Chair of the Irish Green Building Council (IGBC) and former Dublin City architect, on the ways in which IGBC is reshaping the construction sector’s understanding of sustainability, and the importance of Dublin City Council’s promising social housing development by Grafton Architects.

How is the IGBC effecting a step change in the construction sector’s approach to environmental issues?

The IGBC is working to promote a more sustainable built environment through a holistic approach. When we talk about ‘sustainability’, we look at decarbonisation, resource-efficiency, protecting and enhancing biodiversity in our built environment, improving people’s health and wellbeing, and climate adaptation. By ‘built environment’, we don’t look at building in isolation, we include infrastructure, and neighbourhood.

We go about this mission in four ways.

- Research to develop evidence-based, practical and implementable solutions. Extensive stakeholder engagement – particularly with our membership – is critical in this.

- Advocacy, which is ongoing. We do this in a user-friendly way and try to limit industry jargon. One of example of this is the IGBC’s manifesto produced for Ireland’s 2024 General Election, and which was presented again to the new Minister for Housing. See 3 MEASURES FOR A BETTER, GREENER BUILT ENVIRONMENT – Irish Green Building Council

- Development of tools to support the industry in its transition, for example, Home Performance Index (HPI) Certification. This is a national certification for new homes, similar to certification for commercial development like LEED and BREEAM, except that it’s specifically designed for residential development and aligns to Irish building regulations, EU CEN standards and international WELL certification for communities.

- Training & education for building professionals, which we do through ongoing courses, webinars etc.

What are the biggest misconceptions around sustainability and construction?

This is a big question, but I would say that one key misconception is that it’s all about complex technology and innovation, and that sustainable construction must be expensive. We don’t really have time to reinvent design and construction technologies across the board and a lot of the solutions we need are already there, it’s about scaling them up and joining up dots. The IGBC recently launched an updated Building a Zero Carbon Ireland Roadmap. This argues that the first step towards sustainability and construction is to prioritise projects within Ireland’s National Development Plan (NDP) based on environmental and social needs to 2030. The next step is to maximize use of existing building stock. It’s also possible to reduce construction carbon intensity through a reduction of unnecessary floor areas.

IGBC (2025), Building a Circular Ireland – A Roadmap for a Resource Efficient Circular Built Environment.

What are the biggest obstacles to progress?

The IGBC’s ‘Building a Zero Carbon Ireland Roadmap’ was first launched in 2022. As part of an ongoing process of review and learning, we’ve spoken to stakeholders on how the industry is performing against the original roadmap’s targets, what barriers stand in the way, and what actions should be taken next. The findings are captured in the Building A Zero Carbon Ireland – Industry Insights & Actions report launched a few weeks ago. These include regulatory barriers restricting the use of low carbon construction materials, the investment required to decarbonise including the cost of low carbon materials and lack of effective collaboration around carbon reduction on construction projects. SME’s in particular need support given they make up a large proportion of Ireland’s construction sector. It is even more challenging for smaller organisations to invest the time and money required to measure their carbon emissions, develop decarbonisation plans and take action.

While policy makers and industry are aware of the role of embodied carbon and need to use vacant properties, achieving a balance between demolition and new build and focusing resources on addressing dereliction is a challenge. While there are several reasons for this, a key one – given the critical need to provide homes – is that it is less complicated and faster to deliver more homes in a new-build project.

Industry collaboration can help overcome obstacles. Being open to share best practice and mistakes is crucial (something the IGBC is trying to encourage through its communities of practice). To quote one of our recent speakers, “frankly, we don’t have the time for each of us to learn individually, we need to learn from each other”!

If you could introduce one policy change what would it be?

I sought Marion Jammet’s (IGBC Director of Policy) views on this and I agree with her. Based on IGBC priorities it is to introduce a GWP lifecycle limit value for buildings ahead of the requirements of the Energy Performance in Building’s Directive (EPBD), i.e., on 1st January 2028 (as opposed to 2030). This has already been done in Denmark, France and to some extent the Netherlands. This is critical in reaching our climate targets (14% of our national emissions are linked to embodied carbon in construction), improve resource-efficiency (through less demolition) and drive innovation in construction methods and materials. In turn, it could support sustainable jobs and growth across the country, for example additional jobs in renovation and production of biobased materials.

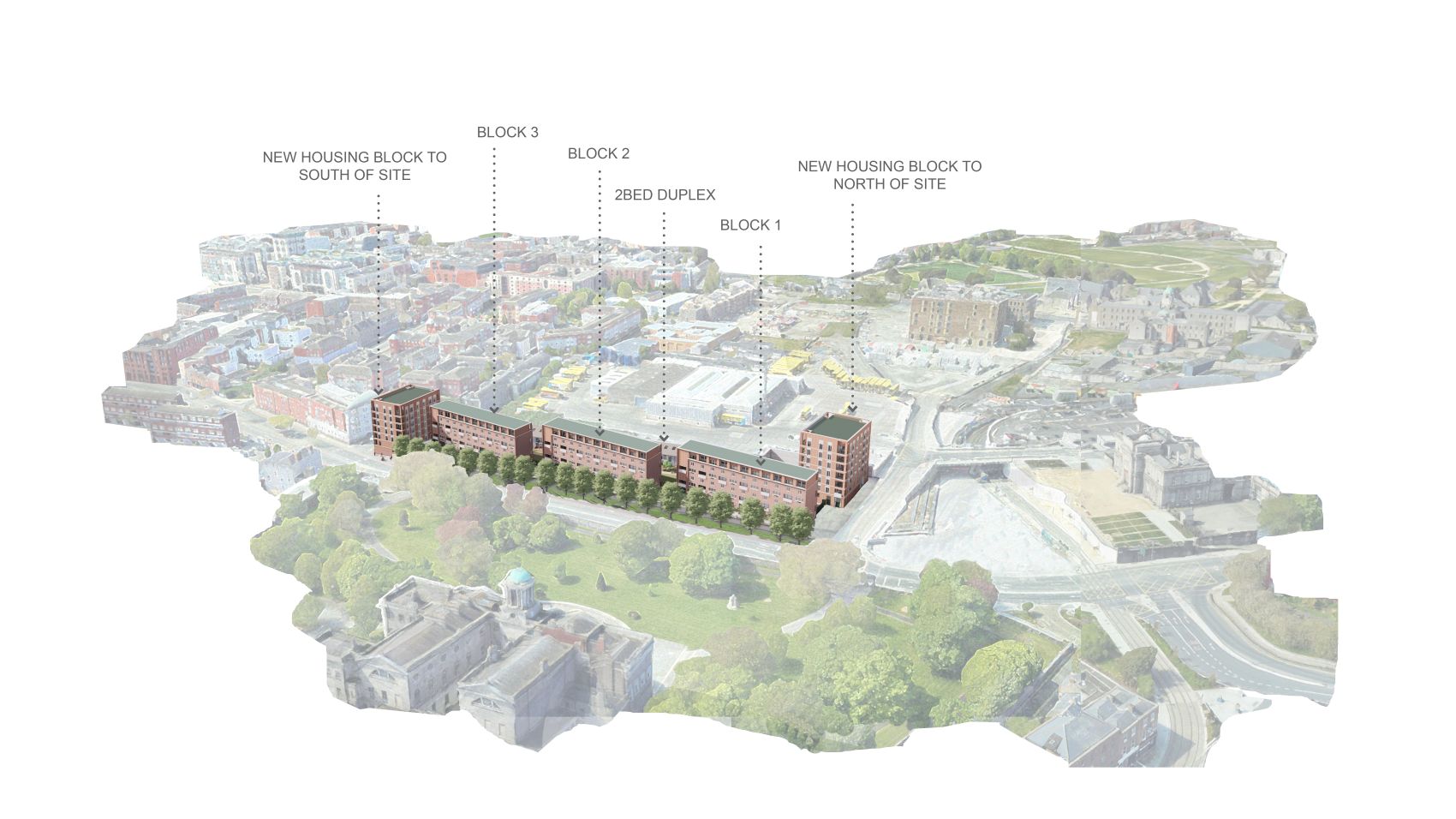

“Constitution Hill public housing project is very important.” Visualisation by Grafton Architect’s of Dublin City Councils latest social housing scheme, Constitution Hill.

Tell us about a project in Ireland that fills you with hope for the future?

I wouldn’t say there’s one project, there are several projects that give me hope.

I’m delighted Dublin Metrolink has been given planning permission by An Coimisiún Pleanála. It’s a huge project but, once complete, it will be a significant move towards reprioritising public transport over private car use in Dublin city.

Dublin City Council’s Constitution Hill public housing project is very important. The project is a retrofit of the three existing 1970’s flat blocks with new buildings filling in the gaps at both ends of the site and along the rear site boundary. The site is prominent, facing architect James Gandon’s iconic King’s Inns, south of the equally iconic Broadstone Station by John Skipton Mulvany, and adjacent to the city entrance to the Grangegorman University Campus. Grafton Architects is the design team leader, the first phase will be complete in 2027. It gives me hope because it will demonstrate that somewhat stigmatised buildings can be elevated architecturally, and through intelligent design, it is possible to reuse existing buildings without compromising performance and quantity.

Proposed view by Grafton Architects of Constitution Hill’s new façade.

Finally, I referenced Cloughjordan Ecovillage in my presentation to Architecture Today’s Dublin City Dialogue event. Cloughjordan is a small town in the Irish midlands, about 150km from Dublin. In 2002, a group purchased a 27H farm close to the town centre to develop a co-housing project based on sustainable principles. The resulting project is remarkable on several levels. It is astonishingly resilient despite significant setbacks. For example, only 55 of the permitted 130 sites have been developed because of town water infrastructure capacity, nevertheless the community persists in seeking ways to resolve this. The project has been a catalyst for wider regeneration. The whole town is thriving with a growing population and unlike many Irish towns, there is very little dereliction and vacancy. The project is a hub for education and outreach on sustainability. It has shared its learnings – successes and failures – with many groups over the last two decades and has arguably been a positive influence on their sustainability efforts. I’m also very hopeful that Dublin City Council’s retrofit project for the Dominic Street Flats will be ground-breaking work. The blocks are vacant as the residents have been rehoused across the street in a new development. This means internal modifications can be kept to a minimum (no need to make the flats bigger to house existing families) and the focus can be on technical experimentation and learning.