Jihoon Baek discusses his design thinking and approach for his winning entry to the 2025 AT Awards Student Prize, ‘Riddle, Rubble and Ripple’.

My proposal tackles public open lands for leisure and sports that are too often temporary or limited in scale, conditions that erode long-term social, environmental, and functional resilience. Focusing on Metropolitan Open Land, with its ageing leisure infrastructure and constrained, controlled river, I propose a revitalisation strategy that delivers equitable, water-based leisure infrastructure. This strategy responds to climate urgency, especially flood risk, while enhancing environmental performance, public accessibility, and community value, in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

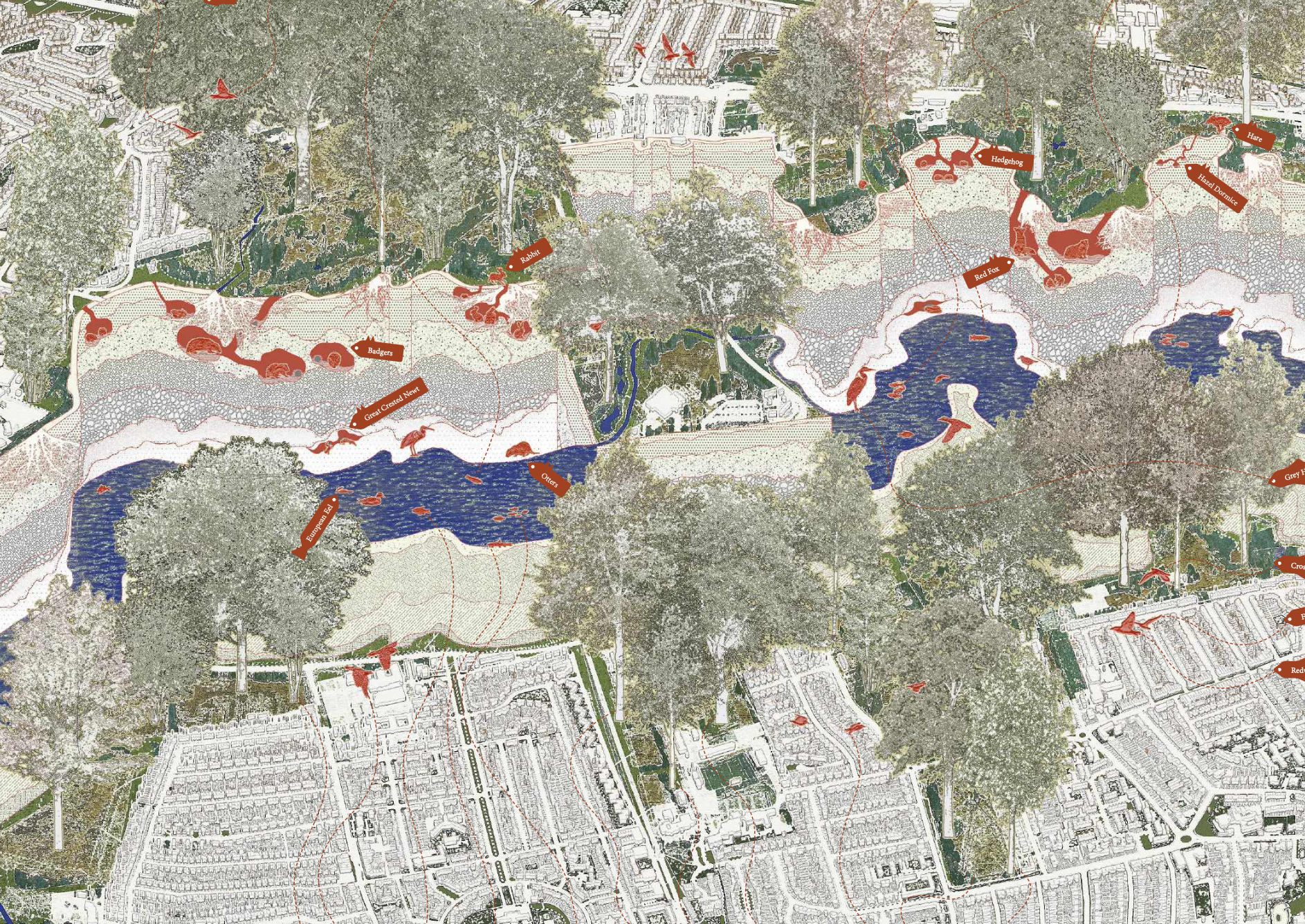

Metropolitan Open Land (MOL) is a planning designation unique to London. Like the Green Belt, it protects green space to safeguard public access to leisure areas and to resist intrusive development. The project site lies within the MOL floodplain at Gurnell Leisure Centre in Ealing, bordered by the River Brent and neighbouring towns. Although the MOL covers about 10,000 hectares, nearly half is effectively inaccessible, often occupied by private golf courses and further fragmented by river infrastructure that disrupts natural floodplains. The Gurnell Leisure Centre itself, only fifty years old, is scheduled for demolition well before the end of its material life, illustrating the fragility and short-lived nature of public leisure infrastructure.

The word leisure comes from the Latin licere, meaning ‘to be allowed.’ Yet, across the Metropolitan Open Land, access is far from universal. Instead of welcoming everyone, the land often fragments towns, disrupts functioning floodplains, and weakens living ecologies. This project reimagines the existing leisure centre and its surrounding infrastructural barriers as opportunities to transform disconnection into connection, restoring accessibility and creating truly equitable leisure across the MOL while strengthening the land’s resilience for active public life.

Reconnecting through existing infrastructure also draws on the local memories shaped by recurring floods. Like the short-lived leisure and river structures across the Metropolitan Open Land, residents’ lived experiences have long been governed by distant authorities and mechanical flood controls. These interventions have left the floodplains less resilient to rising flood risks. Over time, the project recognises that recovering the local memory embedded in these floodplains is essential to achieving truly equitable leisure.

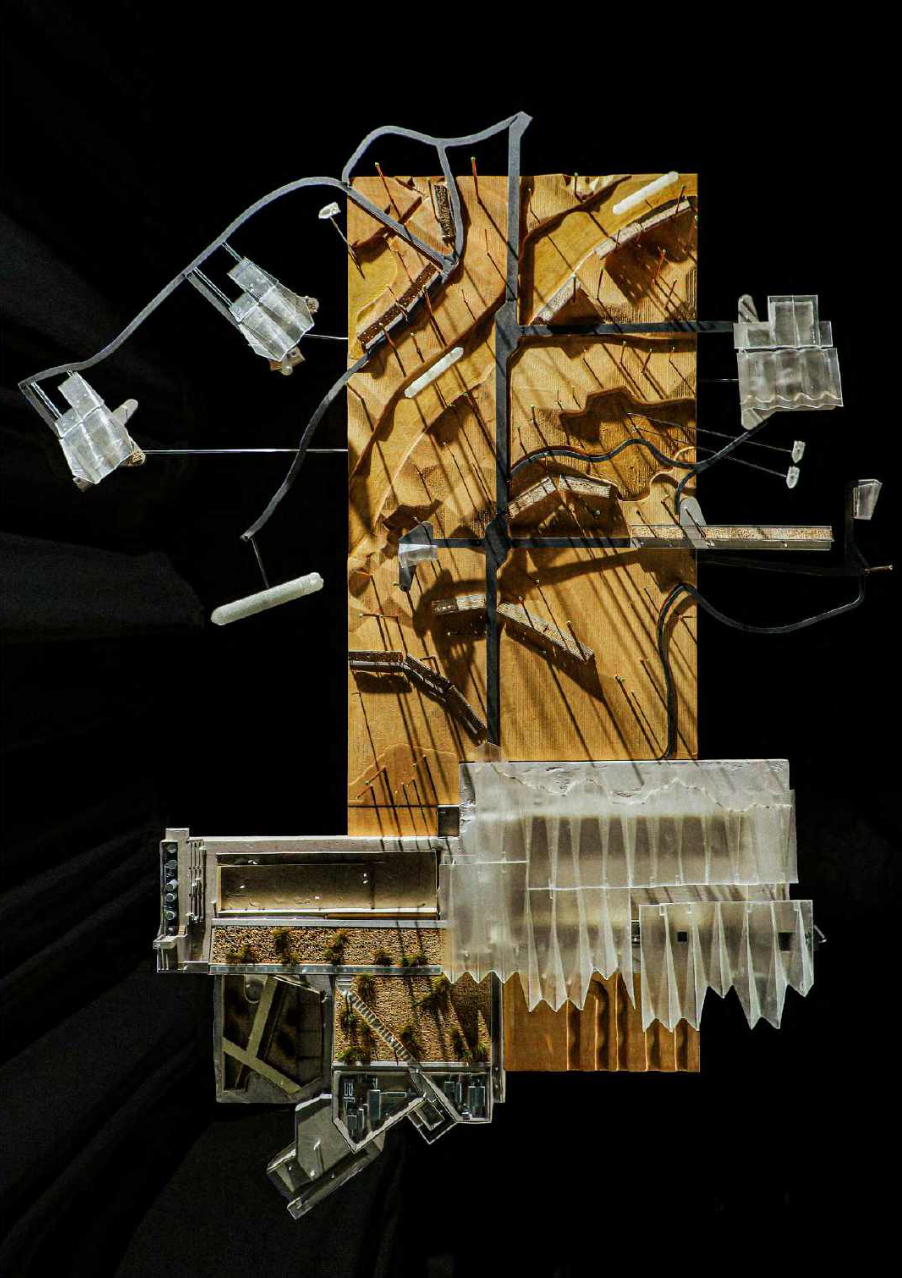

This process led to a series of sketch models exploring how existing infrastructure could be repurposed to revive local memories of intimate leisure along the River Brent and across the floodplains of the Metropolitan Open Land. The design also draws historical inspiration from the former wastewater treatment facility on the site. Elements are reimagined: a corrugated roof becomes a bird hide, brickwork transforms into public baths, and concrete slabs evolve into branching water channels that enrich natural flows and reconnect river-driven ecologies.

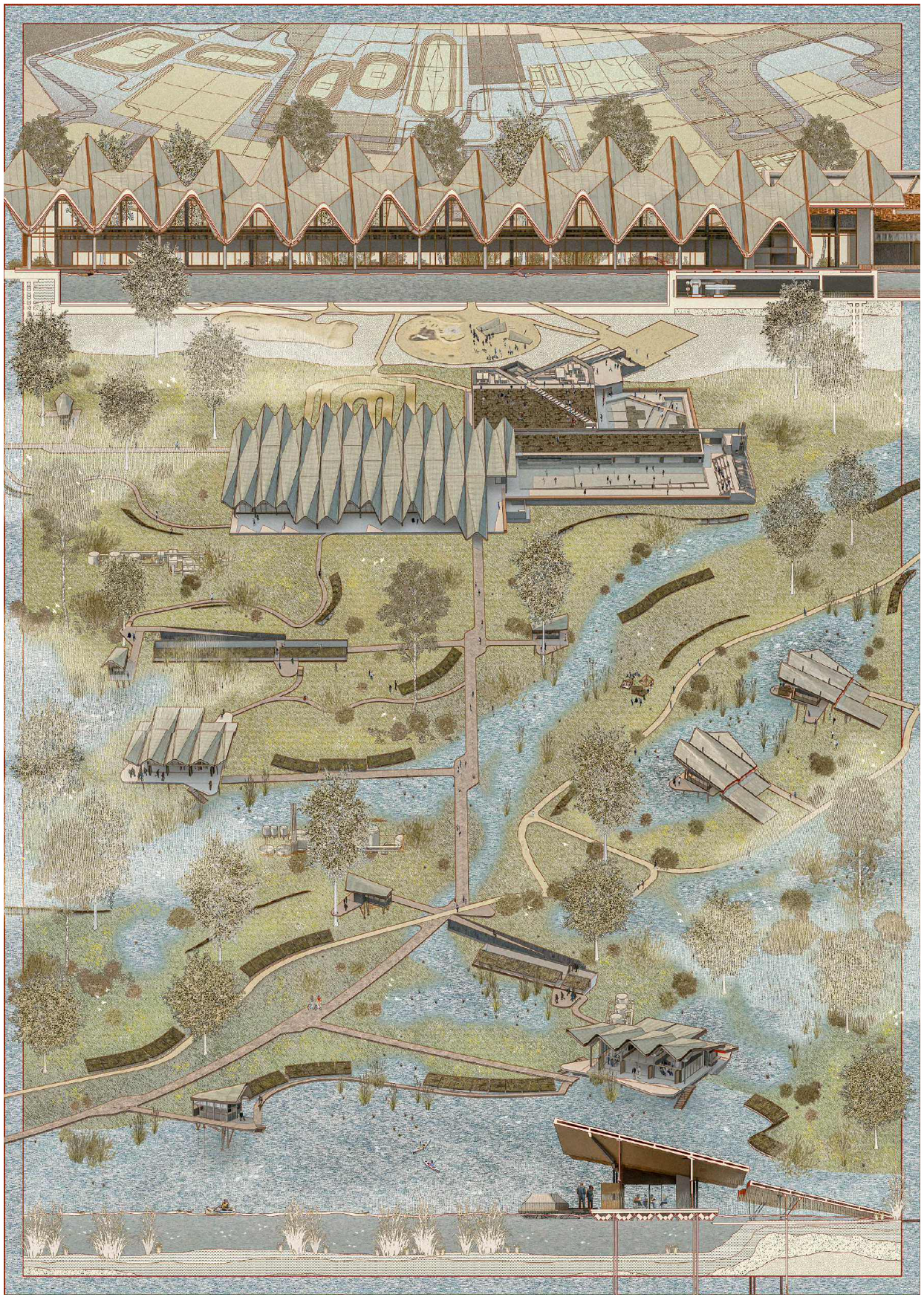

The site plan strengthens the existing ecology and landscape by introducing new tree planting. Flood-risk zones are carefully mapped, and trees are planted in three distinct layers that respond to both fluvial and surface flooding. A new footbridge reconnects towns once separated by the river, linking the retrofitted leisure centre with newly introduced community hubs and small respite huts.

A central argument of the proposal is to retrofit the existing building rather than demolish it. This strategy can access Low-Carbon Retrofit Grants and ease the council’s capital burden. Based on the costing exercise, retaining the substructure and most primary walls keeps the full retrofit cost to about £18 million, an estimated £1 million less than demolition and new construction. Beyond financial savings, the approach promotes long-term land stewardship by extending the RIBA Plan of Work beyond end-of-life and advocating enduring partnerships specifically for MOL. The project engages architects, the Brent River & Canal Society, residents’ associations, local colleges, and makers to deliver community-based flood-resilience education and workshops.

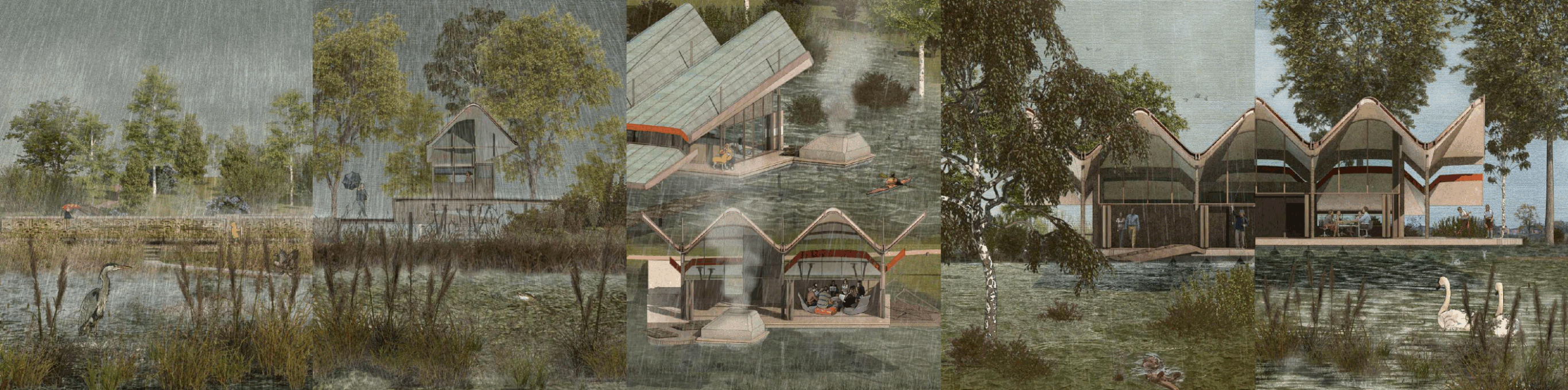

The clusters of floodplain leisure infrastructure are comprised of: the leisure centre, that blurs the threshold between indoor and outdoor water-based sport and recreation; community hubs that teach flood defence for the wider Metropolitan Open Land; and open-air hubs for moments of solitary connection to floodplain ecology or for socialising with one another. Holistically, they provide an environment that rehabilitates the local memory of living along floodplains and nurtures resilience through enhanced ecological and social connections.

The in-building water-sport and leisure programmes, together with their supporting facilities, are repositioned to optimise passive humidity control and enhance thermal comfort, allowing moderate indirect sunlight in the interior without glare and ensuring natural ventilation. Retaining the existing substructure reduced structural requirements for the eastern swimming-pool extension, which is built with biosolid-mix concrete. The building’s geometry adopts a gentle slope, clad in biosolid-mix terracotta panels and refitted standing-seam steel sheets, creating a continuation of the landscape rather than an obstruction. The chosen materials and spatial layout provide clear circulation and robust fire resistance, supporting long-term wellbeing and safety within the building. The structural design embodies resilience through adaptability, using three beam lengths joined by rotating pin connections in line with design-for-disassembly principles. This approach enables the structure to adjust and evolve to meet both ecological and changing community needs, rather than resisting them.

In the first of three narrative sequences, the project demonstrates the retrofit of the existing Gurnell Leisure Centre by repurposing building fragments and refitting systems with modular components. On-site treated biosolids in the process of purifying the contaminated soil and river water are used in concrete and terracotta mixes, while salvaged steel panels form the roofing. The design creates open outdoor leisure areas, showcases visible sustainable energy systems, and provides an accessible roof that extends the natural landscape into the building.

A folded-plate roof provides structural integrity with minimal internal columns, maximising openness while introducing geometric patterns that make the roof appear cradled by the surrounding tree canopies. Bush-hammered finishes on the roof interior and column exteriors integrate the building’s design intent with the growing trees around the perimeter. The roof’s rippling form is echoed across smaller structures throughout the site, creating programmatic coherence and supporting nature-driven, integrated uses across the Metropolitan Open Land.

Guided by the design intent for adaptability, the building is envisioned to respond to rising and receding water levels during floods, allowing both humans and non-humans to sense environmental change without reliance on mechanical systems. This is demonstrated in the community hub, where the rear is anchored to the ground while the front floats on a meshed foundation filled with recycled plastics and stabilised by poles. These hubs also function as workshops for producing biosolid-mix terracotta panels, used both to roof the retrofitted leisure centre and as freestanding installations on site. The panels create discreet spaces for observing floodplain ecology as wildlife hides and, over time, form low mounds as sediments naturally accumulate behind them. This creates a lasting moment, as the soil accumulating behind the standing panels provides refuge for endangered local fauna and gradually shapes a new landscape. Human interaction remains indirect and non-destructive, enhancing the flood-attenuation capacity of the Metropolitan Open Land and strengthening the symbiotic relationship between people and wildlife.

The building’s energy and heating systems operate with minimal reliance on the central grid. Heating is supplied by a river-water source heat pump and supplemented by waste heat recovered from the pools. An integrated micro-anaerobic digester generates additional bioenergy to power the system and produces biosolids that can be reused as sustainable building materials.

To summarise, the project extends beyond retrofitting a deteriorating, short-lived leisure facility to rethinking the Metropolitan Open Land itself, an area challenged by rising urban flood risk, a shortage of equitable social and active leisure space, and the need for enduring public infrastructure. The design introduces a flexible structural system that responds to the land with resilience, water-flow-driven leisure programmes and practices that honour local memories of flooding, and ecological stewardship that establishes responsible reciprocity between people and other organisms. Together, these strategies aim to secure a long-term, sustainable future and safeguard public access to vulnerable open floodplains on the Metropolitan Open Land and beyond.

Jihoon Baek’s project was the winner of the AT Awards Student Prize. Take a look at the winners in every category here.