Everton FC’s new stadium on the banks of the Mersey at Bramley Moore Dock negotiates fierce winds and heritage sensitivities to deliver a ground that stands comparison with its red neighbours.

It was a bad start. Before a brick had even been laid, Everton FC’s new stadium at Bramley-Moore Dock in Liverpool was causing big problems. Back in 2021, the plans to build the stadium within the Stanley Dock Conservation Area had, along with The Peel Group’s Liverpool Waters development along the River Mersey, been cited by UNESCO as reasoning for Liverpool losing its world heritage status – a major blow for a city so proud of its history.

Then the unthinkable almost happened. Despite plans for a new stadium well underway, the club was almost relegated in 2023, surviving on the last day of the season.

Despite clinging onto the lucrative payouts of the Premier League for dear life, things off the pitch haven’t exactly been improving either. In April this year, the club published its financial accounts, reporting the seventh consecutive year of posting a loss. All in all, the club was £180 million in debt.

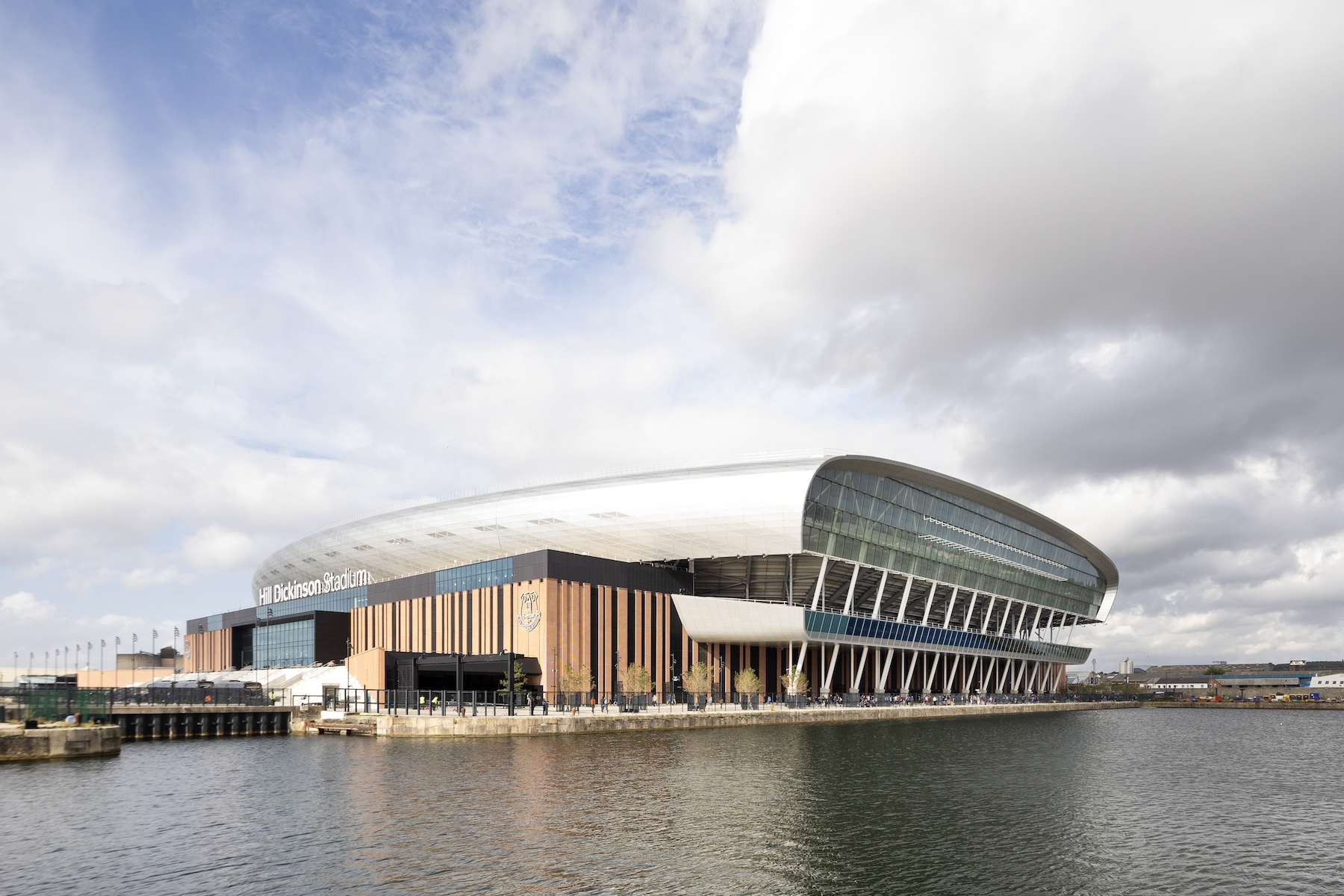

There is, however, a reason to be cheerful – and that comes in the form of its new ground. Officially known as the Hill Dickinson Stadium after said law firm secured a £10 million deal to the stadium’s naming rights, Everton’s new home is an £800 million gamble that its owners hope will help spearhead the club to more favourable fortunes, both footballing and financial.

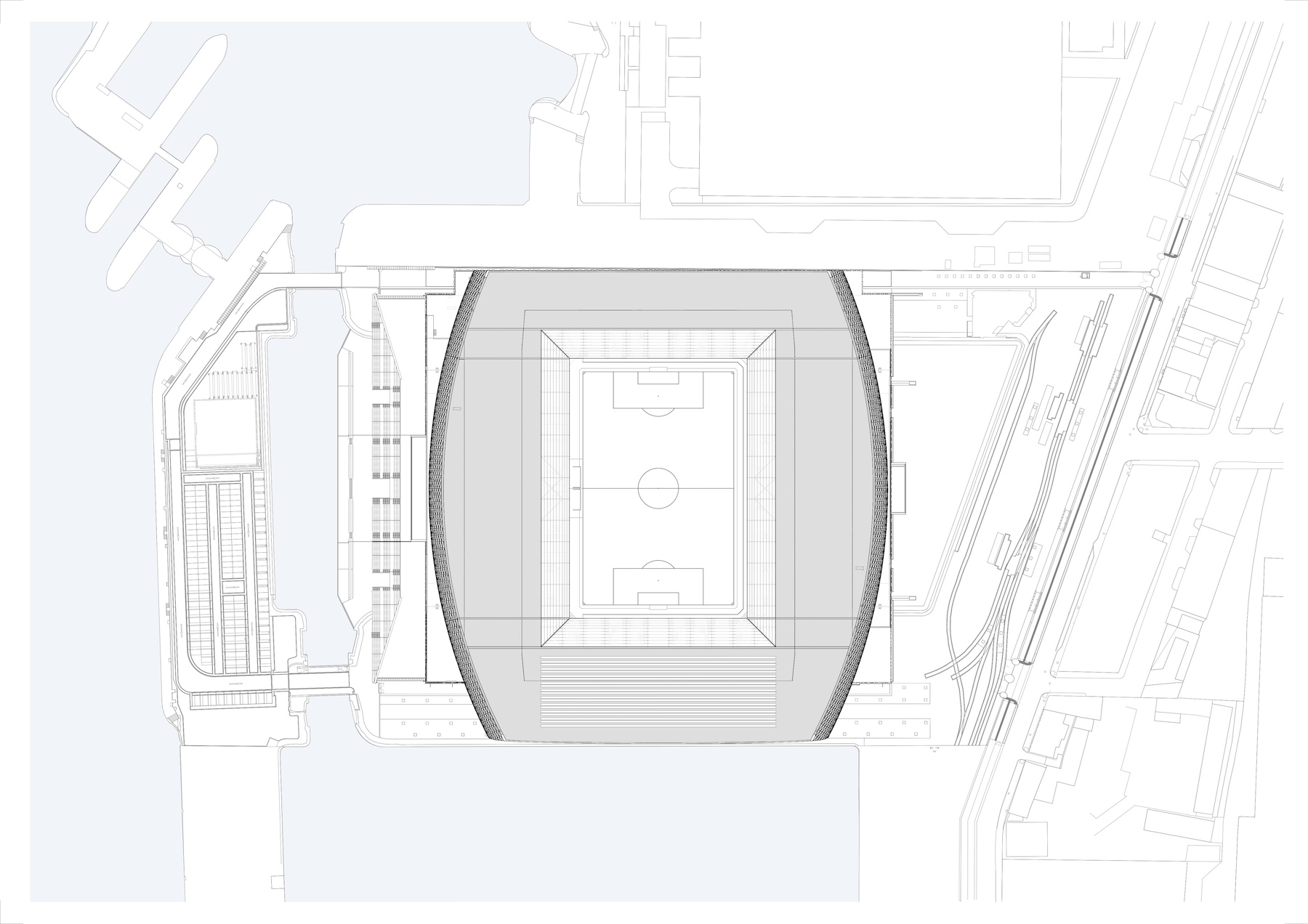

Site plan.

Four years on from the UNESCO ruling, it’s hard to see the damage that’s supposedly been done, at least at Bramley Moore Dock. Yes, some of the actual dock has been infilled, but the trade-off of having a genuinely world-class stadium on the water is worth it.

Talking of which, the project’s concept comes from American architect Dan Meis who was specifically chosen by Everton FC. This was then further developed (from Stage 3 onwards) by BDP Pattern, working alongside contractor Laing O’Rourke.

Meis told AT how the dock’s history and its architecture was the lead influence for thc conept: “The Titanic Hotel, the Tobacco Warehouse, those brick structures. I did a sketch of a brick base with a metal roof, like a wave washing over it — the blue wave of fans across the dock. That sketch pretty much defined the final massing,” he said.

Based in Los Angeles, Meis admitted to being “sceptical” to take the job because, in his words, Everton was a “smaller club.”

But such scepticism was short-lived. Soon Meis was having fans message him about about capacity and materials. “I wake up to new suggestions or questions [from fans],” he said in 2023. Now he even has an 1878 (the year Everton was founded) tattoo on his right wrist.

Fans were asking ‘Why aren’t we building 70,000 seats?’ and ‘Why isn’t that North stand bigger?'”

His relationship with Everton fans is certainly unique. Tom Bowell, an Everton fan is 1988 described Meis as a “legend.”

“He ‘got’ the club early on,” said Bowell. “He was brilliant and really engaging. There were open forum’s on the stadium design that he hosted with club.”

“It wasn’t always positive,” Meis told AT. “There were some really robust conversations about explaining why we were doing certain things. Fans were asking “Why aren’t we building 70,000 seats?” and “Why isn’t that North stand bigger?” All kinds of things. There were lots of debates and I was constantly trying to explain the rationale about how we approach this kind of building and what I believed was the right thing to do for the club. It was quite a journey.”

Capacity was a hot topic. Fans wanted more – certainly, more than their rivals Liverpool (currently 61,276). But Meis was adamant of having something around the 53,000 mark. Better to have a full stadium week-in, week-out, than to have a team playing to empty seats, his argument went.

“He didn’t shy away from having that conversation and fans appreciated that,” added Bowel, who agreed with the decision to have a slightly lower capacity.

Read the full interview with architect Dan Meis here.

“Once Bramley-Moore had been confirmed as the site, that meant there were physical constraints — you couldn’t build 80,000 seats there even if you wanted to,” added Meis. “The principle is to build one fewer seat than you can sell, but that’s always guesswork. I gave the example of Billy Joel selling out Madison Square Garden a hundred times. Should you then build a 200,000-seat arena? It doesn’t work that way.”

“The bigger the building, the higher the cost — not just seats, but concourses, stairways, the whole structure. The most expensive seats to build are at the very top, and they generate the least revenue. So we worked to a number that we believed was right: always full, financially sustainable, and good for atmosphere.”

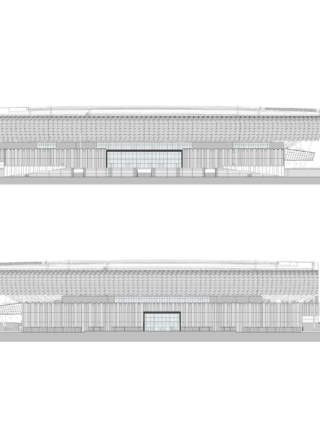

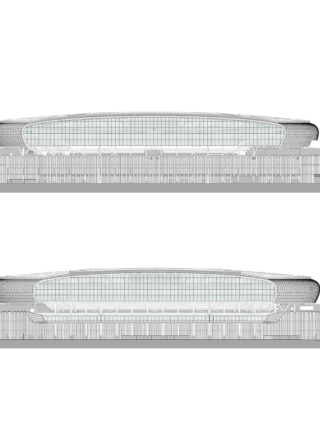

The result, architecturally, is a stadium that defies conventional, typological forms: a brick box, punctuated by vertical black bands, is topped by a perforated, curvaceous silver form. The brick façade is meant to reference the historic (and huge) Tobacco Warehouse found due south in Stanley Dock – a bold attempt and one that will look better with age – while the roof structure is unashamedly modern.

From afar and close-up, this material juxtaposition is a pleasing one. It’s expected that many fans will arrive on foot, taking the one-mile walk from the Sandhills Merseyrail station – which is pencilled for an upgrade. From this route, the stadium gradually begins to dominate the view, particularly when looking down from Blackstone Street when it fills the road – quite a sight.

The route also highlights how this is very much an industrial area. You will walk past shipping and trucking businesses, steel and timber merchants; Everton’s new neighbour is the United Utilities water treatment plant – a building that’s all pipe and no windows. This is by no means a bad thing. If anything, it adds a bit of edge.

This context is also important as the stadium bills itself as a regeneration project, set to “contribute £1 billion to the local economy and create 15,000 jobs.” Such claims are often spurious, and Everton should be wary of how a similar plan adopted by Southampton FC at the turn of the Millennium: the club’s stadium was meant to regenerate its dockland site but has fallen well short of making the impact it wanted to make. Indeed, rejuvenated regeneration plans are underway.

On Merseyside, though, there are already hints, glimmers, that change is afoot with a couple of Everton-themed businesses now inhabiting some of the once dilapidated structures on Regent Road which looks onto the stadium.

Running north to south, this long road is also lined on the stadium side by the old dockland site wall. A listed structure with turreted gatehouses and made from granite-rubble, it’s tall enough to hide the stadium once you’re by it, forming a convenient barrier to the stadium site – a historic membrane if you will. Holes punched through to create fan gates which, once through, reveal the stadium in all its glory.

Left and right: the dockland wall that traces the eastern edge of the stadium site. (Credit: Jason Sayer)

Here there is more history on display: a Grade II-listed Hydraulic Engine House dating back to 1883 sits alone in the expanse between dockland wall and stadium, standing on the original cobblestones and among the original railway lines and mooring posts – remnants of the dock’s previous life. A use for the (now) folly is yet to be decided on.

This attempt to be rooted in place is a successful one. Evertonians were traditionally dock workers, after all. “In a way it’s like they’re coming home,” said Jon-Scott Kohli, architect director at BDP Pattern. “Providing that kind of connection feels really meaningful.”

This is a contrast to what came before as well: Everton’s former home, Goodison Park, had been the club’s home for 133 years and was at the heart of a community, surrounded on three sides by rows of residential streets – walls of blue from the (rather drab) stadium façade filling the views of many. Now, the Hill Dicksinon Stadium is at the heart of something different.

Let’s not also forget how, as a typology, the stadium is one that seldom embraces its site. Often, modern stadia are hermetically sealed environments that aim to keep the experience of being a fan in. Everton is more porous. There are windows in – very big windows in fact and you can see it from the river. Sure, the dock wall boundary lays down a hard marker between stadium site and general vicinity but the stadium hardly feels closed off.

Goodison Park. (Credit: Arne Müseler via Wikimedia Commons)

With industry and history on one side, there is the River Mersey on the other. The two almost perpendicular site boundaries of dockland wall and fierce river make this an exciting place to be. Contrary to UNESCO’s ruling, the stadium’s location is in fact a thrilling one.

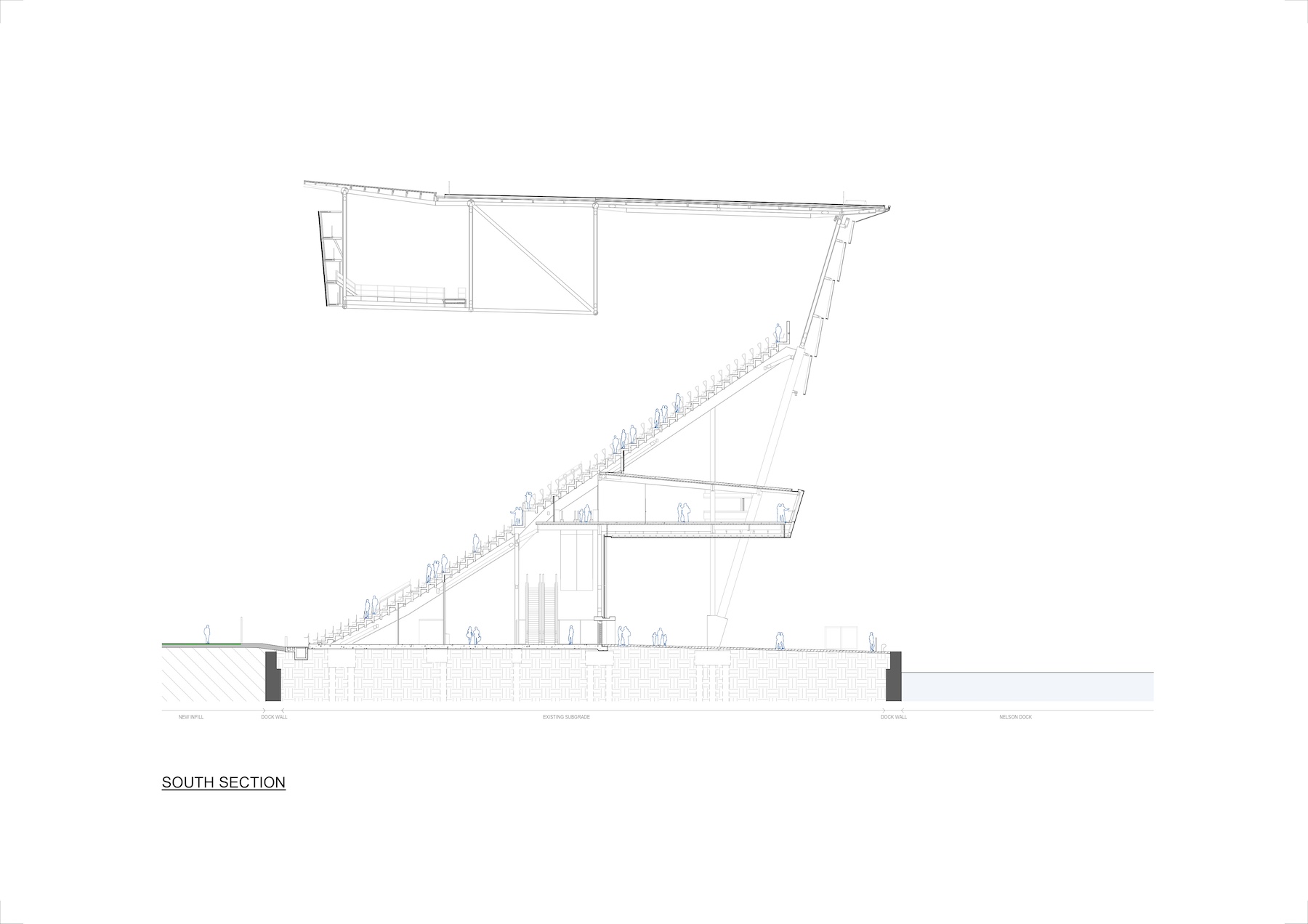

Almost too thrilling, in fact. Such is the voracity of the wind that comes off the Mersey that several measures have had to be put in place to mitigate wind from the western and southerly locations of the site. Perforated steel baffles have been employed to do the job, directing and dissipating the wind. If too extreme, gates can be closed to close off dangerously windy areas.

On a calm day though, the external western terrace is a very pleasant place to be. This edge between river and stadium steps down to offer seating, creating an ideal spot to have a pint before the game. Further west is Wallasey, to the south is the city of Liverpool with the Three Graces spied in the distance, and looking northwards one can see where serious industry has migrated to, now occupying the Gladstone Dock, with the Irish Sea beyond this.

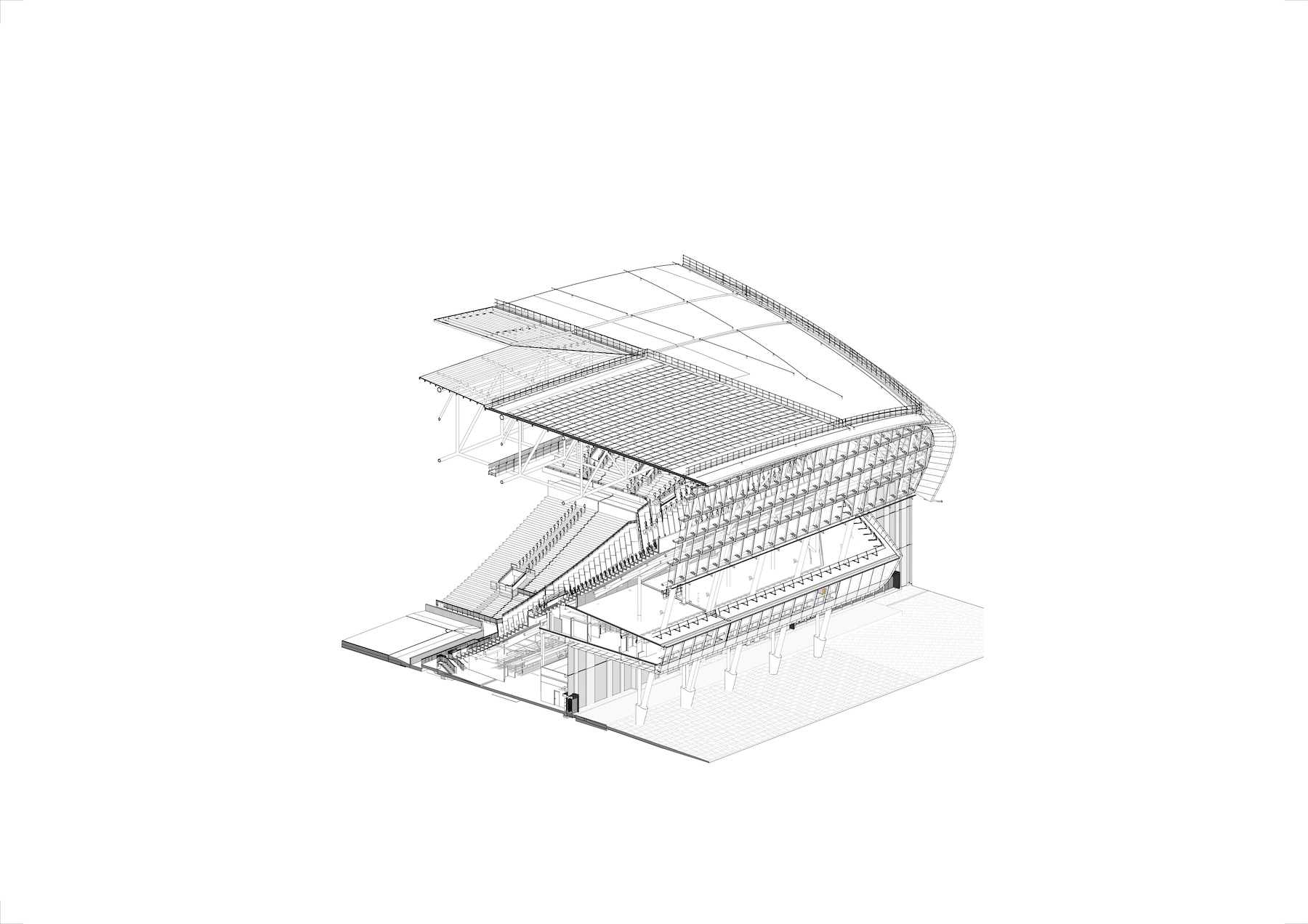

Stepping into the stadium itself enters one into wide concourses beneath the seats. Pleasingly, views of the brilliantly green pitch can be seen immediately – a nice reminder of why we’re here. Anyone who’s been to a stadium before will be familiar with the no-nonsense vernacular commonly employed for such spaces which can be cramped, busy, sometimes raucous areas. But at Everton these are generous spaces that offer room to breathe.

On the south side, the views from the concourse down toward the city may be some of the best of their kind in the country, courtesy of angled glazing that protrudes out as close to the adjacent Nelson Dock as it can. This glazing is emulated on northern side up until the seating, letting light onto the pitch and providing visual balance.

And so to the business-end of the stadium: the pitch-side seating – something which BDP Pattern has taken meticulous care over.

The new stadium offers a capacity of 52,888, up from the 39,572 at Goodison Park – with a long waiting list for season tickets, most additional seats have now been absorbed. The new stands are steep, as steep as regulations permit (35 degrees), with the steepest sections, dauntingly, being at the top, around 35 metres above the pitch. (The building overall is just under 45 metres high – a deliberate choice, for being above 45 metres would have triggered a different planning classification).

There is sound logic behind this approach, too, being driven primarily by a desire to fit as many seats in as possible and to ensure each seat has a good view. With regard to the former, the architects learnt, wisely, how important proximity to the pitch is for atmosphere and fan satisfaction, eschewing the elliptical bowl formations employed in some modern stadia, West Ham’s Olympic Stadium being the worst offender, something picked up on by Meis.

“West Ham’s move was tragic: leaving a historic ground for something soulless, with poor sightlines. Even Arsenal’s Emirates, hailed as state-of-the-art, doesn’t have fans right on top of the pitch.”

Ensuring a decent view, however, involved employing some rigorous calculations, namely the ‘C-Value’ – a mathematical practice and common parlance among stadium designers that helps determine the optimum seat location based on how much they can see ahead of them.

To aid this, thick reinforced glass balustrades, typically concrete elsewhere, can be found in the stands to minimise view disruption.

“We used a bespoke parametric script that defines the geometry of the roof, the steelwork, and the bowl, and tests every seat by drawing sightlines to all four corners of the pitch,” explained Kohli.

Kohli and his team also produced a movement diagram that mapped out what spectators naturally do in their seats. “They shift slightly,” he said. “On some projects we’ve been forced to assume people sit rigidly, facing forward. Then even a tiny obstruction is classed as a defective seat. That’s unrealistic. Our approach accepts natural movement: a small adjustment is comfortable, but if you need to crane your neck it becomes a restricted view. That influenced the use of glazed elements here, ensuring people can see through.”

At Goodison Park about half the seats had restricted views because of columns. With the new stadium, every seat has a good view, apart from a handful next to the press desk, which are sold appropriately.

“What people regard as a ‘good view’ is subjective anyway” added Kohli. “Some want to be in the home stand, close to the action; others prefer a broader perspective. We’ve designed to cater for all.”

While not elliptical in form, the stadium seats still fill a bowl – of sorts. ‘Stands’ however, remain defined – a smart move as football is, for better or worse, inherently tribal. At some clubs, fans even chant about what section or block of the stadium they’re in. Here, Everton is hoping to create a “wall of blue” that echoes the Liverpool’s Kop end and Dortmund’s Südtribüne ‘yellow wall’ – famously single-tiered stands known for generating atmosphere.

As for the actual business-side of things, another key change in stadium design is seating types.

“It used to be general admission, a directors’ box, maybe one lounge. Now there’s a wide spectrum of hospitality and premium offers,” said Kohli. “Different fans want different experiences – some to be in the crowd, some focused solely on football, others here for business or socialising. We’ve designed spaces to cover all of that.”

In total there are nine tiers of hospitality. The ‘Moore Lounge’ is among the highest and allows guests to sit next to the directors, with a match-day goers getting a seven-course meal and access to a wine-tasting room. Other tiers, meanwhile, afford fans to view players coming out from the dressing room and onto the pitch behind one-way glass.

Perhaps more importantly, there are 279 wheelchair positions inside the new stadium, as well as sensory rooms, faith spaces, and gender-neutral toilets, making Everton one of the most accessible clubs in the country.

Everton’s new owners, The Friedkin Group, will hope such efforts pay off – both literally and in a footballing sense. Recent high-profile movers Arsenal, Tottenham and West Ham will attest to the difficulties in moving stadium, particularly with atmosphere and results on the pitch.

As for the UNESCO ruling, officials could well do with revisiting the Bramley Moore Dock. Far from damaging the “outstanding universal value of the site” Everton’s stadium is a more suitable inhabitant – and one that, if anything, enhances the historic dockland site.

According to Bowell, the club – and its previous owners – had been looking for a new stadium for decades. Sites such as Kirkby drew ire among fans for being too far out. “There were a lot of false dawns,” said Bowell. “I never thought I’d see it happen in my lifetime.”

On first impressions, the wait looks to be worth it – for the Hill Dickinson Stadium already feels like a genuine home. In their first game at the new ground Everton Hosted Brighton, a game pundits had tipped the home team to lose. Worries about atmosphere were promptly dashed, as were those on results, as Everton won 2-0: as good a start as any to a new life on the river.

Credits

Client

Everton Football Club

Architects

Meis Architects (stages 1–3), BDP Pattern (design development and delivery)

Client design guardian

Dan Meis

Main contractor

Laing O’Rourke

Engineers and all building performance disciplines

Buro Happold

Landscape and public realm design

Planit-IE