Bennetts Associates has completed a major renewal of Glasgow’s Citizens Theatre, a project more than a decade in the making. Rory Olcayto, who spent his formative years in Glasgow, visits a building that once bottled the city’s wild energy.

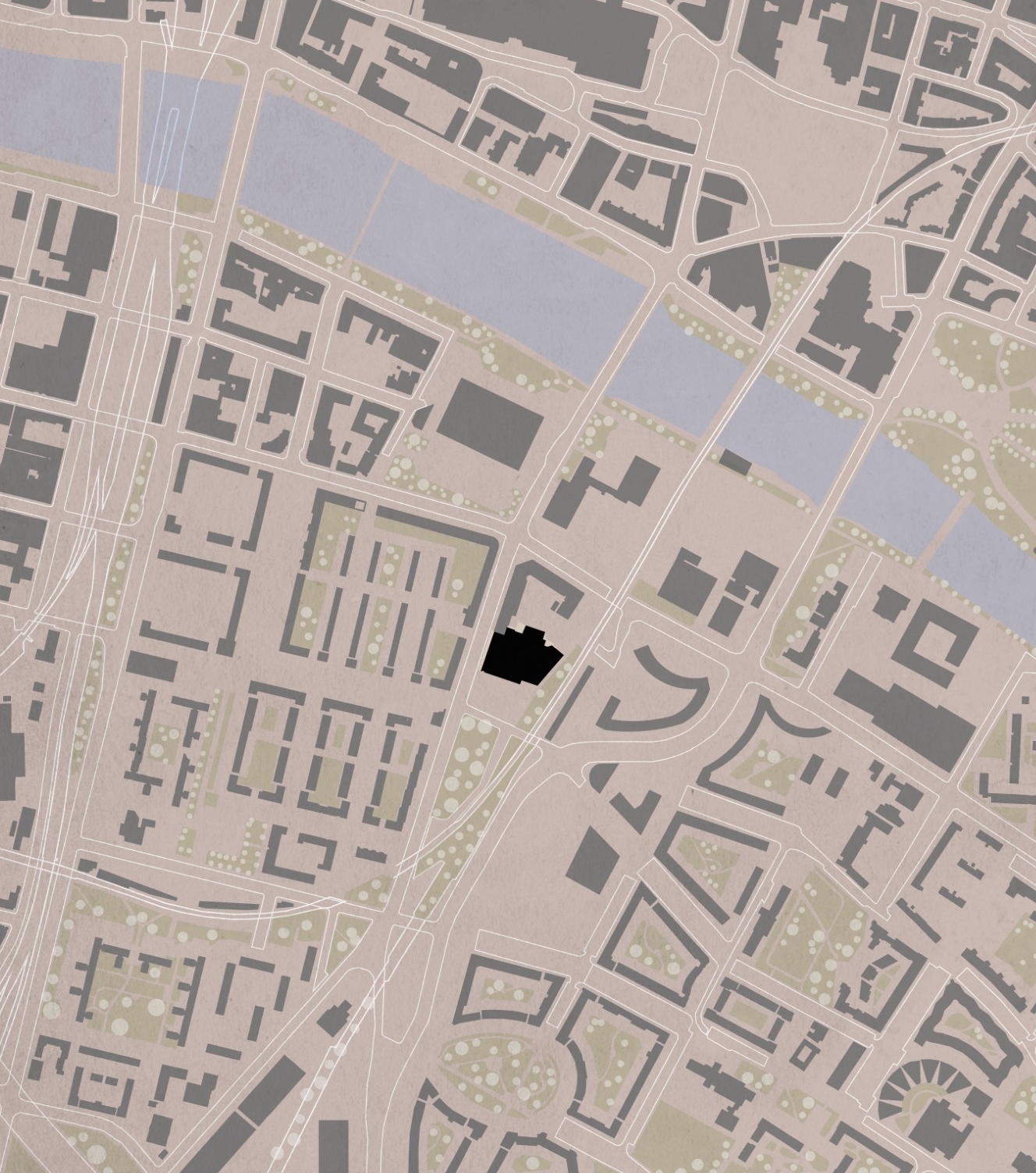

Before the mass clearances in the 1960s and ‘70s, Gorbals Cross, just south of the Clyde in Glasgow, was the focus of a dense, urban quarter. The tenements nearest the river were tightly packed and grim, but Gorbals Cross opened into a lively, almost theatrical scene. Several main thoroughfares converged here, their sandstone tenements pressing hard to the pavement, with shops and businesses at ground level. Tramlines curved and crossed at the junction, cables strung overhead, creating what looked and felt like an ‘urban room’. Monumental public buildings – theatres, churches, banks – a cast iron clock and drinking fountain, added grandeur to the bustle, lending the Cross more of the air of a European city than anything typically British. Photographs from the turn of the century could easily be mistaken for Barcelona, Milan, or Copenhagen.

Amid this stood the Royal Princess’s Theatre, the building that in postwar Glasgow would play host to the Citizens Theatre, a daring company which like the architecture all around it, had a much-admired, European flavour. Approaching it, you would have seen the handsome stone frontage that it once shared with the neighbouring Palace Theatre: a classical colonnade crowned with statues, by London Scottish sculptor John Mossman, of Shakespeare, Burns and the Muses. Gas lamps glowed against the soot-darkened sandstone, illuminating bill posters that promised melodrama, Shakespeare, opera, and panto. The theatre district here was a beacon of aspiration, offering spectacle and refinement at the edge of one of Europe’s toughest slums.

Root-and-branch retrofit

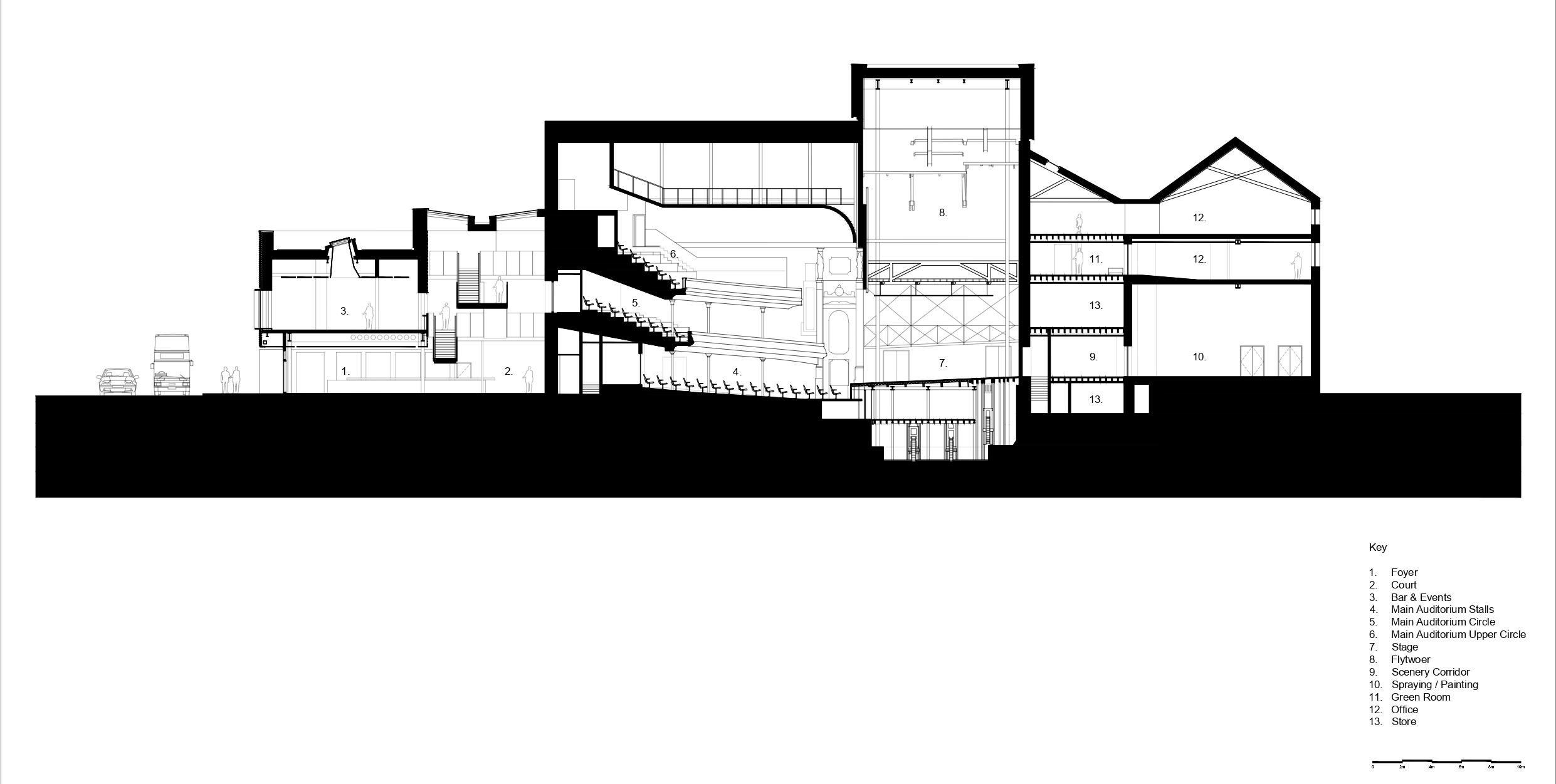

By the end of the 1970s, almost all of it had gone. Swept away by the city’s vast clearance programmes, only one hulking stone shed, previously hidden from view by the unifying facades of the Cross, remained: the Citizens Theatre. Against the odds, that survivor is still here in 2025, standing tall; taller now, in fact, thanks to Bennetts Associates’ root-and-branch retrofit and new flytower — as the theatre prepares to reopen after six years of stop-start construction.

And fifty years after it vanished, the Cross too, has begun to re-emerge, as the slow-burn regen commonly known as the New Gorbals, masterplanned and designed by many hands, and deep into its fourth decade, has taken hold of the district’s traditional heart. Now, as the Citizens Theatre re-opens, it sits at the centre of a residential neighbourhood dominated by hundreds of four-, five- and six-storey tenements. To those who know ‘the Citz’, this development is as significant as any upgrade of the building itself: for generations of Glasgow theatre-goers, a visit to the renowned Gorbals institution was typically likened to crossing over into East Berlin – bleak and thrilling in equal measure, a place defined by wide open spaces and crumbling, ruined architecture.

And now, for the first time in its long life, the theatre has been granted its own façade. When it was last overhauled in the late 1980s, a bland yellow brick frontage was created for a new block incorporating the procurator fiscal’s office next door as well the Citz front-of-house operations, with no differentiation between the two workplaces.

Even with this mind, Bennetts’ solution is unexpected; a floating Brutalist box in black brick with Citizens Theatre spelled out in giant, elegant, san-serif neon. Ironically, it resembles a sixties vision of the future, more akin to the Basil Spence futurist era of the Gorbals, than the Georgian and Victorian iterations, or the neo-tenemental version we have now. Real dramatic heft, however, is lent by the presence of Mossman’s salvaged statues, collaged across the roofline: it’s raw, visceral, a proud symbol of endurance in a district built, demolished and rebuilt over and over again.

Extremely hot and extremely cold

When Bennetts won the commission in 2012, the Citz, despite the ‘80s makeover, was still defined by the make-do and mend character that had seen it pull through as Glasgow vast and painful postwar demolitions. Its worn floors, quirky corridors, and patched roofs were part of its charm, giving it a lived-in feel that audiences and staff found endearing. Yet behind this character, the building had been struggling for years.

As Victorian Glasgow was being bulldozed into a Modernist city, this fortress-like theatre bottled the city’s wild energy.”

Visitors noticed the extremes. In winter, the auditorium could be bitterly cold, forcing audience members to wrap up in coats and scarves. In summer, heat would trap itself under a roof that could not ventilate effectively, leaving the space stifling. Rain was another constant: even after repeated repairs, leaks dripped onto the stage, soaking actors and equipment, while backstage areas were damp, poorly ventilated, and sometimes subject to raw sewage backing up beneath the floor.

Backstage and behind the public façade, the theatre’s layout compounded these problems. Narrow corridors, abrupt level changes, and a maze of stairs created obstacles to movement, while cramped studio spaces and offices offered little daylight or comfort. Toilets throughout the building were worn and inadequate. Despite these challenges, performers and staff continued to make the most of the space, relying on ingenuity and care to keep productions running. Undoing all this junkspace slop was, ultimately, the main task facing Bennetts.

Nevertheless, the Citz is more ‘place’ than ‘building’ and while the theatre’s fortitude is remarkable, so too is its cultural story. Few theatres anywhere have built up mythologies quite like it. For decades it thrived on scandal, daring, and invention. Trade unionists once got in free (50p for everyone else), a gesture that infuriated councillors. A Hamlet once staggered naked across the stage, dismissed by critics as “a gibbering oaf.” A Dracula was so gleefully explicit the Lord Provost demanded the directors be sacked, only for the show to play to packed houses.

Aladdin’s Cave

The theatre was also home to Glasgow’s first gay bar — one of the few places in the city serving alcohol on a Sunday night in the 1970s — and a launchpad for a dazzling roster of British talent: Pierce Brosnan, Ciarán Hinds, Rupert Everett, Sean Bean, Tim Roth, Gary Oldman, Robbie Coltrane, Alan Rickman, Tim Curry and Mark Rylance. As Everett, who joined in 1978, later recalled: “The company was being run by three maverick, rather highbrow, queens in a slum in Glasgow, putting on plays that were far-fetched and demanding. Because they didn’t patronise their audience, everyone adored it. It was one of the most extraordinary cultural events in the British postwar scene, frankly.”

Those “queens” were Giles Havergal, Philip Prowse, and Robert David MacDonald, who ran the theatre as a triumvirate from the early 1970s, harnessing shock and spectacle to win back audiences. Their timing was uncanny. As Victorian Glasgow was being bulldozed into a Modernist city, this fortress-like theatre bottled the city’s wild energy. Entering the Citz, Everett said, “off the streets of the Gorbals, which had very recently been completely destroyed, was like an Aladdin’s cave — an incredible experience.”

The Citz was founded and first based at the Athenaeum Theatre on Buchanan Street in 1943 under the direction of James Bridie, moving to the former Royal Princess’s Theatre two years later. Built in 1878, the building was once part of a compact, handsome city block owned and developed by John Morrison, whose firm built many of Glasgow’s great landmarks, including the City Chambers. But when the theatre next door — the Palace, Scotland’s largest — was demolished in 1977, much of the surrounding city fabric went with it, though alongside the salvaged Mossman statues, gaudier ornaments — elephants, exotic dancers — were extracted from the Palace interior.

Desolate and dangerous

I first visited in January 1985, with my parents and brother, to see Friedrich Schiller’s Mary Stuart — the version that imagines a meeting with Elizabeth I. I remember commanding performances and an impressive set: a towering, multi-storey construction. But the greater shock lay outside. The streets were desolate and felt dangerous. Across the road, new tower blocks — vast slabs of dark material that seemed to swallow daylight — already looked battered and worn. The theatre itself seemed oddly faceless, its auditorium set back from the street, reached only by a low corridor leading to the stage.

Still, I was hooked. And I kept returning: with my parents again, to see Richard III with Ciarán Hinds in 1988; to watch The Wasp Factory and Trainspotting in the early 1990s, when I was a student. It was during this time that I first encountered the salvaged bards, muses and gold-painted elephants, which enlivened the new foyer created during the ‘80s refurb. Later, in the 2000s, as a Gorbals resident, I made the most of the £1 locals’ ticket to catch modern classics like Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls with Daniela Nardini.

My most recent visit was only a fortnight ago for a tour with Bennetts Associates — just days before the Citizens reopened to the public, after six years of stop-start construction. Standing on Gorbals Street — quiet, empty almost of traffic and now augmented with a wide cycle lane — and gazing up a the uncanny Scarpa-inspired arrangement of ‘floating’ statues, comparisons with the past are hard to ignore. The old, shared façade, a seriously grand affair that captured the city’s international outlook at the height of its power, was composed of six fluted Doric columns at first-floor level, carrying an entablature and, above it, Mossman’s figures.

A new face

Bennetts’ façade speaks to a different Glasgow, one of provincial budgets and, curiously, given the city’s decorative heritage, an ornament-averse contractor culture. Clichéd or not, it does also speak of post-industrial resilience and reinvention, fronting perhaps the one building in the city that truly embodies this idea. It has a toughness too, that suit the Gorbals, trading ornamental grandeur for image-driven clarity. It works best at night, when the neon lettering glows against the concrete, the statues really do seem to hover, and you can see people gathering inside: we’re digital it says, but we’re ‘real’ too, right here: open, visible, civic in spirit; come in.

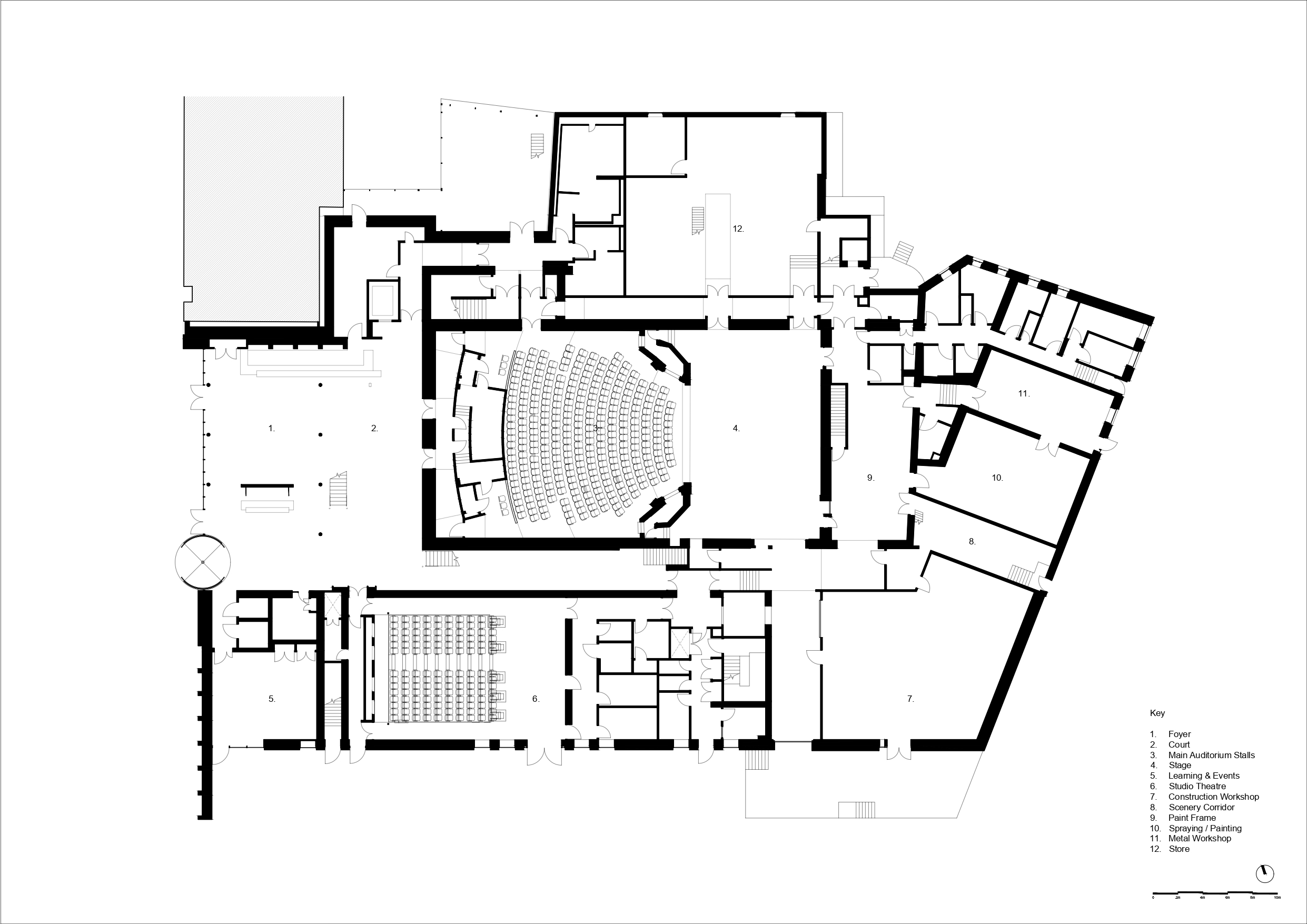

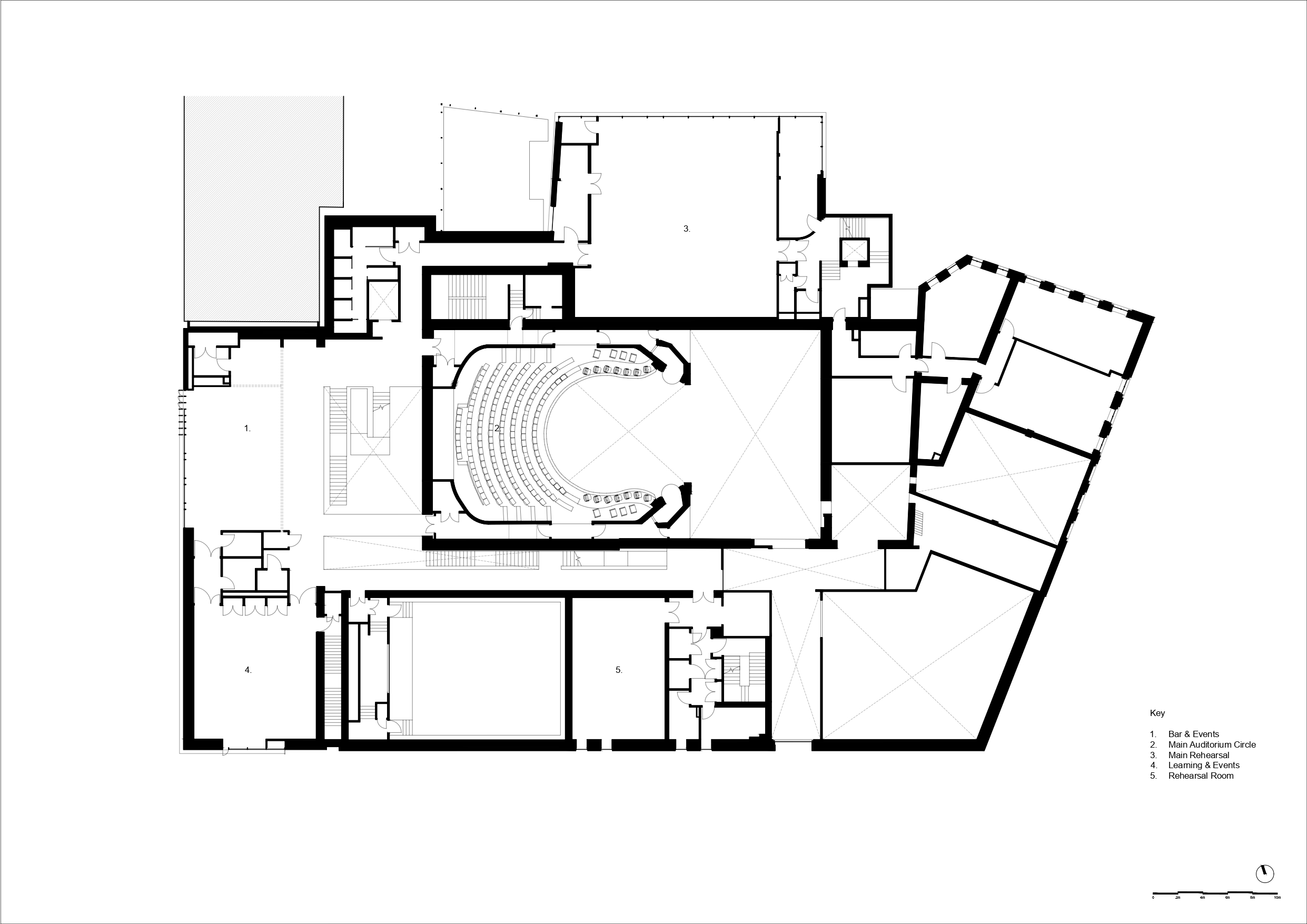

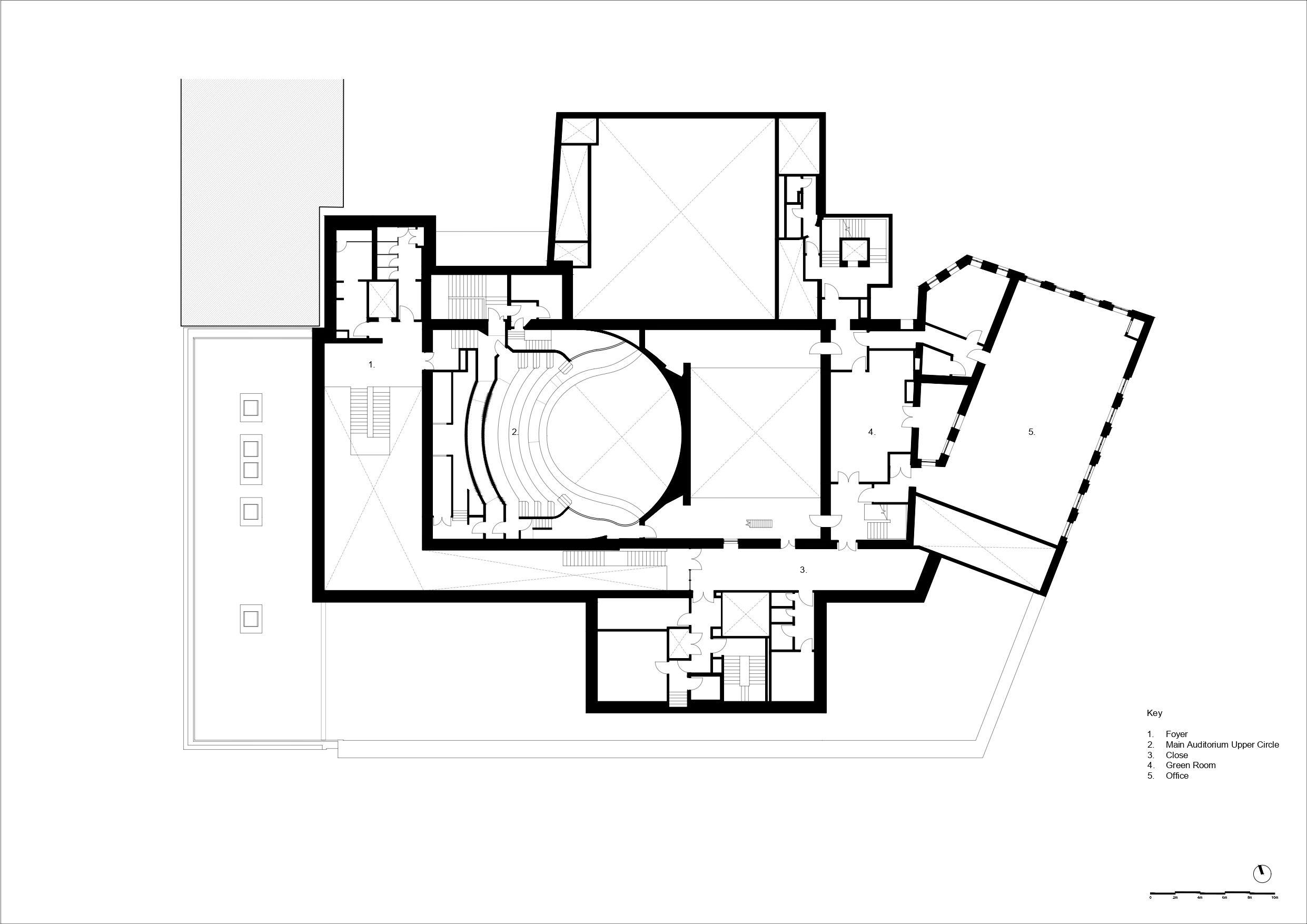

If the façade is weighted for Instagram, the interiors are for people — in the flesh. One of the most striking things about Bennetts’ renewal is how social it feels. The old foyers, cramped and awkward, are gone. In their place: broad, free-flowing spaces at street level, crammed with nooks, landings, benches, and bars. There’s a pink stair that winds its way up theatrically; balconies that let you look down — or across — at your fellow Glaswegians.

This is no accident. During my tour with the architects James Nelmes and Hannah Armitage, we alight on the topic of voyeurism — not in a seedy sense, more people-watching. They tell me that the new Citz is a building that acknowledges theatre begins before the lights dim. It starts with seeing who else is here, where they’re sitting, what they’re drinking. This was always the spirit of the Citz, particularly in its bohemian 1970s heyday. Now it’s built into the architecture.

What matters most is that the Citz feels like Glasgow.”

And crucially, it’s open. You don’t need a ticket to hang out here. There are learning spaces for school groups, windows into the workshops where sets and costumes are made, a sense of permeability between front and back of house. The mystery of theatre is still there but demystified just enough to make it clear: this is a civic resource as much as an art machine.

Urban archaeology

What makes the Citz unique, though, is its archaeology. Few theatres in Europe can boast such a palimpsest of spaces. Bennetts have exposed the historic paint frame, where backdrops are hand-painted on massive rollers. They’ve opened up the sub-stage machinery, still-working relics from 1878, visible again through glass. They’ve stripped back layers of 1980s refit to reveal arches, joist pockets, Victorian brick. The building wears its age unapologetically. This approach could easily have slipped into heritage fetishism. Instead, it feels right: the Citz has always been about rawness, about consciously not smoothing over rough edges.

Inside the main house, much is familiar. The red plush is back, the horseshoe balconies remain, the atmosphere intact. But it’s been carefully upgraded: sightlines improved, rakes adjusted, new concrete floors laid, timber structures fireproofed. The goal wasn’t reinvention but renewal, keeping the patina while making it work for the next fifty years.

Alongside, a new 150-seat studio theatre replaces a miserable old black-box. It’s fully flexible, with retractable seating, rigging grids, adaptable surfaces. This gives the Citz another scale to play with another social tool for community productions, experimental work, or just letting kids lark about on stage.

What matters most is that the Citz feels like Glasgow. Not because, like so much in the city, it is partially defined by demolition — the entire south and west wings were flattened. And not just because of its salty location. It’s more to do with attitude. It’s unpretentious, a bit rough, generous, sociable, outward-looking. The building today, post-Bennetts, genuinely embodies that spirit. You can come here to see a play, or just for a coffee. You can marvel at 19th-century machinery, or sit on the pink stair and watch the world go by. This is what architecture can do for a theatre: not compete with the performance but set the stage for social life.

How long?

Still, it took twelve years to get here. That’s way too long even if the renewal was stalled by Brexit, Covid, soaring inflation, and the aforementioned contractor culture. Skilled workers left, budgets ballooned, details slipped. But the project held together, largely thanks to the strength of the relationship between architect and client (the Citz more than the City Council, which ‘owns’ the institution).

Glasgow badly needed this project to be a success. With George Square dug up, the School of Art in ruins, libraries closing, cultural confidence low, the reopening of the Citz is more than just a local event. It’s a statement that the city still believes in itself as a place of culture, still believes in making space for people — everyone, that is — to gather. Bennetts, and its architects James and Hannah, take a bow.

Credits

Architect

Bennetts Associates

Main contractor

Kier Group plc

Theatre consultant

Theatreplan

Acoustics consultant

Sandy Brown

Structural engineer

Struer Consulting Engineers Ltd

Mechanical and engineering consultant

Max Fordham

Fire consultant

Atelier Ten

Conservation architect

Ian Parsons

Cost consultant

Turner & Townsend