Masterplanned by Allford Hall Monaghan Morris, the redevelopment of a corner of London’s Spitalfields combines restored and reworked historic structures with new buildings by Stanton Williams, Morris+Company, DSDHA and AHMM. Chris Dyson assesses the results of a decade-and-a-half of controversy, collaboration, creativity and change.

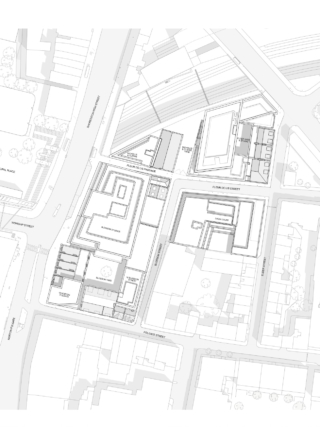

British Land’s redevelopment of Norton Folgate, a historic site between the City of London and Shoreditch, within Spitalfields’ Elder Street Conservation Area, has faced its share of opposition. But what now replaces the former warehouses is considered, of its time, and offers some interesting lessons in collaboration and renewal. Masterplanned by Allford Hall Monaghan Morris, the redevelopment comprises six buildings: three by AHMM, the others by Stanton Williams, Morris+Company, and DSDHA.

I have watched this corner of Spitalfields evolve and know the site well. I’m a local resident, as well as having my own studio here, in a former pub. We settled in the neighbourhood with our fledgling family some 30 years ago, and I used to buy building materials to renovate my old house on Fournier Street from the ironmongers, Nicholls & Clarke, in one of these old warehouses – an amazing warren of spaces that you’d go into and come out half an hour later with a box of screws.

There’s something about this area that has attracted architects and creative types over the decades. Part of its appeal is the character lent by its narrow alleys and shortcuts between big-boned warehouses, and its tension between history and change. Land has always had a productive value here. The new development replaces Victorian industry, which in turn replaced the Georgian finery of Elder Street and beyond; each generation shaping the place for its own needs.

And so, I welcomed the chance to talk to Paul Monaghan, AHMM’s Executive Director and Head of Studio, about the project, now that the wraps are finally off and the spaces are opening up. There has been much discussion around the height of these new buildings, but, as a resident, the greatest impact will be felt at ground level. My interest has been in the quality of the street, which I was keen to discover. It has been reassuring to see this managed well, with thought given at every turn to ground floor uses – something unusual for many commercial developments.

Site photographs taken in 2014 before work began.

Slow architecture

Paul explains how the project came about. British Land bid for the site, which was owned by the City of London. At that point AHMM had not done much with British Land other than a small fitness gym, but had been talking to them for many years about collaborating on larger projects. Fourteen years ago, the practice carried out capacity studies for the site with DP9, and established the neighbourhood plan and loose footprints of the designs. From appointment, the project was then a lengthy process, as the design team responded to local concerns; the Covid-19 pandemic; post-Grenfell changes to Building Control and the need for two stairs; then post-pandemic shifts in office demand. The result is a kind of ‘slow architecture’ that has been allowed to evolve from its place.

The plan was to provide a variety of office spaces, small and large, and to continue a long-established pattern of development going back to the 1700s. As Paul explains, “The big idea, which I felt from day one, was to have different architects working on it. I didn’t want it to feel like a homogenous scheme, but that it had different characters, with different styles of architecture. So that maybe, in 20 years’ time, you wouldn’t imagine it had been built in one go.” This has been delivered in a tapestry of material richness that retains the party wall nature of the existing buildings, as renovation and retrofit inventively fashioned from the old into the new.

A few surprises provide delight: DSDHA’s bay windows in the internal courtyard off Bishopsgate give flashes of opulence, and Morris+Company has triumphantly marked the corner of Folgate Street and Norton Folgate with its trademark over-scaled ‘skwinked’ window reveal – a gesture I think the Victorians would have been happy with. Elsewhere, minimal Modernism is exercised with care and panache by AHMM and Stanton Williams, whose courtyard detailing off the Elder Street entrance is thoughtful and appropriate.

View looking south along Shoreditch High Street towards Norton Folgate. Nicholls & Clarke and Blossom Yard, both by AHMM, are visible on the left.

Multi-studio collaboration

Paul reflects on how bringing together these studios a decade-and-a-half ago encapsulated a particular period in architecture. “Joe [Morris] was just getting going then. He’d done some work where he played with existing buildings that I thought was really inventive. DSDHA…we had enjoyed the way they collaborated; they always had some sort of narrative for a project picked up from the history of the site. Stanton Williams’ work I had always admired too; they have a distinctive style.”

Each architect team was encouraged to work in an original manner, avoiding tokenistic façade retention, yet keeping structures where feasible. The only rule was that they were all brick buildings, although not necessarily the same colour – an unusual decision for the creeping fringe of the City. Apart from that, he says, they “wanted everyone to be themselves.”

Paul describes it as more infill scheme than masterplan, an approach that’s more common in AHMM’s later projects, but was not the case then. British Land are sophisticated developers and took this strategy in their stride, and it shows. It feels like a development without ego, as the various architects worked collaboratively to make a great whole. The same team of architects was appointed within the framework of the AHMM neighbourhood plan all the way through planning to the final build.

During the construction stages, novation of the contract to the individual architects enabled the individual style to be maintained down to the handrails and window details. There were no ‘delivery architects’ here, but a collaborative approach that helped them get through what was at times a tough planning process. The local authority and Heritage England had internally approved all the details. However, the planning committee refused the project against the officer’s recommendation. It went to the then- Mayor, Boris Johnson, to decide and he found in their favour, with the caveat that one warehouse corner be kept.

The largest of the new courtyards showing, from left to right, DSDHA’s 16 Blossom Street, Morris+Company’s 15 Norton Folgate and AHMM’s Blossom Yard & Studios.

A series of Spitalfields ‘yards’

The public realm, designed by EAST, draws on the essential character of Spitalfields. It uses cobbled stones and granite curbs, carefully re-laid and polished to ensure DDA compliance. Local resident and historian Dan Cruickshank even had a hand in ensuring the quality of the cobbles’ installation. Of EAST’s involvement Paul says, “They’re really granular in the way they look at things – no big corporate gestures. I wanted the landscape to feel as though it had always been there.”

New garden courtyards provide access to the offices, an idea Paul describes as “quite radical, completely changing the character.” The largest forms the entrance to AHMM’s Blossom Yard & Studios, the office scheme at the heart of the development, which obscures its scale by stepping up asymmetrically along Bishopsgate. Ceramic highlights reference the old Nicholls & Clarke builders’ merchants.

DSDHA

This public space also anchors the renovation of a 1904 Arts and Crafts building and a new warehouse-style office on Blossom Street by DSDHA. There is a civic quality to the courtyard that is generous and inviting; it gives the site permeability, but also reflects the more ad hoc, informal spaces of the pub that once stood there, The Water Poet. A good pub, in fact – and its fate was one of my first questions to David Hills, who led this part of the project.

The pub, it turns out, provided inspiration. The informality of its spaces, he explained, contributed to turning “a corporate working environment into something that locks into the wider area.” For example, fragments of glazed bricks found in the pub’s yard led to the use of large sky-blue tiles. Gold bay windows reflect light and add sparkle. I asked about their articulated fins, and David explained their need to “make sure there was something very precise coming into those elevations” that was “deliberately other.”

“We were keen to work with the ambiguity of the Huguenot houses,” he explained. “Keeping the scale of those three elevations on the back captures that memory, that this is three buildings. You don’t lose that sense of reinterpreting a domestic scale.” Internally, party walls and chimneys are retained, and brickwork exposed to emphasise this character.

The variety of office spaces in the masterplan is a deliberate commercial move. At Exchange Square, DSDHA discovered that their client was able to generate higher rents for the areas around the new landscape. It seems the sign of corporate success is no longer the corner office, but a space of character in a unique City location: these features add a great deal to the commercial proposition. This principle was anticipated ahead of its time in the early planning of Norton Folgate.

For DSDHA, it was important to keep the corner with its strong chimney and characterful façade. But while the restoration was finely detailed, the warehouse was “deliberately mute and dark. We didn’t want anything that was going to draw attention to itself on Blossom Street.” The challenge from the outset was to retain different identities, as the scale in some places was so small. However, maintaining enough attention to detail for each element was the key that this multi-studio approach to the masterplan unlocked.

On this point, David recognised there were some challenges. The DSDHA commission on its own would ordinarily have been delivered more quickly than as part of a larger building contract. Still, he explained, “having a different architect work on each made it absolutely their focus.” And the teamwork gave opportunities for greater flexibility in “working outside and inside the red line.” DSDHA’s basement, for example, navigates a scheduled ancient monument under the site and provides cycling amenities for the Morris+Company building next door.

Morris+Company

15 Norton Folgate combines the careful restoration of a Georgian terrace on Norton Folgate with a new red brick building that turns the corner onto Folgate Street.

15 Norton Folgate by Morris+Company is, as they describe it, “a community of small, flexible workplaces driven by the principles of low-energy, long-life and loose-fit.” Again, the commission combined old and new; the refurbishment of a Georgian terrace on Norton Folgate with a new building to turn the corner of Folgate Street. “We had the smallest new build, but the one that caused the most consternation, because it was a gateway corner into Spitalfields,” explains Joe Morris, as he and Associate, Elena Lledo talk me through their decade. We discuss the foresight of the project’s early vision in looking at what the market might be – and then “designing for it, a decade before handing the key over.”

Elena describes their evidence-based approach to the tapestry of existing brick and new pointing that gives the row its distinctive texture: “We went around with a piece of chalk. We would mark up in blue the areas that required repair, usually repointing, and in red the areas that needed replacing. It was like acupuncture.” Internally, the offices retain a mix of traditional domestic and contemporary industrial details, with brick chimney breasts against exposed services.

On the collaborative aspect, Joe describes the project as going through eras. During its lifespan came the Covid-19 pandemic, and they found great support in the fortnightly catchups with the wider team. It was extremely collaborative at a conceptual level. He describes it as almost a “super team”, where the studio boundaries didn’t feel quite so rigid. “At the same time”, he adds, “we’re working with extremely good, gifted people, so you’re on your best game. You don’t want to be the weaker one.”

The emergence of this new quarter over the years has tracked the growth and evolution of each practice. Today, Morris+Company has an extensive portfolio of large-scale schemes and offices in London and Copenhagen. However, “back then, we were just an eight-year-old practice, terrified at being in a room with Paul Williams and Paul Monaghan, Deborah Saunt… We had to puff our chests out a bit, being the minnows.” He describes Paul Williams at that time as something of a wise sage – and so I felt it appropriate to consult the sage’s wisdom for my next conversation.

Stanton Williams

Looking west along Fleur de Lis Street with Stanton Williams’ Elder Yard & Studios visible on the right. The shift in scale from historic Spitalfields is handled by stepping and folding the new buildings away form conserved heritage.

Stanton Williams designed Elder Yard & Studios, as British Land puts it, “contemporary office space with an old soul.” The building combines an original Victorian warehouse with a new ten-storey building. There is another dimension to Paul Williams’ solicitude for Spitalfields, as he used to be one of my neighbours on Princelet Street. We have both picked up supplies for our home renovations from the old Nicholls & Clarke.

Here, the organising principle is the ground plane: routes are driven through into courtyards, based on interpretations of old maps of the site. We discussed at length the decision to keep the corner building onto Commercial Street: a former shop unit, which “looks at first glance odd,” he notes, however, the overall assembly works. At ground floor, the older buildings frame a new entrance to another yard in the middle of the block, signalled by black aluminium, which is carried through to the street from the interior courtyard.

In this part of Norton Folgate, there is the more pronounced shift from Spitalfields’ domestic scale to that of the City office buildings. Not an easy shift to make in such a confined space, but one well-handled here by stepping and folding elevations away from the conserved heritage. Maintaining the warehouses on Blossom Street and Elder Street has created a datum of scale and character, above which the new is not so prominent, yet still unapologetically modern and bold.

In some cases, there was no way to maintain the spaces behind the façade, but it was necessary to hold onto these artifacts of history while making the new buildings viable. Seen from the outside, the brick elevations are ‘hole in wall’. A light brick avoids the buildings appearing overbearing and reflects the light. The new draws its proportions from the existing, save for the ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ moment at the centre, where all-glass and aluminium elevations frame the courtyard.

View from Shoreditch High Street. The light brick stops the new-build element from being overbearing, and reflects the light.

AHMM

The final piece of the composition, AHMM’s Nicholls & Clarke, slots into the triangular corner site. Paul Monaghan calls it a “pencil-like marker on Bishopsgate.” Its glazing echoes the City and Stanton Williams’ scheme; it borrows colours from the other buildings and retains the brick warehouse façade. It’s interesting to reflect on whether the City brings its character to Spitalfields, or – perhaps, as we see here – the influence extends the other way.

Taken altogether, this development aligns with the goals of the ‘better cities’ movement, bringing together individual buildings and people – placemaking with unlikely bedfellows, now sitting at the same table. Against this backdrop of intense collaboration, what of the early battle? Of course, this is a place that I have a deeply personal, as much as professional, connection with. Change can sometimes be daunting. But necessary, as I also believe in the precious commodity that is human creativity. And in a civilised world with limited talents and resources, I believe the planning process should support those delivering quality, particularly when they are so clearly working in a sympathetic manner to revive part of a neighbourhood.

Future projects, such as The Goodsyard, damaged by a fire in 1965 and since left abandoned, and the Truman Brewery, bombed by the Luftwaffe in the Second World War, are all in process. We’re designing buildings within both schemes. These projects similarly bring together teams from different firms, each with their own approach and style, to bring out and celebrate a richness and diversity the East End has always been known for. As Joe Morris said, “If you go back a few more years, practices working together just didn’t exist. But with design review panels, peer review, CABE…the way architects engage is changing.” And this is necessary because, “it’s not just architecture as an art, it’s about a social and commercial paradigm.”

As architects, we are used to collaboration with broad disciplinary teams. I think the opportunity here, at a neighbourhood and city scale, is for developers to work together to demonstrate similarly engaging examples of streets and squares, alleyways and open space. Certainly, these projects represent slow architecture. Considered and engaging its community – and all the better for that.

Credits

Client

British Land

Masterplanner

Allford Hall Monaghan Morris

Architects

Allford Hall Monaghan Morris, Stanton Williams, Morris+Company, DSDHA

Public realm

East

Main contractor

Skanska

Enabling works contractor

Cantillon

Project manager

M3 Consulting

Structural/civil engineer

AKT II

Cost consultant

Turner & Townsend alinea

MEP engineer

Arup

Planning consultant

DP9

Facade consultant

Eckersley O’Callaghan

Sustainability consultant

Atelier Ten

Access consultant

Hilson Moran

Archaeology

MOLA

Fire engineer

Kiwa

Acoustic consultant

Sandy Brown

Lighting designer

Studio Fractal

Security consultant

QCIC

Health & Safety advisor

Arcadis

Employer’s representative

Rex Procter & Partners