John Pardey revisits de Blacam & Meagher’s Chapel of Reconciliation at Knock – a landmark of 20th century Irish Architecture – tracing its pilgrimage roots, profound materiality, and overarching influence on a new generation of Irish architects.

This article is part of a monthly series of short essays on some of the greatest buildings of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Read John Pardey’s introduction to the series here.

To become an architect you need to know how buildings evolved.“

— Shane de Blacam

In 1879 reports of ‘strange appearances in a small Irish village’ swept across the country. Featured in the media, including London’s Times, and as far across the Atlantic as Chicago: a small group had witnessed apparitions of various saints, angels and the Virgin Mary in the village of Knock, County Mayo. Over time the village became a pilgrimage destination and today receives between one and one and a half million people each year, making it one of the principal shrines in the world. It has five churches hosting Pilgrimages, masses and confessionals for Catholics, along with a hotel, caravan park, café, and since 1986, an airport.

In 1989, the young Dublin-based practice of de Blacam & Meagher won a competition held by the Archbishop of Tuam, Most Rev. Joseph Cassidy, for the Chapel of Reconciliation at Knock. Shane de Blacam had completed his studies in Pennsylvania and had worked in the office of Louis Kahn, while John Meagher had completed his studies in Helsinki, so had fallen under the spell of Aalto, Lewerentz and Asplund. The architects had joined forces while teaching at University College Dublin (UCD), and their joint influences were to provide a foundation for their own work, lending a preference for natural materials, clear forms and rigorous geometry.

Combining practice and teaching at UCD, de Blacam and Meagher were to nurture a new generation of architects in Ireland that were to have significant impact on not just the city of Dublin, but on Irish architecture. This began with a competition launched in 1991 by the Taoiseach Charles Haughey under the name of the Temple Bar Framework Plan, which coincided with Dublin’s designation as the European City of Culture so received funding from the European Regional Development Fund. The competition was won by a group of de Blacam and Meagher’s former students and colleagues from UCD – including the future RIBA gold Medallists O’Donnell & Tuomey and Grafton Architects – who had formed a consortium named ‘Group 91’. Their winning scheme was implemented and completed in 1998, transforming a declining city centre with a series of discrete interventions, making new streets, squares and cultural hubs while respecting the existing fabric of the city. Yvonne Farrell of Group 91 (now of Grafton Architects) wrote that, ‘You need cracks in the system, you need low rents, you need people in cities.’ echoing Jane Jacobs’ seminal The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

Some ten years before the Knock Chapel win, de Blacam & Meagher had built a modest church in Firhouse, a south-west suburb of Dublin. Like all their later works, this building was based on traditional precedents, such as a walled garden, or cloister. The enclosing walls were built in concrete blockwork and the space occupied by a single-storey, framed structure, a cruciform plan with glazed walls opening out onto four planted courtyards, each planted for a different season. The four-square plan is extended at one end by a further bay, to create the cross. The simplicity and clarity of the plan and the diagonal cross-beams overhead to each bay certainly recalls of Khan’s structural geometry.

Their Knock Chapel was on a far larger scale, with a brief to accommodate 500 people and 60 priests at a single service – it is a building of some 2,100 square metres. The slightly rectangular plan is roughly 40 x 45 metres and single storey, with raised rectangular section in the middle, crowned by a tall lantern.

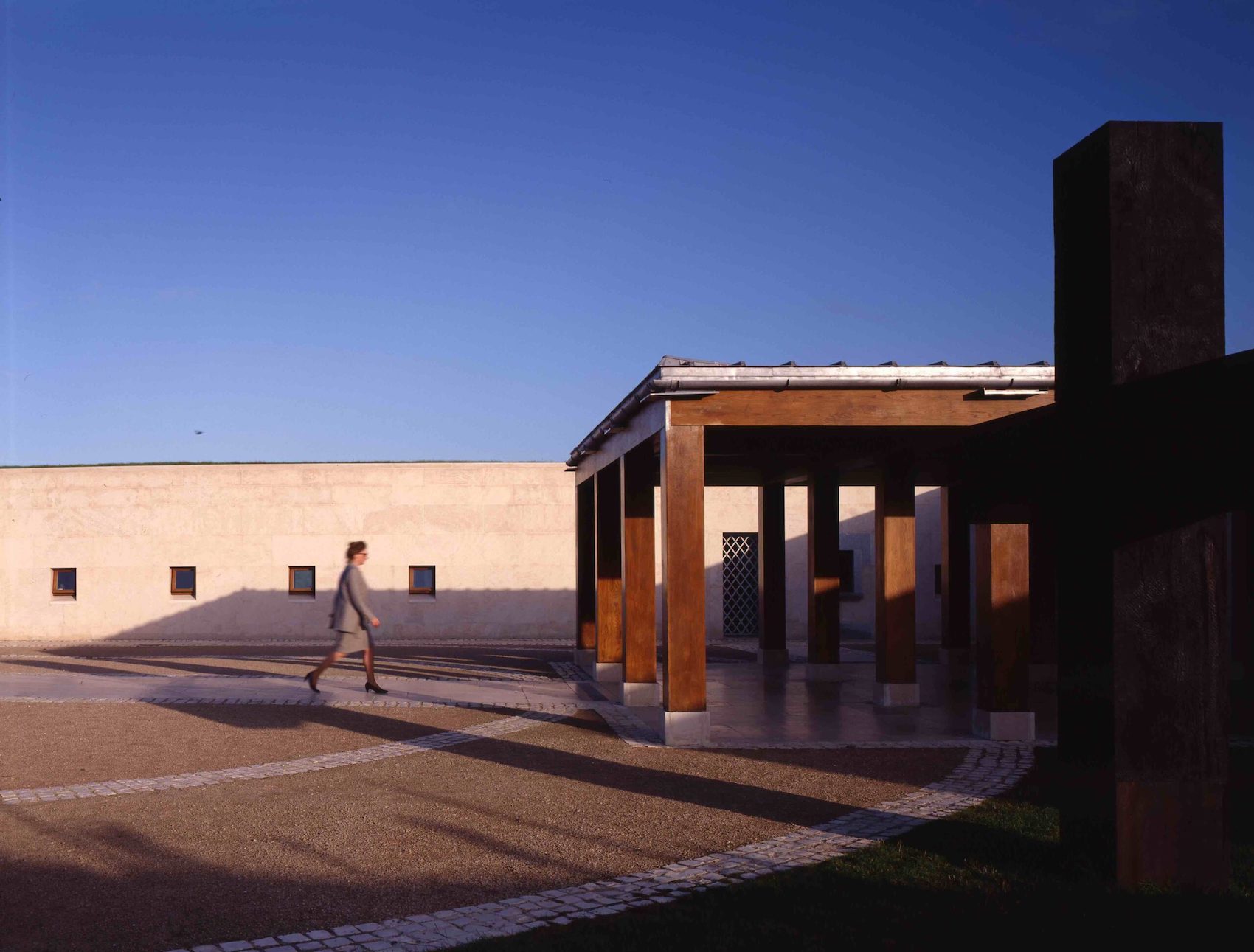

The whole building is set into a fold in the land, nestled into the landscape. A gravelled processional square, incised by a double circle formed in granite setts is framed on two sides by limestone-clad walls and embraced by an earth bailey that opens onto the front of the Chapel signed by an entrance portico. A giant carbonised oak cross, made by sculptor Michael Warren sits to the right. This 9-square portico formed in solid, laminated oak columns and beams, and capped in lead-coated steel, leans heavily on Asplund’s Woodland crematorium.

The Chapel at Knock is profound, and must vie as the most important building of the 20th century in Ireland.”

Inside, the entrance sits off-axis to the nave within the chapel and there is no overt ecclesiastical and decorative symbolism, rather a calm backdrop of natural materials – limestone and oak – and the play of light from above.

The side walls contain a staggering 50 confessional rooms, while a run of 10 reconciliation rooms line the rear, all served by an ambulatory that surrounds the nave. This rises up to double-height sitting upon a colonnade of sturdy oak columns supporting deep, red oxide painted ‘I’ beams that John Meagher had seen in Lewerentz’s 1966 Klippan church. The head of the columns have strengthening webs that form a cross – tree and cross a central symbol of both Old and New Testaments. Even deeper steel beams criss-cross the colonnade and culminate in a giant lantern, another nine-square cube formed in oak and clear glass, some 12 metres high.

The original hard wood and glass lantern has been recently replaced with a steel and glass cube; “a happy update” says Shane de Blacam, “clarifying the hollow ground beneath the rising ground to the rear surrounded by plain cruciform telegraph poles painted white forming a processional route about the pilgrimage site.”

The lantern sits above the sanctuary which is backed by a reredos, built as a steel-framed triptych covered in polished limestone, with a tabernacle of bleached oak with an inlaid gold cross.

The change of ceiling heights within the Chapel and its exposed structure overhead forms a powerful array of crosses that culminate in the celestial light of the lantern.

The stone and steel structure are counterpointed by beautifully detailed joinery and furniture – the elegant pew benches could have come from Kahn, or Scandinavia – an attention to detail that was to become a hallmark of the practice’s later work.

The Chapel at Knock is profound, and must vie as the most important building of the 20th century in Ireland. It provides a testimonial to the influence of the century’s great architects, from Asplund to Kahn. Shane de Blacam & John Meagher can rightly be seen as the godfathers to an Irish architectural renaissance, giving rise to a new generation of architects that have a strong claim to be some of the best in the world today.