At an Architecture Today event at the Schüco showroom in London, architects, engineers and façade specialists behind two major projects – 76 Southbank and Belfast Grand Central Station – discussed what successful collaboration looks like when delivering large, complex buildings in demanding urban contexts.

What does effective collaboration look like when projects grow in scale, complexity and public visibility? How do teams maintain architectural ambition while responding to regulatory, structural and environmental constraints? These were the questions explored at Collaborative practice: Delivering landmark projects, held at the Schüco showroom in London on 11 February 2026, where multidisciplinary teams presented two recent schemes shaped by intensive coordination and technical problem-solving.

The evening opened with remarks from Architecture Today editor Isabel Allen, who framed the discussion around the tension between technical demands and design intent on major projects, before Dan Gleeson of Schüco outlined the company’s growing focus on refurbishment, façade remediation and low-carbon aluminium systems as part of wider industry moves towards extending the life of existing buildings.

Stefan Rust from Allford Hall Monaghan Morris presenting 76 Southbank.

76 Southbank – Allford Hall Monaghan Morris

The first presentation, delivered by Stefan Rust of Allford Hall Monaghan Morris (AHMM) with input from project partners, examined the transformation of 76 Southbank, the former IBM headquarters designed by Sir Denys Lasdun and completed in 1983.

Rust traced the building’s historical context, describing how the South Bank evolved from an industrial landscape of wharves and timber yards into a cultural quarter shaped by post-war development, including the National Theatre and Southbank Centre. The IBM building formed part of this later phase but suffered from poor environmental performance, limited public engagement and office layouts that no longer met contemporary expectations.

AHMM’s brief was to refurbish and extend the structure, increasing floor area by around 50 per cent while retaining the original concrete frame and characteristic precast façade panels. The project introduced a new street-level entrance, extended floorplates and an additional storey, alongside significant improvements in daylighting, accessibility and environmental performance.

Much of the presentation focused on the technical challenges of working with an existing structure. Surveys carried out after strip-out revealed differential settlement across the 140-metre-long building, requiring careful coordination of façade tolerances and structural interventions. Testing also showed that existing concrete and foundations performed better than expected, allowing engineers to reduce strengthening works and avoid unnecessary carbon expenditure.

The façade renewal was another major area of collaboration. Original glazing systems could not accommodate modern double-glazed units, requiring a new curtain wall designed to align with precast panels while accommodating structural movement. Ultra-low-carbon aluminium profiles were used for the first time in the UK on this project, contributing significant embodied-carbon savings compared with conventional systems.

Here, a lot of the work depended on careful investigation of the existing structure. Surveys carried out after strip-out revealed unexpected settlement across the building. Rust recalled how digital modelling showed that “a third of the building was sloping by about 70 millimetres,” requiring careful coordination of façade tolerances and structural interventions.

Among the most striking discoveries during the project was how little the terraces had been used. “IBM didn’t want people getting out, going out, in case they fell,” Rust explained, noting that original balustrade heights no longer met modern regulations. At the same time, the building itself performed poorly: it was “all single-glazed, minimal amounts of insulation, and it was all running on gas as well — so performing terribly for the environment.”

Rust also highlighted the importance of reuse and material continuity. Precast panels were carefully removed, repaired and reinstalled, while new panels were fabricated using granite from the original quarry to maintain visual consistency. Internally, exposed concrete and reclaimed materials were paired with timber finishes to soften the building’s character and create contemporary office space.

For Rust, the project demonstrates how even challenging modernist buildings can be successfully adapted. The completed scheme, he suggested, shows that refurbishment can combine conservation, sustainability and commercial viability within a single strategy.

Arup’s Simon Brimble discussing the security demands of the project brief.

Belfast Grand Central Station – John McAslan + Partners, Arup and Williaam Cox

The second case study shifted from refurbishment to infrastructure, with Colin Bennie of John McAslan + Partners presenting Belfast Grand Central Station, supported by Simon Brimble of Arup and Brendan Barrett of façade specialist Williaam Cox.

Bennie described the long gestation of the project, which began with a competition win in 2014. “That’s how long these projects take,” he observed. “Transport is not a quick game.” The new station is designed to accommodate up to 20 million passengers annually by 2040 and forms part of a wider regeneration strategy for the surrounding district.

The architectural concept draws on Belfast’s industrial heritage, particularly the mills that once lined the city’s rivers. Bennie explained that these precedents informed a design characterised by large, daylit volumes and clear structural expression. The concourse is organised as a single-level, step-free space, allowing passengers to orient themselves visually. “All the information you need is available to you before you’ve even got into the building,” he said, emphasising the importance of intuitive wayfinding.

Beyond its functional role, Bennie argued that the building has a broader civic significance. Recalling an early encounter with a member of the public, he said: “The first day of operation… a lady came up to me and said, ‘Is this for us?’” For Bennie, such reactions underline the transformative impact that major infrastructure can have on cities and communities.

Simon Brimble of Arup described how security requirements shaped the project from the outset. “It requires a high degree of collaboration all the way through the project,” he said, explaining that the team worked closely with security stakeholders, operators and designers to integrate blast mitigation and secure-by-design principles.

Brimble also highlighted the challenge of reconciling these requirements with the architectural ambition for a light-filled building. “The glazing and the size of the glazing… some might consider to be problematic,” he noted, but through engineering and coordination the team was able to “provide a blast engineered solution” that preserved the openness of the space.

For façade contractor Brendan Barrett, the complexity of the project lay in making highly engineered systems appear simple. “The amount of engineering that we’ve gone through to make it look like big, simple curtain wall… that is the testament to this job,” he said.

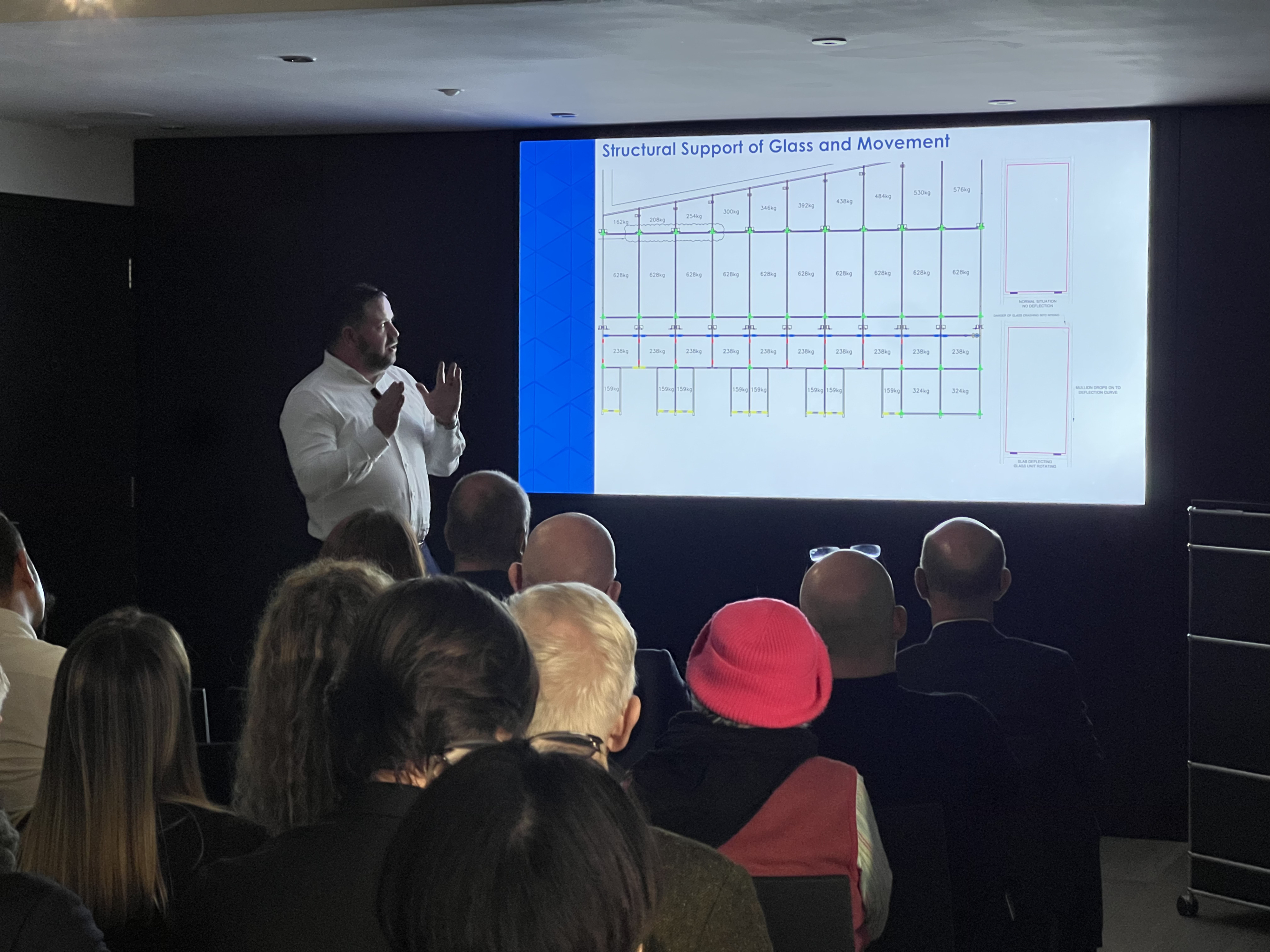

The intricacies of the façade build-up outlined by Brendan Barrett of Williaam Cox.

Barrett provided a detailed account of the façade engineering: a single curtain-wall elevation measuring 147 metres in length required accommodation of significant thermal movement, bespoke structural solutions around large door openings, and integrated drainage systems within visually minimal profiles. Some individual glass panels weighed more than 600 kilograms, demanding precise structural coordination and installation strategies.

Barrett also described some of the technical challenges involved, including accommodating thermal movement across long elevations and supporting very large panes of glass. Yet, he argued, the real success of the project is measured in how users flow through the space.

For the project team, the ultimate measure of success lay in the building’s civic impact. Bennie noted that infrastructure projects of this scale can reshape cities, acting as catalysts for development and social change, while Barrett observed that the engineering effort is largely invisible to users, who experience the building simply as a bright, welcoming public space.