A new library is the first move in alma-nac’s reworking of the Junior and Lower School campus at London’s Dulwich College. Former pupil Ken Okonkwo explains how the project embeds net zero principles, reflects the school’s culture of curiosity and collaboration, and has doubled the number of borrowed library books.

Dulwich College is an independent boys school in south London. Founded in 1619, famous alumni include polarising MP Nigel Farage, the renowned explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, Hollywood actor Chiwetel Ejiofor, and the novelist and screen writer Raymond Chandler, after whom its newest building is named. The school is open to both day pupils and boarders who attend the Junior School from ages 2-10, the Lower School from 11-13 (11+), Middle School (13+) and finally the Upper School (sixth form) from 16-18.

Set within the Dulwich Village Conservation Area, the most recognisable parts of the school are the impressive red-brick Grade II* listed main buildings, designed by Charles Barry Junior. Completed in 1869, the three blocks are joined by single-storey cloisters in the Northern Italian Renaissance style with cream terracotta string coursing, and are without doubt the jewel in the crown of the vast campus.

Aerial view of the Raymond Chandler Library within the context of the wider campus.

There have been several additions to the school over the last 150-plus years, most notably, the late 1940s Lower School buildings and the 1950s Brutalist Christison (Dining) Hall and art blocks, both by architect Austin Vernon & Partners. With the College keen to stop piecemeal development and embed targets for net-zero carbon emission architecture, a competition for a strategic masterplan was launched by the school in 2011 and eventually won by John McAslan + Partners. Its proposals included the refurbishment of the listed main buildings and landscaping improvements.

Subsequently, the most significant new build has been the 2016 science block. The Laboratory, by Grimshaw Architects, houses 18 labs, three preparation rooms, a 240-seat auditorium, and the James Caird lifeboat, used to make one of the most famous open boat voyages in history when Shackleton attempted to rescue his stranded crew during his trans-Antarctic expedition.

It was within McAslan’s strategic masterplan framework, that alma-nac began working on the Lower School mini-masterplan in 2018. With a view to incorporate more architecture into their arts curriculum, the College asked alma-nac to hold an arts workshop and exhibition in the school’s redundant boiler house, the location of the former swimming pool. It left a good impression and was commissioned to carry out a feasibility study for the Lower School corner of the campus.

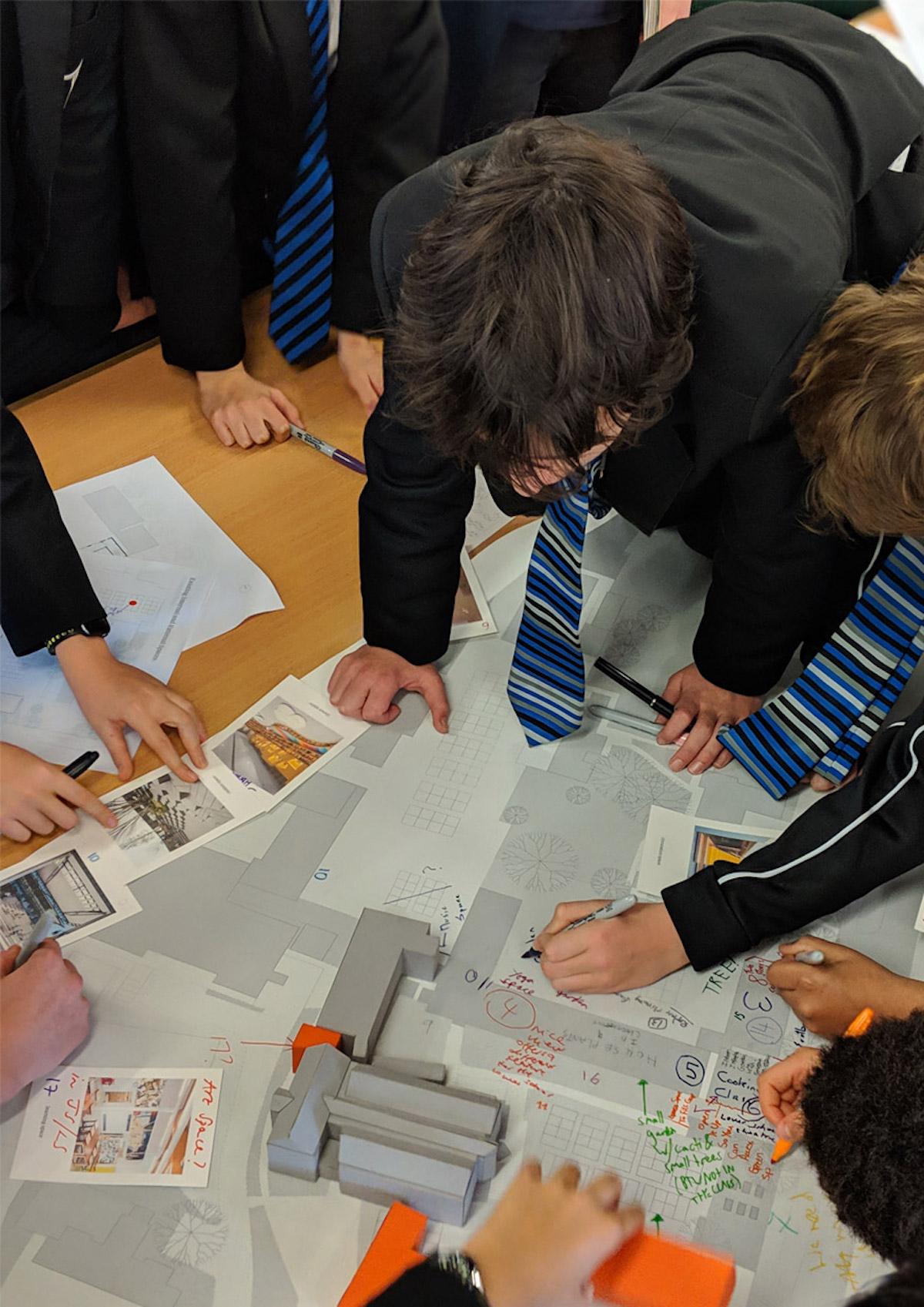

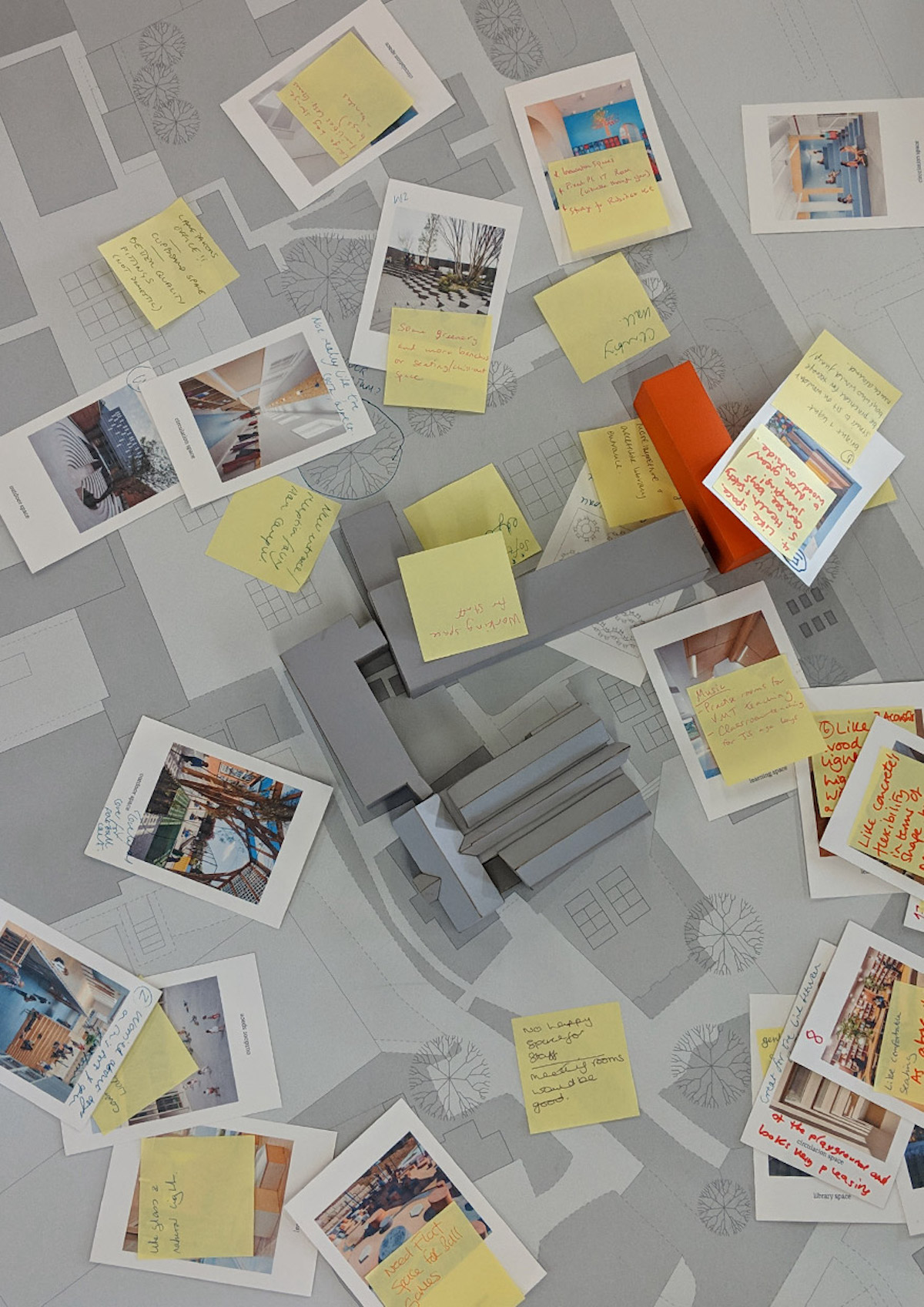

alma-nac undertook a series of workshops to engage pupils and staff in the design process.

The College’s brief was to upgrade the school’s existing building and to bring clarity to the Lower School, both architecturally, and in terms of spatial organisation, so the Lower and the Junior Schools could operate independently. The 11+ intake is the largest and most competitive entry point in the private secondary education sector, and so another key ambition was to provide a stronger presence and attractive identity through its built form and discrete facilities.

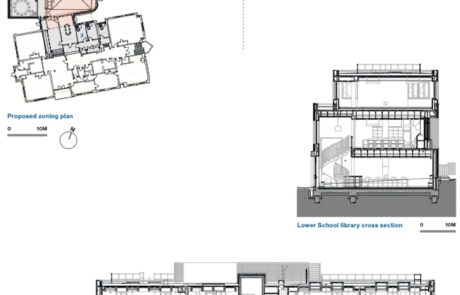

Meeting this brief will involve four interventions in two phases. Phase 1, the Raymond Chandler Library, replaces a fatigued row of single-storey portacabins and two new classrooms. The second phase will upgrade the Austin Vernon & Partners building, creating a new arts wing for the Junior and Lower Schools for music, art, and design and technology, and a distinct assembly hall for the Junior School.

The Raymond Chandler Library is arranged over three floors and connects to the corridors of the existing Lower School building on two levels with a new core. Importantly, this will provide step-free access to the upper floor classrooms for the first time.

The ground floor contains most of the library’s books, educational games and computing facilities. The ceiling is lined with timber slats which match the balustrading to the upper level and the built-in bookshelves and benches around the perimeter. The loose furniture, such as seats and mobile shelving, is deep turquoise in colour and, along with the expansive white walls, gives an age-appropriate, and more informal and contemporary feel to the space, when compared to the Middle and Upper School’s historic wood-panelled Wodehouse Library.

A double-height atrium unites the two library floors, creating a welcoming reception to the future campus, and actively engaging years 7 and 8 with the central role of library research in education and in life.

A spiral staircase links the entrance level to the first floor which, due to its open connection to the double-height ground floor space, feels more like a mezzanine or gallery than a self-contained level. The sculptural staircase harks back to the historic use of similar feature staircases within ‘grand libraries’. The staircase will eventually provide a ‘full stop’ to the eastern end of the U-shaped double-height circulatory spine to the Lower School, once both phases are complete. Framed by large-format windows on each side, it’s also a playful moment, and is a welcome departure from the angular nature of the rest of the building.

The upper floor accommodates more books, and lounge-style seating is arranged domestically to look out over the College’s athletics track and sports centre through further generous glazed openings. However, the main use of the space is as a flexible seminar room. When I visited, tables were laid out in a classroom arrangement with full-width rows facing a whiteboard at one end. But the room could successfully accommodate a range of other less traditional configurations.

The stars of the show here are the ziggurat carrel-style workstations, which line the eastern wall and face northeast towards the playing fields. alma-nac advised that they should be orientated to avoid glare, provide diffuse light and minimise solar gain. It’s easy to imagine these as popular spots and bagsied at lunchtimes and after school.

The second and uppermost floor contains three well-equipped computing rooms: one dedicated to robotics, the other two for each of the Junior and Lower Schools. These rooms are accessed via a new, wide square staircase sized to accommodate the flow of 12 forms of pupils moving between lessons. The organisation is efficient and effective for a building of this size.

The library’s extended opening hours encourage children to use the space before and after school for homework and independent learning in an environment that provides direct physical and visual connections to the wider campus.

Working alongside engineer Max Fordham, alma-nac has designed the building to Passivhaus principles and to be operationally net zero carbon, in line with the College’s net zero strategy (2050). The building is compact, triple-glazed, and well insulated, with good airtightness (2.22m3/h @ 50Pa), ensuring it is efficient to heat during the winter and easy to keep cool in summer. Working to Passivhaus was a steep learning curve, both for the design team in terms of ensuring thermal and airtightness continuity in the detailing; and for the main contractor, Life Build, to achieve on site.

Ample fenestration provides good daylight and enables natural cross ventilation via vents controlled by the Building Management System – helping to minimise energy consumption, provide thermal comfort, and contributing to the building’s BREEAM Excellent rating.

Post occupancy evaluation has been carried out after one year of academic use, and the College is processing the data. Staff and the facilities management team are still learning how best to use the building’s systems most effectively, with the energy use index (EUI) recorded higher than the design target of 65 kWh/m³.

A new, wide square staircase has been sized to accommodate the flow of 12 forms of pupils moving between lessons.

What is evident is that the building, and particularly the main library space, is used well, and in different ways depending on the time of day. The Raymond Chandler has become more of a common room, with students dropping in informally before and after school and at lunchtimes, whilst the number of books borrowed has doubled since it opened. The triumph of the new building is that boys are provided with fluid access to resources and books, but in a controlled and relaxed atmosphere, supported by nurturing librarians. Had this space been here when I arrived at Dulwich as an 11-year-old and one of 1,800 pupils, I can imagine I might have spent a lot of time here and maybe even read more books.

alma-nac engaged the estate team, teaching staff, pupils and librarians in the design process, ensuring all were on board with the sustainability goals. Through a series of ‘Baupiloten method’ workshops held during RIBA Stage 2, sessions were not only used to inform design but were a tool for teaching young pupils about buildings more broadly. Postcards with images depicting inspirational outdoor areas, circulation, library and learning spaces, sparked discussions about what stakeholders would like to see in their new building. It was in these sessions that alma-nac discovered that staff, students and librarians were adamant the main library area should be on the ground floor to facilitate access and provide a more direct connection to outside space, where previously it had been planned on the upper floor.

Left: Ziggurat carrel-style workstations line the east-facing wall of the upper floor, oriented to avoid glare, provide diffuse light and minimise solar gain. Right: Full-height glazed panels at the north corner of the upper library floor provide views over the College’s athletics track.

Externally, the building has a bold and confident external face. Of the collection of the school’s buildings along College Road, the Raymond Chandler sits closest to the pavement line, with an unapologetically contemporary external treatment, which responds to the uses beyond.

Initially conceived by alma-nac in redder tones in response to the Barry buildings and the adjacent interwar boarding houses, there was a desire from the College for the building to feel more current and reference the 1960s Christison Hall. The use of buff-toned brick is the clichéd default of ‘new London vernacular’ residential architecture, but feels successful in this context, echoing the Grimshaw science block, whilst still picking up creamy hues in the 1869 Palladian-style original winged block.

The top floor of the three-storey building is faced in a tightly scalloped 15mm thick glass reinforced concrete (GRC) cladding matching the tone of the brick and successfully breaking down the scale of the building, improving its proportions in elevation.

The façades are an informal, lively play of light and shadow. The deep reveals and thin window frames give a sense of quality and solidity. On the College Road façade, the ziggurat carrels are pronounced externally with sharp, angular detailing, creating an eye-catching centrepiece. The shadow play extends to the openings within the GRC top, which are tall and slender, picking up the narrow module, whilst the projecting brick detail is used to express the core on both main façades of the building.

The three-storey building replaces a single-level portacabin in use since 1998 with two open and airy library floors united by a double-height atrium. A third level, set back from the main frontage and clad in scalloped precast panels, provides ICT learning spaces and a robotics suite.

Large openings on ground floor offer views out of the library and animate the façade, permitting the public to see into the building while it is in use – a generous, and unusual move in school buildings. Externally, the building strikes a successful balance of informality and visual interest within the heritage context of the College.

Overall, the Raymond Chandler Library deftly achieves the brief. As a gateway to the Lower School from College Road, it provides the presence sought by the College and will be a calling card for prospective pupils and parents alike. Aesthetically, the combination of masonry and GRC feels robust, and the façade design should have enough character and rigour to endure without feeling dated.

Spaces are already well-used, and the building has improved life for the fortunate pupils who attend the Lower School, providing a bright new energy- efficient facility and universal access, whilst solving the classroom conundrum. The next phase will continue to unlock the circulation and create the additional required teaching spaces.

The challenge to the College will be to continue to build out the second phase of alma-nac’s Lower School mini masterplan – which will be more intricate – with the same high quality, enthusiasm and conviction as the shiny new Raymond Chandler Library.

Credits

Client

Dulwich College

Architect

alma-nac

MEP engineer and

net zero carbon consultant

Max Fordham

Structural engineer

Engineers HRW

Project manager/QS

Quantem Consulting

Landscape consultant

BD Landscape

Main contractor

Life Build Solutions

Energy assessor / BREEAM

Sustainable Construction Services