At Fen Court, Eric Parry Architects shows how corporate architecture can regain its social and cultural role, says Louisa Hutton

The sheer chutzpah with which Eric Parry Architects has placed a vast shimmering crown on the top of its latest building in the City of London both surprises and intrigues. The blatant contrast that exists between the well-mannered, glazed terracotta-clad 11-storey building that sits so effortlessly in its context and the uninhibited swagger of the glassy structure above is not exactly what one might have expected from a practice that has established a reputation as the author of serious, finely conceived, highly contextual, beautifully crafted office buildings in the City.

However, it is not only the seductive nature of the building’s polychromatic crown that makes a highly unusual and positive addition to the cityscape – there are three further characteristics concerning its place in the city that equally convince: the sculpting and surface treatment of its body, the generosity given to the public realm at street level, and a sizeable public garden at roof level.

There is an assuredness with which Parry has created the lower building’s gently zig-zagged form. Approaching in either direction along Fenchurch Street the mass of Fen Court presents itself as four cranked planes that catch the light and one’s eye with pleasing alternate rhythm. On account of the double inflection, the pavement area has been increased which is both a significant plus for pedestrians and expands the street’s volume of air, now positively sculpted and held by the pair of shallow ‘V’s of the quadripartite facade.

A similar moment is found to the east on Billiter Street, where a single inverted ‘V’ again breaks the body into two. The Fenchurch Avenue facade has a subtler but nonetheless perceivable inflection, while the facade facing Fen Court is the only one whose articulation is a single outward crank that follows the line of the site. Through these inflections the building gains an idiosyncratic morphological language and a certain tautness. The systematic, rhythmic folding of the nine-sided body gives the whole an apparent lightness that belies its actual physical mass.

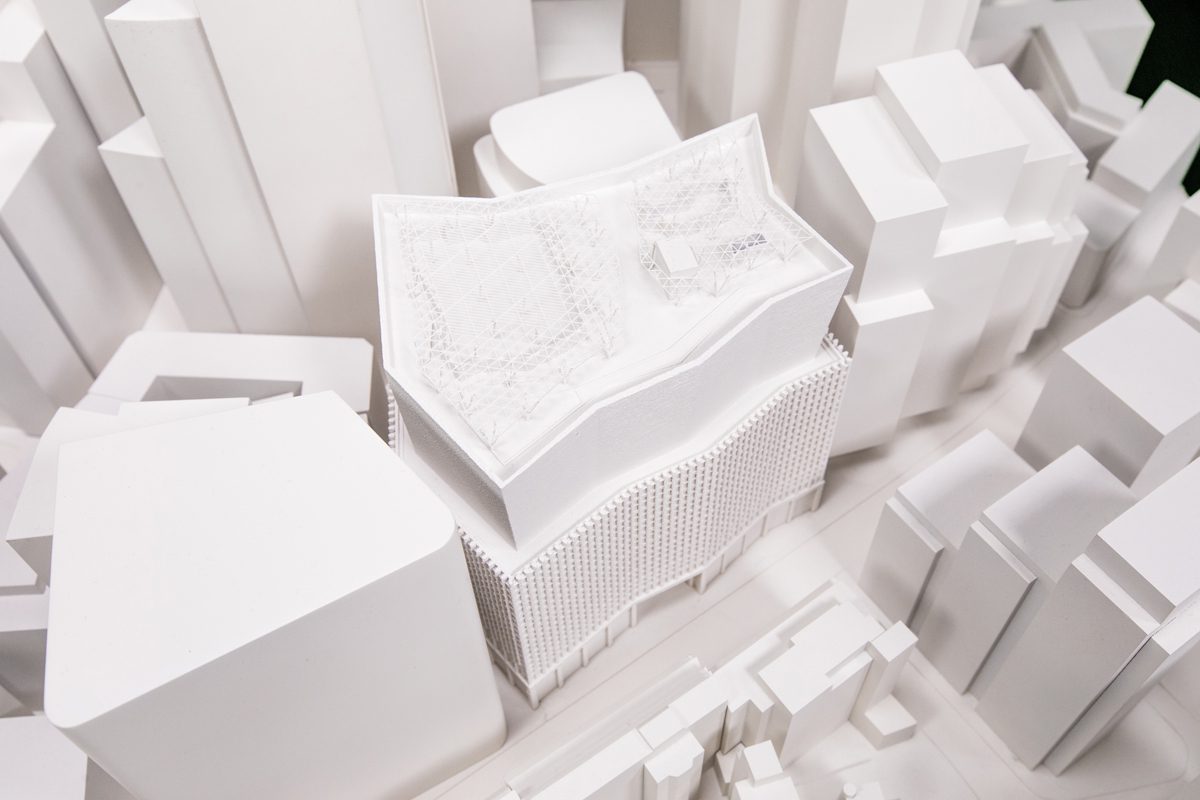

Ground floor plan. Fen Court comprises 10 Fenchurch Avenue, One Fen Court and 120 Fenchurch Street. The 39,670-square-metre building is on a 75- by 55-metre plot. It has a two-storey base and a new public passageway lined with retail, a main body with nine storeys of offices, and a glazed ‘crown’ providing four floors of offices and a restaurant. Inspiration for the building’s massing came from Hamburg’s deep-plan Chilehaus (Fritz Höger, 1924) whose form includes acute angles, punched courtyards and a celebration of sky in its use of copper roofs.

As is the case with many buildings in dense urban situations, Fen Court is nearly always approached anamorphically. So any three-dimensional treatment of the facades is first condensed and then released as one walks past. A fine-ribbed verticality is given by the pronounced array of engaged columns that rise uninterrupted from the second floor to form their own raw, spiky parapet at the eleventh. In between these, and somewhat set back, short, thick, shadow-creating horizontal brise-soleils are woven in like stitches.

This textile-like character invites a tactile response, and though it is well out of reach, one’s eyes are encouraged to roam. Drifting diagonally upwards and across the well-crafted solidity and texture of the facade they eventually land on the slippery face of the crown, whose glassy inclined planes offer no such physical certainties.

Sometimes disappearing into the sky and at others appearing as a brash neon-striped facetted vase, this five-storied polychromatic crown could hardly be more subversive. While the 11-storey tectonic base building is appropriately and politely sited, the crown with its bright, changing, glassy surfaces introduces a totally new game.

Ph; Grant Smith

EPA’s project underwent many iterations. A change of client resulted not only in the loss of a proposed atrium but also in the desire for a considerable increase in area. Many rounds of negotiations between architect, client and planners produced a quite brilliant bargain: more square metres – as long as they were in an independent volume that was set back from the main body – in exchange for a publicly-accessible roof terrace.

The inventiveness with which EPA has resolved this challenge is admirable. While the plan of the crown was derived from the form of the base building, its outward splay coupled with additional faceting introduces both formal independence and the offer of varying degrees of reflection. However, it was the bold decision to clothe this sharp-cornered volume in a candy-striped dress of dichroic glass – whose appearance changes according to light conditions and one’s angle of view – that brings its unmistakeable character and identity.

Model; development of the massing (phs: Sam Ainsworth/EPA).

The crown plainly seduces with its optical tease, one’s eye being mesmerically drawn to its ever-changing diaphanous surfaces of greens, blues and purples. Looking closer, the intriguing irritation of instability is further increased by an additional fuzziness given by the pinkish reflection of each dichroic film stripe on the inner surface of its glass cavity.

The crown seduces with its optical tease, one’s eye being mesmerically drawn to its ever-changing diaphanous surfaces of greens, blues and purples”

The pairing of the two buildings – the tectonic, material base and the crown with its oscillating ephemerality – awakens the age-old discussion concerning the traditional primacy of (intellectual) form over the (emotional) use of colour, or ‘disegno’ over ‘colore’ – as if the careful pencil drawings that Parry might have produced to describe the base have been challenged by an outbreak of digitally-generated watercolour.

Engaged columns are clad in an off-white glazed terracotta. Brise-soleils are made of a lightly textured metal whose colour changes from a purplish-green to a warm bronze at the upper levels. “The alternating rhythm of a somewhat unusual detailed articulation of the engaged columns reveals the tectonic logic of the body”, notes Louisa Hutton. “Only every second of the columns is structural on a tight three-metre grid”.

While there is an adventurous flirt right at the border of good taste (and while one would not want necessarily to encourage less able hands to experiment with dichroic glass) the clearly extroverted, attention-seeking nature of its use here can be fully justified. Celebrating the endurance of the sky that hovers over the ever-increasing density and mundane capital-chasing concerns of the mineral city below as it playfully toys with the light of day, the iridescent crown also announces the presence of the publicly accessible sky-garden.

The building is clearly divided into the classical tripartite: base, middle and top. At street level the generously proportioned double-storied concrete-clad frame defines the publicly accessible areas given over to retail as well as to the pair of office entrances: a grand one situated in the north-western corner at the junction of Fenchurch Avenue with Fen Court Garden and a smaller single-storied one just off Fenchurch Street.

A historic public passage called Hogarth Court that ran through the site needed to be retained. In its last incarnation it was curved, so one couldn’t see the daylight of the streets at either end. This has been revised so that on entering one has a clear view through to the opposing street, which draws one in. Both entrances have an exaggerated ‘fishtail’ plan, narrowing dramatically towards the centre. The same kind of squeeze occurs in section, so that an effect of forced perspective is given. The sensation of foreshortening is further dramatised by dark interior surfaces and neat, flush detailing, so the rectangles of seemingly hyper-real street life behind become particularly highlighted within their respective black frames. Walking into this passage from Fenchurch Street is a particularly somatic experience; distracted by the visuality of it all, one is surprised to find oneself walking uphill – the natural slope of the land being considerable.

A far greater surprise is the presence of an enormous illuminated soffit at the central space of the passage. Here, within a clearly defined volume that Parry likens to a banking hall, continuously changing images drench the space from above. Sometimes watery with natural or artificial colour, sometimes sky-filled vistas taken from the rooftop, sometimes rather generic views of tree canopies that will hopefully be replaced – these have all been selected by artists Vong Phaophanit and Claire Oboussier.

EPA ran a competition for the idea of a camera obscura that would relay images down from the top of the building into the heart of the public realm at street level. One doesn’t need to know that the scheme once promised a clear view to the sky from this point to appreciate the idea. Moreover, the animation – literally the filling with life – of a dark public space via an LED screen whose programme will change with the seasons is perhaps a more sophisticated attribute for this unusual public space than an atrium could ever have offered.

There is a particularly enjoyable theatricality to the ‘banking hall’ – the quotidian grind of our work-lives is suspended, as the shifting silhouettes of passers-by become the protagonists in a public performance.

Parry’s comparison of the central space to a banking hall recalls both the mercantile history of the site and its proportional similarity to rooms which “historically included expressive, at best gravity-defying ceilings – here transformed from the physical to the digital”, notes Louisa Hutton. “However, Fen Court’s threshold-less ‘banking hall’ for everyone is surely more accessible than any hall lying deep within the formidable institution of a bank.” “Reflective black glazed cladding of the interior, in combination with reflective qualities of the clear glass at the lift lobbies, adds spatial ambiguities and multiplies the perceived dimensions. Polished plaster soffits at either end harness blurred filmic-reflections of street life. A side view onto the pair of lift lobbies adds a further surprise to the experience of passing through.”

The surprise of the pedestrian’s experience in the ‘banking hall’ more than meets its match in the delight of the roof garden, which is easily reached via dedicated lifts. Finding oneself among the neighbouring towers – perhaps closer to the corpulence of the Walkie Talkie than one would rather be – and looking out over the skyline of London is both thrilling and fascinating. Seeing the immediate rooftops of neighbouring structures disfigured by ugly arrangements of plant, one regrets all those missed opportunities.

Planned by landscape architect Latz + Partner, the terrace offers a 360-degree walk around the perimeter, an impressive variety of sensual spaces, timber seating, abundant planting and haptic surfaces. The latter range from the modelled York stone paving, highly textured concrete walls, steel pergolas whose triangulated geometry echoes that of the crown, a long pool of water, various hedges and roses and 80 wisteria trees offering a huge shady canopy. A public restaurant situated on the floor below is accessible by stair or lift.

The 2,800-square-metre roof garden includes planting inspired by English country gardens, with espaliered fruit trees, a water feature and a perimeter walk that gives vistas of London’s skyline. Climbing Italian wisteria will soften a canopy designed to give shelter (model photo: Sam Ainsworth and EPA).

Apparently seven of the next 14 towers to be completed in the City will have public viewing galleries; would that even half of them might be as sophisticated and pleasurable as the roof garden at Fen Court.

This is a project with, as Parry puts it, civic soul. It displays an extraordinarily generous attitude towards both the physical and visual public realm that is all the more remarkable in consideration of the fact that the building was not conceived for a specific end user but as a speculative project.

While the quid pro quo barter mechanism of planning gain resulted in the felicity of a public roof terrace, it is the consummate intelligence and skill with which the architect has conceived and executed the entire scheme that makes the difference.

Not wanting to add yet another all-glass office building to the City, whose pathological accumulation of cold greennesses is seen by Parry as a kind of cadaverousness, the architect has created an ensemble that is clearly about enjoying life. One is naturally drawn to things that live: the main body of Fen Court has a clear corporality that we experience with our bodies while the whiteness of its glazed terracotta reflects light down to the street, the civic space of the ‘banking hall’ engages us both visually and emotionally with the staging of images on its soffit, the crown’s neon flicker bewitches us, and the generous, life-through-plants-and-people roof garden can be enjoyed up in the sky.

At last it has been proven that an alternative modus operandi is possible: corporate architecture can do the impossible and escape its lazy kowtowing to capitalist greed and the demands of the individual. It can serve the common good in its offer of inspiring buildings and the highest quality of civic space. In this way architecture, in regaining both its responsibility and its role as a cultural artefact, can encourage public life and social interaction and so support the very idea of the city.

Additional Images

Download Drawings

Credits

Architect

Eric Parry Architects

Landscape architects

Latz + Partner, Land Use Consultants (executive)

Visual artists

Vong Phaophanit and Claire Oboussier

Structural engineer

Arup

M&E, fire consultant

Waterman Group

Project manager

Core

Facade consultant

FMDC

Lighting

Paul Nulty

Acoustic consultant

Applied Acoustic Design

Quantity surveyor

Gleeds

Main contractor

Sir Robert McAlpine

Facade

Josef Gartner/Permasteelisa

Dichroic glass

Bischoff Glastechnik

Facade ceramics

NBK

Frames

Getjar (concrete), William Hare (steel)

Roof garden

Frosts

Roofing

Prater

Pergola structure

Littlehampton Welding

Water features

Fountains Direct

Paving

Marshalls

Garden substrate

Zeobon

Internal stone flooring

Szerelmey

Toilets

Celtic Contractors