Spanning the gorge at Tintagel with a new footbridge is a bold move handled with exemplary sensitivity by Ney & Partners and William Matthews Associates, finds Ezra Groskin

The north Cornish coast is undeniably beautiful, the jagged edge where rolling countryside plunges into the sea. Nothing is gentle about this place; living here has always required equal measures of endurance and resilience. It’s no wonder the Cornish are a proud people rooted in tradition, their perseverance rewarded with dramatic scenery and a deep connection to the land.

The mystique of the coast is very present at Tintagel where the land juts out into the sea, sheltering coves and caves on either side. This area inspired generations of storytellers and was immortalised in the twelfth century when Geoffrey of Monmouth chose it as the setting for the conception of King Arthur in his ‘History of the Kings of Britain’. The popular tale has drawn countless visitors and inspired a number of phases of building at Tintagel. Hundreds of thousands of people are now drawn annually, and who can blame them? After all, this is the stuff of legends.

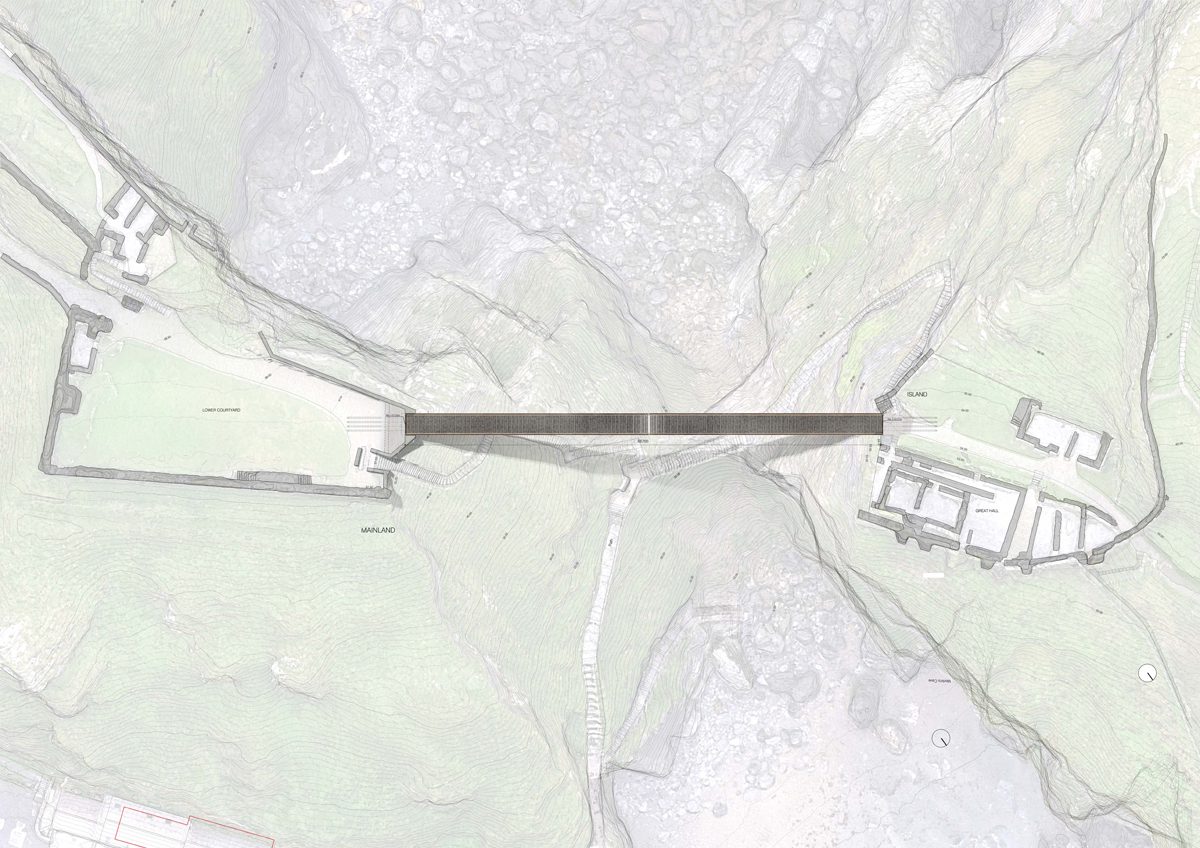

Architect William Matthews Associates and Brussels-based engineer Ney & Partners were selected from 137 entries to the international competition for the bridge. “Our proposal was based on a simple concept”, says WMA. “To recreate the link that once existed and fill the current void. Instead of introducing a third element that spans from side to side, we proposed two independent cantilevers that reach out and touch, almost, in the middle”.

In 2015 English Heritage caught the attention of the entire bridge design community when it launched a competition to design a footbridge that would reconnect the Tintagel promontory to the headland. Historically a narrow land bridge formed this connection, upon which was built a perfectly secure stronghold named Din Tagell – ‘The Fortress of the Narrow Entrance’. Ironically the easily defended land bridge proved to be the fortress’ downfall as it eroded into the sea 500 years ago, leaving a relatively inaccessible ‘island’.

The decision to reinstate this bridge was incredibly ambitious, and the design competition had the ingredients of greatness: a dramatic site, a public location, a straightforward A-to-B spanning function, a reasonable construction budget, and an enlightened client. Seizing the opportunity of a generation, the six shortlisted teams went all-in, producing inspiring, boundary-challenging designs that demonstrated varying degrees of understated elegance. They represented a gradual shift in bridge design, with appropriateness now valued over flamboyance and modesty over ego.

Aerial view of the bridge deck. The coastal site, associated with the legend of King Arthur, is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and protected by Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, Special Area of Conservation, Site of Special Scientific Interest, Marine Conservation Zone and Heritage Coast designations (ph: David Levene).

The Belgian-British team of engineer Ney & Partners with architect William Matthews Associates presented the winning design, a combination of elegance and ambition. It also demonstrated the experience and technical knowledge required to deliver its vision.

In the years following the competition, EH faced significant political challenges. Building within a conservative context is hard, building on a renowned archaeological site is almost unthinkable. The design team also had to overcome technical challenges to ensure the bridge’s stability: extreme slenderness relies heavily on stable rock at either end. I praise EH for investing in ideas and talent, as well as having the foresight and courage to begin this project and the tenacity to see it through.

Tintagel Castle is a refreshingly simple attraction. A narrow path with subtle signage and minimal boundaries are the only interventions in an otherwise unspoilt, richly historical landscape. Visitors are encouraged to wander and use their imaginations to unpeel the layers of time. While the bulk of the stone ruins are attributed to Richard, Earl of Cornwall’s thirteenth-century building spree, he would have built upon the foundations of previous generations dating back to the original fifth-century trading settlement.

Despite the significance of these ancient ruins, very few barriers prevent visitors from touching or climbing upon them. Alongside this simplicity, the new bridge has made a significant impact. Not only does it transport visitors over a void previously navigated only via precarious steps, it also anchors the wider experience, serving as the hub in a figure-of-eight circuit. Furthermore, the eye-catching structure acts as a visual point of reference, seen stretching between the opposing rock faces from a wide range of viewpoints.

The surface of the bridge deck is formed of 40,000 hand-cut Delabole slate tiles, from a quarry three miles from Tintagel. They are laid on edge in steel trays and interspersed with white quartzite tiles – an allusion to the lines of quartz found in local slate. The bridge is secured to reinforced concrete abutment blocks by 15-metre-long Dywidag rock anchors. The Telford bracing is in electropolished stainless Duplex steel. “Contrasting weathered and non-weathered steel allows sunlight to play on the structure but also gives it an ephemeral quality, allowing the bridge to harmonise with the coastal landscape”, says WMA. The 40mm gap between the two halves of the bridge is matched by a gap in the English green oak handrail. “Visually the link highlights the void through the absence of material in the middle of the crossing”, says WMA.

I was fortunate to visit on a clear yet windy day. Crossing the bridge was a dramatic experience. Tall stone walls surrounding the gatehouse courtyard funnelled me towards the structure, which I first saw only moments before occupying it. The instant I left the protection of these walls and stepped onto the bridge I was faced with the full force of the sea breeze funnelling through the chasm.

The bridge dares you to cross. Those brave enough to pause at midspan are appropriately rewarded. Stunning views up and down the coast are amplified by the feeling of flying. Unlike many footbridges that rise up to a crown at midspan, this one distinctly dips down towards the middle, which is especially visible when approaching from the south. Before visiting I was sceptical of this decision, but I now appreciate its contribution to the impression that the footway is ‘slung’ between the two rock formations. It’s an appropriate gesture of subservience to the elevated ruins at either end. The only shortcoming, which is minor, is the abruptness of this dip at midspan, which is foreshortened in oblique views. However when seen from afar the bridge’s splayed ends and narrow middle make it look as though it is stretching (rather than spanning) from the mainland to the island, which is slowly receding into the sea.

In terms of materials and details, Ney & Partners and William Matthew Associates have excelled. The exquisitely crafted stainless steel parapets are reassuringly stable while reading as a taut lattice simply stretched from end to end. Equally successful is the slate walking surface itself. Having feared that slate was only proposed as a token ‘contextual’ gesture to score competition points, I was stunned by both its beauty and functionality. As is evident throughout the site, slates on edge offer incredibly good traction. On the bridge this raises your awareness of the surface below you, keeping you alert (in a good way). The sound individual slates make as they rattle loosely in their stainless steel trays furthers the feeling that you’re traversing an art installation rather than a bridge. This playfulness combined with an extreme level of care fittingly captures an ancient spirit of craft.

“The structure, 4.5 metres high where it springs from the rock face, tapers to a thickness of 170mm in the centre, with a clear joint between the mainland and island halves. The narrow gap represents the transition between the mainland and the island, the present and the past, the known and the unknown, reality and legend.” The bridge is 57 metres above sea level. Its two 33-metre-long cantilevered halves were installed in 12 prefabricated five-tonne sections, lifted by a cable crane spanning the valley. Helicopters were also used to deliver materials.

As a bridge designer, I’m a long-time admirer of Laurent Ney and his studio’s inspiring portfolio of built work. I’ve often assumed that he plays by his own rules, making things stand up where others wouldn’t dare. The most notable structural feature of the new bridge at Tintagel is that despite its arched appearance in elevation, it is actually two independent cantilevers that ‘meet’ in the middle. At the competition stage, emphasis was placed on a gap at midspan. It served as an easily grasped metaphor for the threshold between “mainland and island, present and past, history and fantasy”. While this rhetoric is cheerful, I suspect the gap was the result of a profound structural concept rather than a philosophical launching point.

In principle the structure is a clear response to its site: rather than resisting the wind, the bridge welcomes it, swaying like the branches of a tree. The result is an incredible form defined by void rather than mass. It is both slender and supple, two attributes contributing to the exhilarating crossing experience. In stark contrast to the heavy masonry remnants of Tintagel Castle and the various settlements strewn across the site, the new structure features a hierarchy of elements, clearly optimised to be as light as possible. The visual mass of each element relates to its structural function. The painted steel top chord at deck level is stitched to the curving bottom chord via a filigree of stainless steel bars. All joints have been carefully considered and executed, left visible as an insight into the construction method. The resulting composition has the delicacy of jewellery, inviting admiration from all angles.

Tintagel’s new bridge is already becoming the centrepiece of an awe-inspiring visitor experience. Its owners and makers have every right to be proud of their achievements. While some have questioned the impact additional visitors will have on the fragile site, I believe that English Heritage is fully capable of maintaining the balance between preservation and enjoyment. It understands the importance of inspiring future generations, who will in turn carry the mantle. They will be tasked with maintaining Tintagel’s winning formula: an exquisite landscape, a rich history and an amazing bridge to take you there.

Additional Images

Credits

Designers

Ney & Partners and William Matthews Associates

Design team

Laurent Ney, William Matthews, Matthieu Mallie, Bart Bois, Aline Roger, Ambra Chiesa

Structural and civil engineer

Ney & Partners

Geotechnical engineer

Ramboll

Cost consultant, contract administrator

Faithful & Gould

Planning consultant

CSJ Planning

Main contractor

American Bridge UK

Client

English Heritage

Steelwork subcontractor

Underhill Engineering

Slate deck

Delabole Slate

Rock anchors

Dywidag