For more than two decades, London based practice Chance de Silva has pursued the question of what happens when art and architecture evolve simultaneously. With a design method shaped through collaboration with musicians, performance artists, painters and filmmakers, their recently completed project continues this enquiry, but this time, the collaborator is the city itself.

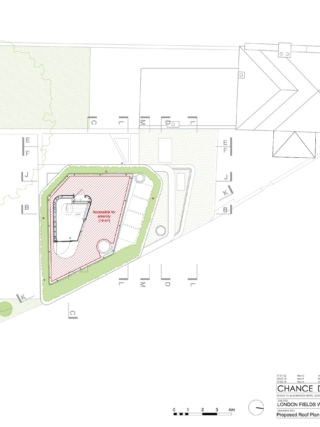

Stephen Chance and Wendy de Silva have always gravitated towards unlikely sites; slivers of residential streets and awkward odd corners developers fear. For Chance, constraint isn’t something to overcome but a vital prompt for collaboration. The site of the practice’s latest project – named London Fields West (LFW) in homage to John Coltrane’s Central Park West – was originally home to a series of small cottages, which evolved into a Post Office in 1873, before becoming a Mission Hall in 1896. The site was acquired via auction after the hall had been demolished, leaving four out-of-use, derelict car garages.

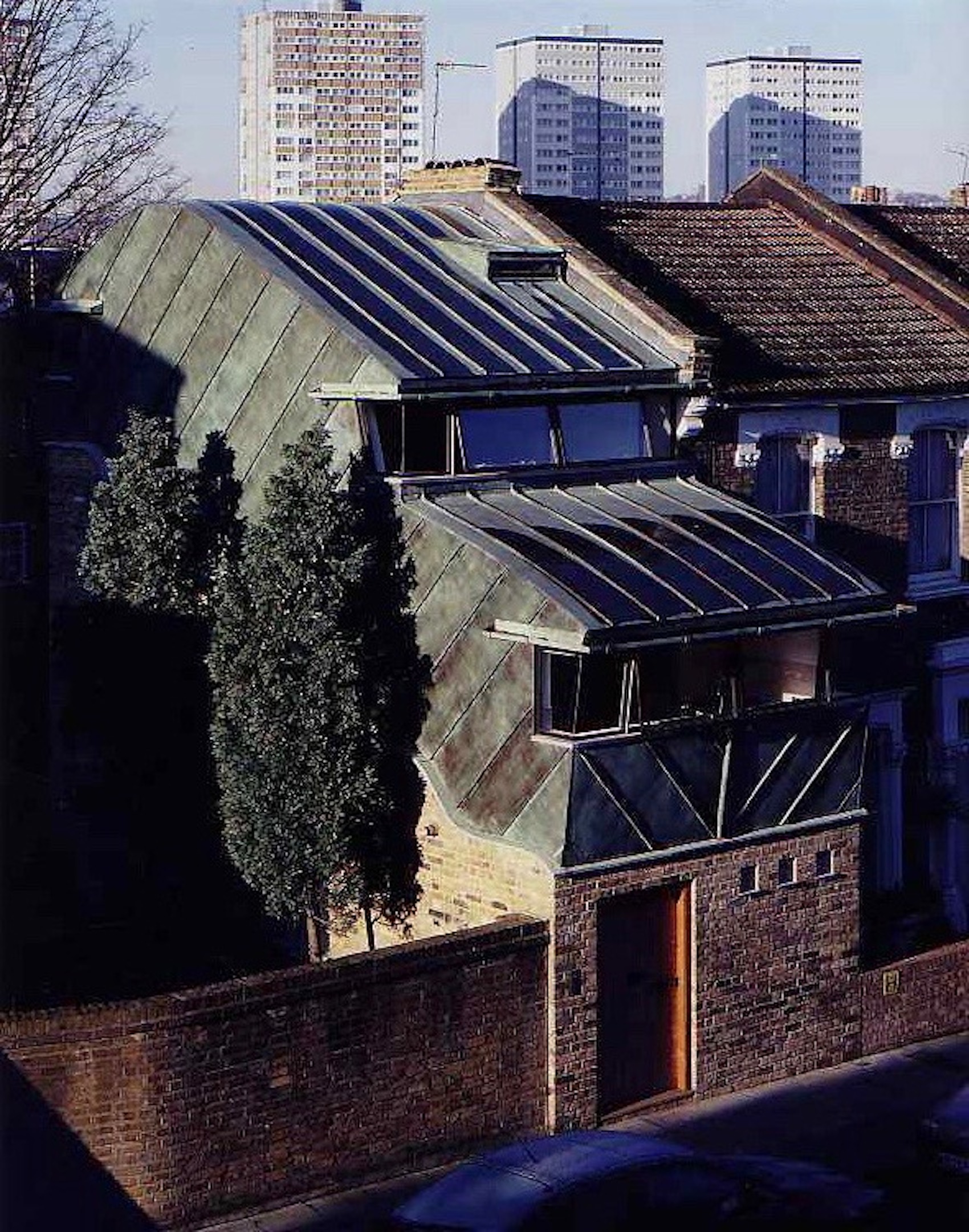

Views south, down Greenwood Road (left) and of the rear of the property (right), emphasises the collaged urban setting in which London Fields West sits.

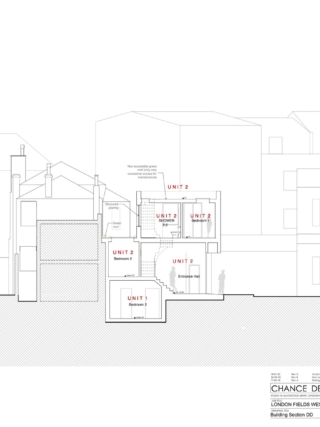

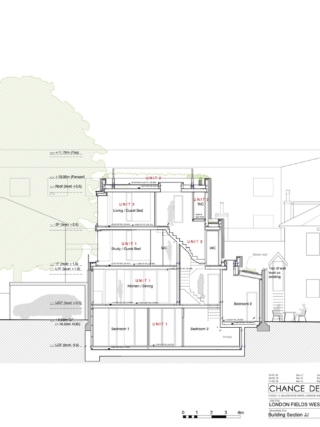

LFW sits at a crossroads in more ways than one. To the east and west of the site are a combination of two- to four-storey Victorian and Georgian terraced houses, to the north is a four-storey, red brick housing association building, while to the south is Morland Estate’s 12-storey, 1960s tower block. South-east of the site sits London Fields, with the lido running parallel to the shared road. Post-war council housing, terraces with the occasional shopfront, and an inner-city park meet at this wonted urban collision, and the addition of LFW works hard to tie the challenging classic and contemporary contexts together.

Tactful stepping of the building navigates intricate vantage points, with the tower to the south, partially obstructing views of the park, and private gardens to the north and west. Thoughtful massing stacks the two interlocking units which weave between one another to maintain park views: Unit 1 has an enclosed courtyard to the western boundary at lower ground level, which is overlooked by a small terrace and onto which the two bedrooms open up. Unit 2 has a large roof terrace.

Both units have south-facing balconies with views over the park, and living rooms with natural light entering from three sides. The surrounding landscape is framed by folded corner windows, that pull selected views into focus; a slice of the tower block, or strip of trees. Cast concrete is left raw, but when combined with warm colours such as the ochre used in Unit 1 – made by artist Onya McCausland from Teesside river sediment – and wooden floors, feels comfortably enclosed, like a hollow carved out from the site itself and wider city beyond.

The initial plans were for the upper levels of the façade to be clad in vertical timber fins treated in a range of colours by the painter Barbara Nicholls, however this was swiftly vetoed due to cladding scepticism that arose amongst insurers in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire. Chance de Silva were forced to change tack last minute, opting for a red zinc cladding with vertical standing seams.

While it is hard not to mourn the quirky, billboard-esque vision, the final palette cleverly landmarks the quiet street corner, with soft zinc rising above a light brick base, and a timber lantern atop. The building’s elevations patch together to reflect the diverse building stock that meets at these crossroads much as a disco ball simultaneously camouflages and twinkles.

Despite Nicholls’ work not making the final cut, Chance de Silva maintain that LFW is a collaborative work. Working alongside artists and musicians on previous projects has undoubtedly influenced the practice’s process, and uniting their work is this commitment to moving architecture beyond its conventional strictures. When comparing architecture to filmmaking, Chance defines the discipline as one that is inherently collaborative, financially risky, technically complex, yet still capable of producing works of art. Their early project, Venus, set this tone, whilst the later project, Vex, expanded on the idea.

Across these collaborations, a pattern emerges: each project is in conversation with its context, whether physical, historical, musical or industrial. LFW draws out this method further, carrying forward techniques and considerations accumulated from decades of cross-disciplinary exchange: the sound of construction, the sediment of watercolour, the rust of steel and the movement of bodies through space. For Chance de Silva, these elements aren’t embellishments but part of the structure of architecture itself: unpredictable, layered and alive to the possibility that a building can be more than a building.

Left: Venus in Highbury (credit Paul Tyagi). Right: Vex in Stoke Newington (credit Hélène Binet).

Stephen Chance, director at Chance de Silva alongside Wendy de Silva, sat down with AT to discuss how the project evolved.

You seem to have a knack for spotting unusual sites. What’s the method?

I’m good at seeing a site’s potential. Sometimes you find out who owns it, write a letter, and often, nothing happens. But with councils it’s a bit different. You have to be persistent, keep pushing, almost embarrassing them into action. When land sits empty for years during a housing crisis, you wonder why it isn’t being made available to architects or small-scale developers who’d relish tricky sites.

What is it about these ‘tricky’ sites that attract you?

They’re fascinating. Developers avoid them because of the complexity; but for architects, complexity is an opportunity. That’s especially true for us, because collaboration is central to our work. We came out of the 80s in London, living in squats with artists, and that spirit has stayed with us.

How did the collaboration start?

One of our first collaborations involved the artist Matt Hale at Venus. Hale embedded conceptual works into the house: a glass covered manhole and a take on the ‘stained glass window’ filling tall glass cylinders with household chemicals. These pieces were developed simultaneously to the building’s design, with artist and architect working alongside each other. When you’re your own client, you have the freedom to create a building in a similar way to how artists create a body of work.

How early in the project do collaborators become involved?

Ideally at the start, so the artwork grows with the architecture. Matt was great at this as he could think conceptually during the early design stages. Others prefer to see the finished building before deciding, but each brings their own process. Artists work through intuition, history, personal stories; architects do too, but we’re trained to justify everything. Artists, however, remind you that subjectivity matters.

With Vex we chose to set an external reference point: Erik Satie’s Vexations, a repetitive 18-hour piano piece. Scanner (musician Robin Rimbaud) composed the sound and Chance de Silva designed the house, both influenced by the Satie piece. It’s how John Cage and Merce Cunningham worked – separate processes that are later merged.

So it’s important the ‘constraints’ vary by project?

Exactly. Venus began with the physical site; Vex began with a piece of music. Each collaboration establishes a different set of constraints to work within. And artists often appreciate the challenge of overcoming limitations just as architects do.

Do these collaborations affect the architecture itself, or simply add layers alongside it?

They influence our thinking. Maybe not always the building at hand, but certainly the next one. A colour, a material, a story – it filters through. The ochre wall in LFW came from an artist’s pigment reflecting the iron-rich rivers of the north-east, in the landscape that inspired our corten house Cargo Fleet. You carry these influences forward. Some architects think that’s pretentious, or they insist architecture isn’t art. I don’t care about those distinctions. I think films are a good analogy for art/architecture collaborations: large numbers of participants, financial constraints, conflicting personalities quite often, yet still the potential for art.

Do past collaborations shape your approach to projects where no artist is involved?

They widen the field of possibility. Even if an artist isn’t physically present, the mindset remains: What if? What could this site become? Who might inhabit it imaginatively? It keeps the architecture open, responsive.

Could this collaborative method scale to larger or affordable housing?

Absolutely. I’ve done social housing and regeneration work. Those processes involve community workshops, exhibitions, participatory events – that’s collaboration. Artists can contribute to those contexts. The idea that the ‘art’ part is indulgent is misguided; unlocking the creativity of the participants is valuable.