Deyan Sudjic explains how his new biography of Boris Iofan, state architect to Joseph Stalin, shows how damaging it can be for a talented architect to come too close to power.

One of Iofan’s many designs for the unbuilt Palace of the Soviets.

Just as Vladimir Putin was seemingly handing over the Russian presidency to Dmitry Medvedev after his first term in office in 2008, in what we did not fully understand at that time was a parody of democracy, I found myself in Boris Iofan’s apartment, Stalin’s most prominent architect. It was on the top floor of Moscow’s famous House on the Embankment, the complex of 500 flats overlooking the Kremlin that Iofan had in 1929. It housed the party hierarchy in conditions of unmatched luxury. During the famine in Ukraine, engineered by Stalin’s forced collectivisation of the country’s peasants, residents had access to a private department store, cinema, hair salon and shooting range. During the purges, 800 of them were summarily shot dead, or died a little later of disease and hunger in the Gulags.

When I was there in 2008, the building was still topped by a giant rotating Mercedes star, as if to mock the illuminated red stars Stalin had impaled on the Kremlin’s spires. Iofan’s flat seemed little changed since his death in 1976. From its windows, I could see the golden domes of the new Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, a replica of the historic church destroyed by Stalin in 1931 to make room for the Palace of the Soviets. Iofan had watched the demolition of the church by dynamite from these windows, and later celebrated his victory over Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius in the competition to design the palace.

The apartment had the smell of years of neglect, a plastic shower curtain was stretched over boxes of his papers, but it did little to protect them from the dust being generated by workmen attempting to modernise the kitchen. Under his desk was a plaster maquette of Lenin, on a table there was another of a worker, one arm raised in a conscious paraphrase of the Statue of Liberty. It was the model for a giant steel statue Iofan put on top of the Soviet pavilion for the New York World’s Fair of 1939, in an incongruous tribute to the proletarian revolution in Queens. It was a reprise of his earlier design for the Paris Expo of 1937, where Iofan’s pavilion confronted Albert Speer’s German monolith.

Frank Lloyd Wright with Olga and Boris Iofan at a dinner during the first congress of the Soviet Academy of Architecture in June 1937. Their relationship continued during the war when Iofan joined the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, and appealed to Wright for help with its fundraising campaign.

Nearby were stacks of photograph albums; in one was an image of Iofan and his aristocratic half-Italian wife Olga, daughter of a Russian princess, taking tea with Frank Lloyd Wright at a conference in Moscow. Iofan looks like a sympathetic, sensitive-featured man in his mid forties, his hair combed back from a high forehead. His wife, with a cigarette in her hand and a briefcase under her arm, looks animated, an equal partner in the conversation with the notoriously egotistical Wright.

Iofan’s career is a cautionary lesson in how damaging it can be for a talented architect to come too close to power, especially for an architect negotiating an accommodation with tyranny. He was closer in his potential to Wallace Harrison, Nelson Rockefeller’s personal architect, than to a soaring genius such as Alvar Aalto, his close contemporaries in age. The latter, like Iofan, was born a subject of the Russian empire. But Iofan, unlike Harrison or Aalto, had to sacrifice that talent to stay alive. And also perhaps because Iofan was driven by the eternal instinct of the architect to build at any cost.

Most likely Iofan was always meant to win the Palace of the Soviets commission, less a competition than an architectural show trial. Nevertheless, his first submission was an impressive exercise in monumental rationalism. Stalin gave him the job, but only if he did exactly what he was told. Iofan’s own design was ditched, and within a few weeks the scheme had quadrupled in height, sprouting into a tower taller than the Empire State, topped by a gigantic representation of Lenin. If it had been completed, Lenin’s index finger would have been 15 feet long.

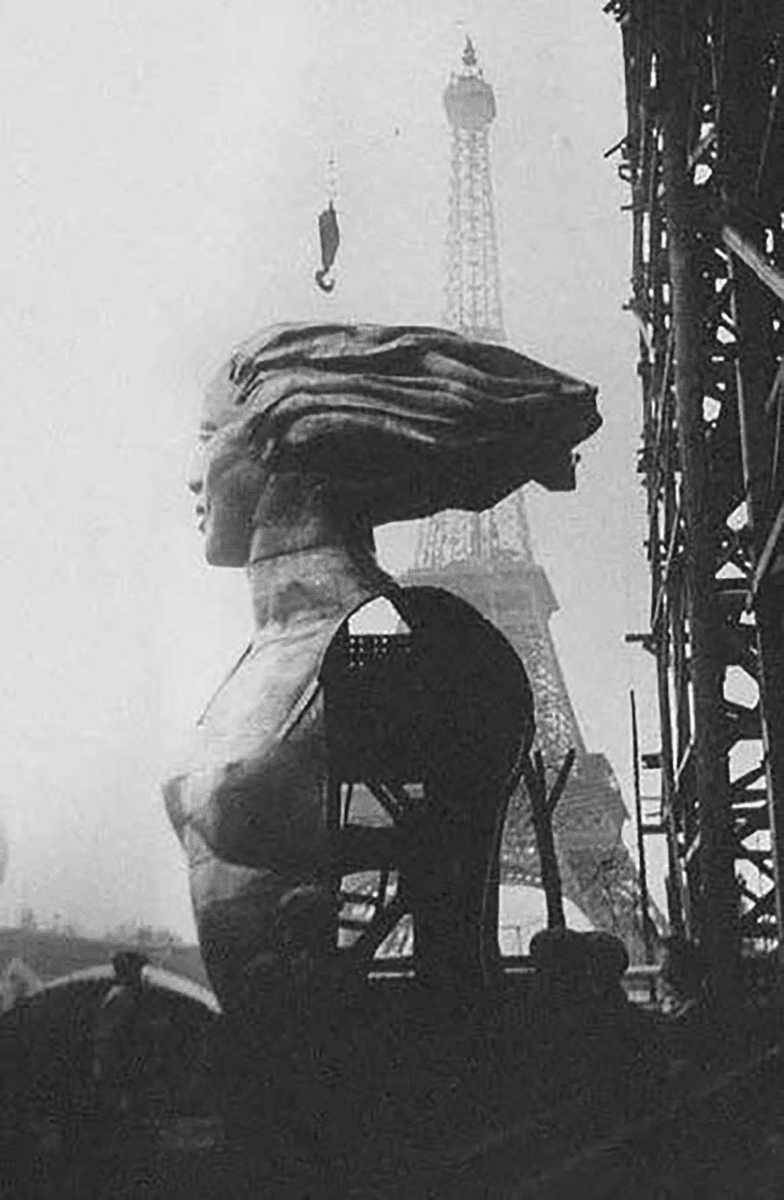

Iofan’s Soviet Pavilion under construction for the Paris Expo of 1937, with Vera Mukhina’s huge sculpture as its high point.

After this visit, I began trying to learn as much as I could about what had gone on in Iofan’s mind as he saw his work turned into a monstrous tribute to Stalin. Iofan grew up in Odessa and witnessed the horrific pogrom of 1905. He studied architecture in Rome, a victim of the quotas imposed on Jews at the Imperial Academy in St Petersburg.

In Italy, he worked for Mussolini’s favoured town planner Armando Brasini and married Olga. They both joined the Communist party. He stayed for 10 years, returning in 1924 when he was persuaded to go home by Alexi Rykov, Lenin’s nominal successor as prime minister, who promised him the chance to take part in the reconstruction of the country after the civil war. Rykov and Iofan became close friends and Iofan was awarded the House on the Embankment job without a competition after he unrolled his sketches on the floor of Rykov’s apartment in the Kremlin Miraculously, Iofan survived Rykov’s torture and execution by Stalin. From his flat, he watched a perfect circle of giant cranes rise on the palace’s construction site like a hollow crown in a futile struggle to drag his reluctant building up from the mud. Later still, he saw his 25-year-long struggle to realise what would have been the largest building in the world drowned by Stalin’s successor, Nikita Kruschev, who had the foundation pit for the palace turned into a huge open air swimming pool.

Iofan’s story still touches us partly because of his ability to survive the worst of times, when so many of his contemporaries did not. But it also illustrates the price of working for the monstrous Stalin. His career is a precise reflection of all the compromises architects make with power.

We should be thankful that for the past half century most creative individuals have not had to face such a brutally sharp choice as the one identified by George Orwell, who suggested that “while certain arts, or half arts such as architecture might even prosper under tyranny, for the writer the only choice is tyranny or death”. When Iofan was denounced as a rootless cosmopolitan in 1949, and sacked from the job of building Moscow University, he was reduced to humiliating himself with a series of fruitless letters begging Stalin for work.

Lanfranco Cirillo, who may or may not be a qualified architect, does claim to have designed, built, and furnished the bathetic Versailles-on-the-Black Sea palace apparently intended for the exclusive use of Vladimir Putin. Cirillo certainly seems to have learned one lesson from his predecessor. He left the country, despite reportedly facing tax evasion charges at home in Italy. He was working in Dubai where Der Spiegel found him last year.

But a better lesson is the courage of those who did more than Iofan to face up to Stalin, and those who now have the courage to face down Vladimir Putin. Piotr Kapitsa for example, one of Iofan’s clients, a brilliant physicist kidnapped by Stalin and prevented from returning to his laboratory in Cambridge. Iofan designed his institute in Moscow. When Kapitsa’s deputy at his institute was arrested by the KGB who claimed he was a Nazi spy, he successfully demanded that Stalin release him.

That’s courage of a kind like that of the extraordinary bravery of those Russians protesting in the streets today against Putin’s war. Its courage that we should learn from, admire, and hope that we are never called upon to show ourselves.

‘Stalin’s Architect: Power and Survival in Moscow’ by Deyan Sudjic (Thames & Hudson, 320pp, £30) is published on 28 April