’s career-long pursuit of a distinctly national architecture (photo: show999 – stock.adobe.com).

That was, in a sense, its objective. Designed to host aquatic events, the building and its nearby pendant—originally a basketball arena—occupy a walled campus that makes an unmistakable appeal to both the traditional building culture of Japan and the international current of postwar architecture. As seen straight on from the west, a doubled suspension cable rises precipitously from massive moorings, ascending to a trio of concrete posts while pulling half the roof up with it; the roof’s other half, yanked in identical fashion by a corresponding cable on the far side, is offset slightly to the north, giving the building a deceptively asymmetrical symmetry. The sloping, temple-like roof; the tent pole-like posts; the organism of the limpet-like plan: everything in the structure hearkens back to nature and to traditional architecture, while the zigzagging stone paths between the two structures give the environment an impressive admixture of Zen tranquillity and techno-monumentality. “Designs of purely arbitrary nature cannot be expected to last long,” Tange once said. No question, the design of Yoyogi was intended to be one for the ages, connecting Japan’s ancient past to its forward-thinking urban future.

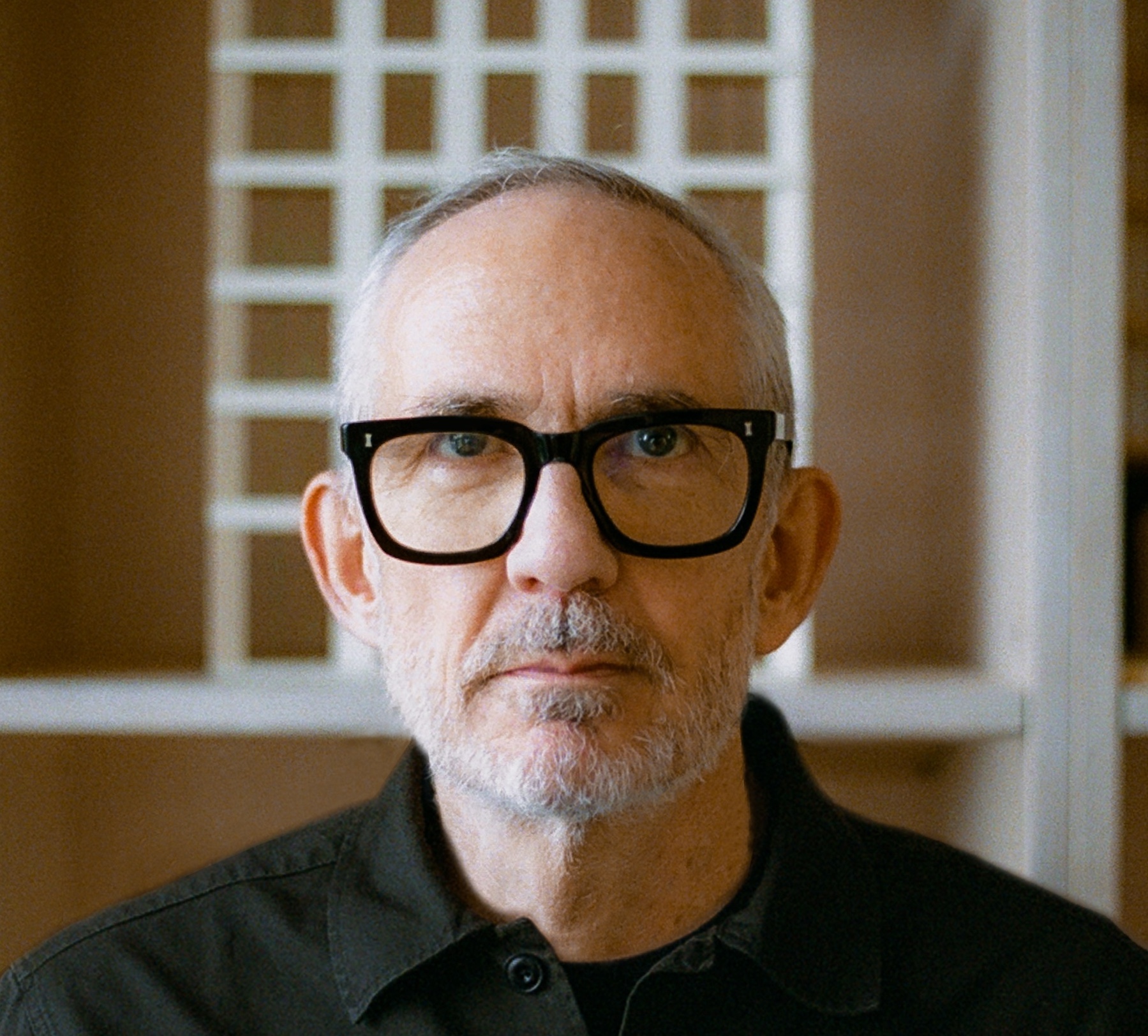

That had long been Tange’s goal— though its pursuit had led him into some murky waters. While he would become a prime figure in Japan’s post-war reconstruction, and clearly an adherent of the pacifistic ideology that accompanied it (evidence his 1955 Hiroshima Peace Memorial), the architect’s pre-war career under the imperial regime had seen him submit a proposal for a facility to house the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, the pseudo-federative body that Japan had created to give its expansionist project in China, Vietnam and elsewhere a veneer of respectability. Tange, then in graduate school, was already looking for a synthesis between Modern and pre- industrial modes of expression, and what survives of his competition entryis a variety of medieval Japanese palace compound hardened by a geometric planar composition and concrete materiality, almost anticipating thework of Louis Kahn but with a decidedly nativist, militarised overlay. In later years, Tange would renounce what he referred to as the ‘ethnic nationalism’ of his youth. But the sense of nihon shumi, the ‘Japanese-ness of style’ that he would perfect at Yoyogi, was not altogether divorced from that earlier pursuit for a distinctly national architecture.

What spares the gymnasium from such unsavoury connections, and what makes it such an exemplar of Olympic architecture, is that its rhetoric is so lacking in bombast, its bearing so decidedly modest, that it would be impossible for anybody to take offense. For all their grandeur, the buildings are not, really, all that large: 13,000 seats in the main building, another nine in its neighbour. From the street, they do not lord it over passersby, but sit invitingly within their stony greenswards, still popular destinations for local athletic events and valuable amenities for the surrounding community. The formal complexity that Tange endowed them with both conveys their indelible cultural identity, and effectively conceals it, opening the buildings up to the world who first came to play in them. Understatement, authenticity, and internationalism – if cities are once again to build good (or any) buildings for the Games, those three ingredients may well be key.